Can stars form around black holes?

The Milky Way's central black hole is surrounded by stars. Did they migrate into the proximity of our void, or were they born there?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In the 1930s, when physicist and engineer Karl Jansky pointed his radio antenna towards the center of our galaxy, he detected a continual source of radio waves. After some analysis, scientists realized these radio waves were being emitted by something vastly further from our planet than the sun — but oddly enough, they were comparable in energy to the waves we do receive from the sun.

With this information, they began to suspect something truly powerful must be lurking in the center of the Milky Way.

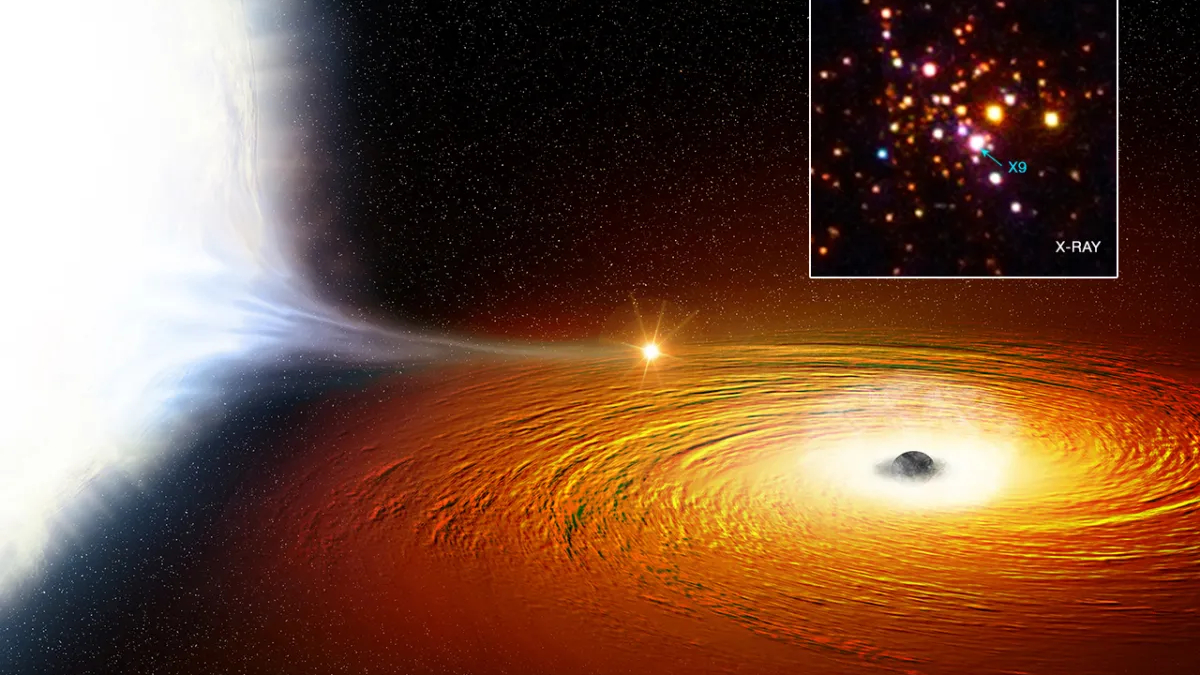

Astronomers later came to realize that the source of these mysterious radio waves was none other than a supermassive black hole more than a million times massive than our own sun We now call it Sagittarius A*. Commonly abbreviated to Sgr A*, the enormous object basically serves as a gravitational anchor for the entire Milky Way. Since these early observations, astronomers have come to learn quite a bit about Sgr A*; because astronomers can actually observe it, the black hole provides our best chance at answering an intriguing question — is star formation possible around black holes?

Related: Swirling gas helps scientists nail down Milky Way's supermassive black hole mass

Sgr A* is surrounded by a bunch of molecular clouds — interstellar hazes in which you might see a star or two pop into existence. However, astronomers have thought that the proximity of these clouds to the black hole could disrupt any possible stellar nurseries cranking on within, as extreme tidal and electromagnetic forces are believed to destabilize the pockets of gas which typically accumulate to form stars.

"The combination of a low density medium and strong tidal forces by the [supermassive black hole] make it difficult for stars to form in the 'standard' way, that is from the collapse of dense gas clouds. They would be torn apart before being able to collapse," astrophysicist Rosalba Perna from Stony Brook University in New York told Space.com

More recent observations, however, have pointed to the possibility that star formation might be occurring a lot closer to Sgr A* than we initially realized.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers, for some time, have been observing stars in the vicinity of Sgr A*, but have explained their presence away as possibly due to them migrating towards the black hole after originally forming in distant clusters. The problem with this explanation, though, is that a lot of these newly discovered stars appear too young to have been able to form far away then travel across space to get to Sgr A*.

Young Stars Spotted Close to Sgr A*

Led by Florian Peißker, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cologne’s Institute of Astrophysics, the team of astronomers identified the young stellar object X3a.

"It turns out that there is a region at a distance of a few light years from the black hole which fulfills the conditions for star formation. This region, a ring of gas and dust, is sufficiently cold and shielded against destructive radiation," Peißker explained in a statement.

Surrounding Sgr A*, and other supermassive black holes for that matter, is an accretion disk of gas and dust falling towards the black hole due to its immense gravitational pull. The particular disk that envelops Sgr A* extends out between 5 and 30 light-years from the event horizon of the black hole.

The team believes X3a may have formed in a gaseous envelope in the outer ring of the accretion disk surrounding Sgr A*. These clouds of gas could get large enough to collapse into themselves to form protostars.

Researchers have also speculated about other possible explanations for the presence of stars in close proximity to Sgr A*.

"The presence of young stars around black holes has made astrophysicists broaden their view of star formation, and various theories have been developed to explain them, such as formation in a disk resulting from the disruption of a molecular cloud, formation in a distant cluster followed by inward migration and shock compression triggered by a tidal disruption event," says Perna.

Perna recently authored a paper which suggested that tidal disruption events (TDEs) close to black holes could create the right conditions for stars to form. TDEs are events where gravitational instabilities can be introduced into the accretion disk of black hole, an example could be a star falling towards a black hole. These TDEs can interact with the accretion disk of a black hole in such a way that high densities of gas and dusk occur, which allow the collapse of dense clumps into young stars.

Perna explains that star formation around black holes is likely affected by the evolutionary stage of said black hole. When a black hole is "active", likely during its early phases when the galaxy that surrounds it is a chaotic place, it is surrounded by an extended accretion disk of gas and dust. This accretion disk can be fertile ground for star formation due to the accumulation of high densities of matter. However, now that the Milky Way is much older, things have settled down, and star formation around Sgr A* has likely slowed down from what it might have been in the distant past.

While black holes remain in the category of cosmological enigma, astronomers are learning more about how they interact with their surroundings to birth new stars and affect the evolution of their home galaxies.

Conor Feehly is a New Zealand-based science writer. He has earned a master's in science communication from the University of Otago, Dunedin. His writing has appeared in Cosmos Magazine, Discover Magazine and ScienceAlert. His writing largely covers topics relating to neuroscience and psychology, although he also enjoys writing about a number of scientific subjects ranging from astrophysics to archaeology.