Nowadays, when looking for a local weather forecast, most people will pull out their smartphones and check a few different websites or perhaps Facebook. Others may get their information from radio or television. Most newspapers provide a weather page including the forecast, augmented by a weather map and perhaps some almanac information containing the rising and setting times of the sun, moon and planets.

But if you were living 150 years ago, all of the above possibilities did not exist. Yes, the Old Farmer's Almanac was around back then with its long-range weather forecasts based on its famous "secret formula," but really — then, as now, those "tried-and-true" outlooks weren't really all that dependable.

No, if you were living in the mid-19th century or earlier, you probably learned to make your own weather forecasts by being aware of your surrounding environment. Unlike most who live in our modern world, people who lived back then were far more "weather wise."

Related: The Top Skywatching Events to Look for in 2019

Meteorological signs

For example, there is a famous axiom attributed to ancient mariners:

Red sky at night

Is the sailor's delight;

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Red sky in the morning

Sailors take warning.

This limerick probably came out of a biblical verse. In Matthew 16:2, Christ is quoted as saying: "When it is evening, ye say, It will be fair weather; for the sky is red. And in the morning, It will be foul weather today; for the sky is red and lowering."

And all this is not simple folklore!

That red sunset, for example, was a view of the sun that was attenuated through a dusty layer of haze approaching from the west. According to the Library of Congress, this indicates high-pressure, stable air. If a wet or moist air mass were approaching from the west, the sun shining through it would appear to be gray or even a mellow yellow, leading to yet another weather saying: "Last night the sun went pale to bed."

Another "old-time" weather observation noted when a large halo appeared to encircle the sun or moon — this indicated cirrus or ice-crystal clouds accompanying an approaching warm front, which within 18 to 24 hours will lead to rain (or in winter, snow). A sky filled with such webby cirrus clouds foretells just such an approaching weather disturbance.

Sailors were aware that a distant shoreline would appear to "loom up" closer when rain was less than a day away. Marine air is rich with salt haze from evaporation during good weather, but increasing atmospheric instability as a storm system approaches causes a mixing effect that clears away the salt haze and results in excellent visibility.

These and many other weather observations can be found in "Eric Sloan's Weather Book." First published in 1948 by Hawthorn/Dutton, it has gone through many reprintings. You can probably find a copy at most online book sellers. It is very readable and informative; as a broadcast meteorologist, I highly recommend it.

Ancient weather forecasting guide

There is, however, one weather portent that is not mentioned in Sloan's book. It has been known for over 2,000 years, but it deals with a celestial object that was well-known to ancient skywatchers.

To see it, we must turn our attention to a constellation that this week is high above the southern horizon during the mid-to-late evening hours. That constellation is Cancer, the Crab — the least conspicuous constellation of the zodiac. Indeed, if Cancer was not part of the zodiac it is doubtful if it would be considered important at all. In our sky, the Crab occupies an otherwise empty space between the heads of the Gemini twins and the sickle of Leo. Cancer is noteworthy, however, because it contains one of the brightest galactic star clusters — which actually goes by two different names.

Some astronomy texts speak of "Praesepe, the Manger," while others call it the "Beehive." A manger is defined as "a trough in which feed for donkeys is placed." The cluster was apparently first called Praesepe 20 centuries ago. In 130 B.C., Hipparchus called it a "Little Cloud," while Aratus, around 260 B.C., referred to it as a "Little Mist." A hazy patch of light to the naked eye, it becomes a large and beautiful scattered cluster of stars in binoculars. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) first resolved the cluster into stars in 1610. The cluster's relatively new moniker, "Beehive," seems to come from its appearance. An apocryphal story states that some anonymous person, upon seeing so many stars revealed in one of the first crude telescopes, exclaimed: "It looks just like a swarm of bees!" Hence, the reason for why some astronomy books call the cluster "Beehive," while others call it "Praesepe."

The Beehive was also used in ancient times as a weather indicator. Both Aratus and Pliny have said that the invisibility of this object in what otherwise might be considered a clear and starry sky forecasted the approach of a violent storm or served as an omen of coming rain or snow. The outermost fringes of an approaching weather disturbance consists of very thin/high cirriform clouds, which might otherwise not be noticed under a dark, moonless night sky. But such clouds are apparently just opaque enough to block out the light of the Beehive.

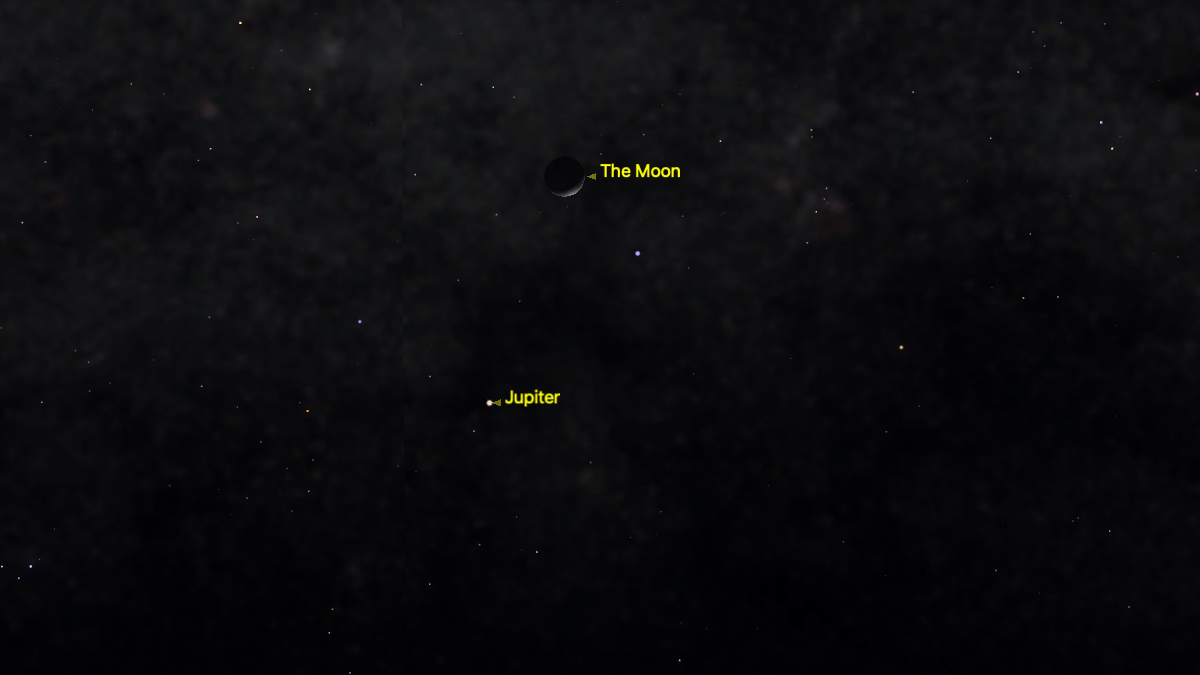

If you are fortunate to have access to a dark, non-light polluted night sky, you might want to test this out for yourself, although be advised that after Tuesday (March 12), the moon is going to pose a problem as it will reach first quarter the following night and in the nights thereafter it will draw closer to the Beehive while also getting progressively brighter; it will be sitting only a few degrees to the east of the Beehive on St. Patrick's Day. After March 22, the moon will be less of a hindrance, as it will be waning in brightness and rising progressively later each night.

- Best Night Sky Events of March (Stargazing Maps)

- Best Binoculars for Astronomy, Nature, Sports and Travel

- Constellations: The Zodiac Constellation Names

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's Lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.