Chandrayaan-3 vs. Luna-25: Are India and Russia racing to the moon's south pole?

These missions are more of a moon marathon than a lunar sprint.

It’s been touted as a race to the lunar south pole, but there's much more to India's and Russia’s moon shots than who lands first.

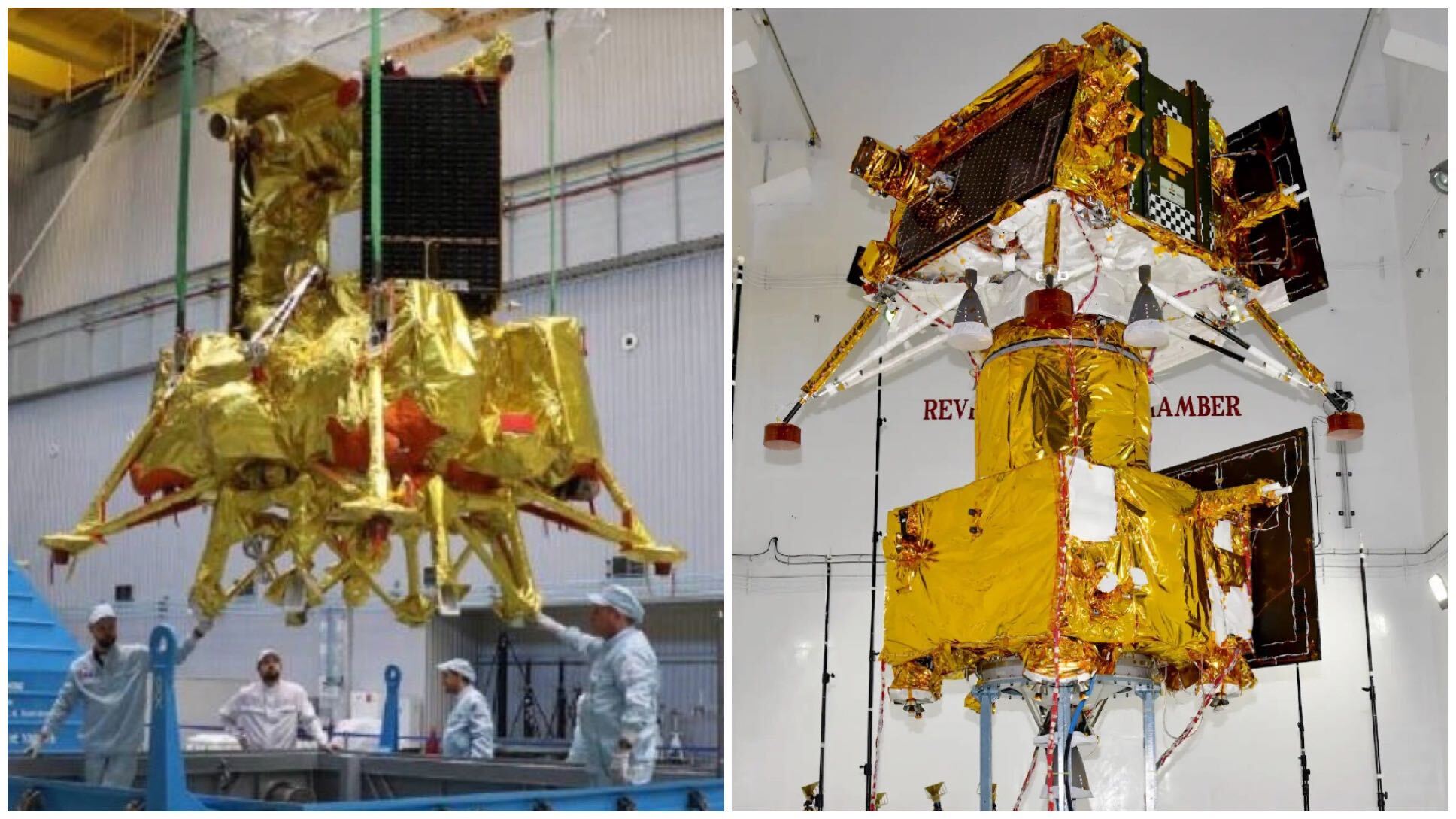

India's Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander launched on July 14 and entered lunar orbit on Aug. 5. It is currently lowering its orbit in preparation for a landing attempt that's expected to occur on Aug. 23.

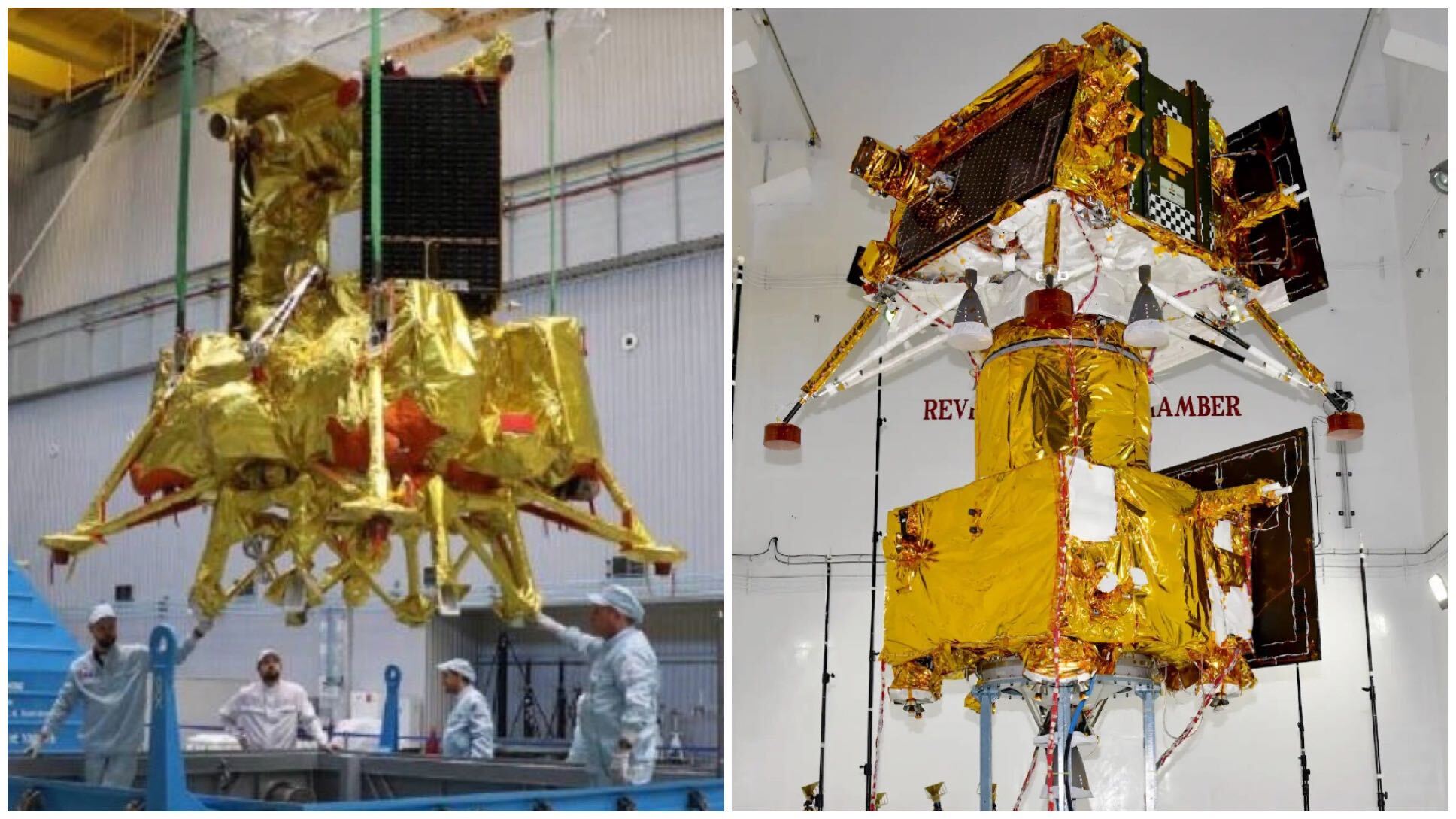

Meanwhile, Russia is making its first visit to the moon since 1976, when its Soviet-era sample return mission dubbed Luna-24 took place. Luna-25 launched on Aug. 10 and, having taken a more direct route to the moon, could make a landing attempt as soon as Aug. 21.

While the so-called race is intriguing, however, it is a bit of a non-starter with a debatable finish line and no discernable prize on the line. But, on the other hand, there are also important matters of prestige to consider, as well as implications for potential follow up missions and opportunities for international cooperation.

And, of course, there is quite a bit of science at stake.

Related: India's Chandrayaan-3 moon rover enters lunar orbit, snaps stunning photos (video)

Which will land first?

A key factor in when these spacecraft will land is the timing of the sun's trajectory. The sun must be rising over these probes' respective landing spots because sunlight will provide power for the spacecraft on the surface. Another factor has to do with when the probes' orbits will pass over the landing sites. Both Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 will be in polar lunar orbits, with the moon rotating below as they orbit above.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Chandrayaan-3 is targeting a landing site at 69.37˚S 32.35˚E. The sun will rise over this area early on Aug. 21 GMT, meaning lighting will be suitable for the solar-powered Vikram lander and Pragyan rover by the time it lands around 17:47 IST (1217 GMT, 08:17 a.m. EDT) on Aug. 23.

Meanwhile, Luna-25 is targeting the Boguslawsky crater at 72.9˚S 43.2˚E. As this region is farther east, the sun will rise earlier over this site (Aug. 20), meaning the partially solar-powered Luna-25 may be able to land earlier as well. It will, however, depend on the lunar orbit Luna-25 enters and Roscosmos' plan.

Vikram and Pragyan are solar powered and have a mission lifetime of one lunar daytime (around 14 Earth days), so landing early will be important to how much they can achieve in the time they have. Luna-25, however, comes packed with a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) which will supply heat and power needed to keep the lander working for at least a year, meaning a landing time early in the local lunar day may not be such a priority.

#WATCH | If everything goes normal then landing on the moon is expected on August 23rd at around 5.47pm IST, says ISRO chief S Somanath on #Chandrayaan3 pic.twitter.com/rcIk5HxZ8DJuly 14, 2023

Will they land successfully?

The moon is the center of renewed global interest and is being visited by a fleet of spacecraft from various countries. While the moon has welcomed robotic landers numerous times, only China has landed successfully so far this century (with the Chang'e 3, 4 and 5 missions). And, unlike those Chinese missions, India's and Russia's attempts are targeting the vicinity of the lunar south pole.

Though there is intrigue as to which craft will land first, whether they pull off a soft, safe landing or make a hard, mission-ending impact is the key question.

Russia has not landed on the moon since the Soviet days. The last Soviet mission was Luna 24, which launched 47 years ago. Russia's last interplanetary mission, Fobos-Grunt, which aimed to collect samples from Mars' moon Phobos, failed to get out of low Earth orbit in 2011. Luna-25 has been delayed for more than a decade. Engineers also needed to make changes to the landing navigation system late in the spacecraft's development .

As for India, the country is aiming to join the United States, the former Soviet Union and China as the only nations to perform a soft lunar landing. It would also be a tremendous feat for the country along with the Mangalyaan mission, which entered Mars' orbit in 2014 and ended its tenure in 2022 because it ran out of battery. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) says it has learned lessons from the failed landing attempt of the Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft in 2019.

Recent attempts at moon landings by Israeli and Japanese companies have not gone well, highlighting the challenges ahead.

Landing successfully therefore cannot be taken for granted for either mission, and both India's and Russia's endeavors will be watched keenly around the world.

Will they really land at the south pole?

Landing at the south pole is the focal point of international intrigue regarding possible presence of trapped water-ice which could be used for propellant or supplying lunar habitats with life-sustaining materials?

India and Russia aim to land further south than any previous lunar touchdown — 69 and 72 degrees south of the equator respectively. The sites are not considered truly polar, but that does not mean we won't be learning something new. Landing near the equator is also known to be favorable for a number of technical reasons including lighting, communications and easier-to-navigate terrain.

"Neither is a polar location, but rather high latitude locations," Clive Neal, a lunar exploration expert in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, told Space.com. "We have not really visited such southern high latitude locations before, so from a curiosity and science viewpoint, these landers will give data from new locations on the moon."

Both missions are chiefly aiming to test and demonstrate technology for future soft landings on the moon.

How do the spacecraft match up?

The landers have a similar mass, with Luna-25 weighing around 3,860 lbs (1,750 kg) at liftoff, with just over half of which is expected to be propellant. The Chandrayaan-3 Vikram lander meanwhile weighed 3,862 lbs (1,752 kg) including a 57 lbs (26 kgs) rover named Pragyan. Much of Vikram's mass is also propellant for landing.

Luna 25 carries eight science instruments, including the lunar manipulator complex (LMK) which is capable of excavating lunar regolith and the Neutron and gamma detector (ADRON-LR) geared to seeking water ice.

Vikram will meanwhile be looking to make the most of its (only) day in the sun. It carries four science payloads, one of which will insert a thermal probe into the lunar soil to a depth of around four inches (10 centimeters) and take temperature readings of the lunar regolith throughout the lunar day.

Pragyan will meanwhile carry the Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscope (LIBS) and the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) for lunar regolith studies. A retroreflector on Vikram will however be useful long after the lander ceases working. The retroreflector is designed to reflect a light directly back to a source, and is an upgraded version of those put on the moon by the Apollo missions and will be used to accurately measure the distance and variation in distances between the Earth and moon.

A notable aspect with these missions is that of international cooperation, which is usually a strong feature of space missions. Russia however has been largely isolated internationally since its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the country's ongoing occupation of Ukrainian territory That provoked the European Space Agency to cease its involvement in the Luna-25, -26 and -27 missions. It and also postponed the launch of the Rosalind Franklin rover from the ExoMars program, which aims to seek out traces of past or present life and will now launch no earlier than 2028.

For Luna-25, it meant ESA's PILOT-D navigation camera was no longer available to assist the landing attempt.

India’s mission, on the other hand, is being supported by ESA's "Estrack" network of deep space stations, helping to track, command and receive data from Chandrayaan-3. NASA is contributing the retroreflector for lunar laser ranging.

Impact on future missions?

Russia is planning on launching further Luna probes, including Luna-26 in 2027, Luna-27 a year later, and Luna-28 no earlier than 2030. It aims to play a big part in the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) rather than the US-led Artemis program.

India is planning a joint mission with Japan, named Lunar Polar Exploration mission (LUPEX), to launch later in the decade. The country has also signed up to the Artemis Accords.

How Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 fare with their landing attempts could have knock-on effects for future missions or even participation in wider programs. In a matter of days, we will find out who the winners are.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.