Chinese rocket breaks apart after megaconstellation launch, creating cloud of space junk

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The first launch for a coming Chinese internet megaconstellation turned out to be quite messy.

On Tuesday morning (Aug. 6), a Chinese Long March 6A rocket launched the first 18 satellites for the Qianfan ("Thousand Sails") broadband network, which will eventually host up to 14,000 spacecraft.

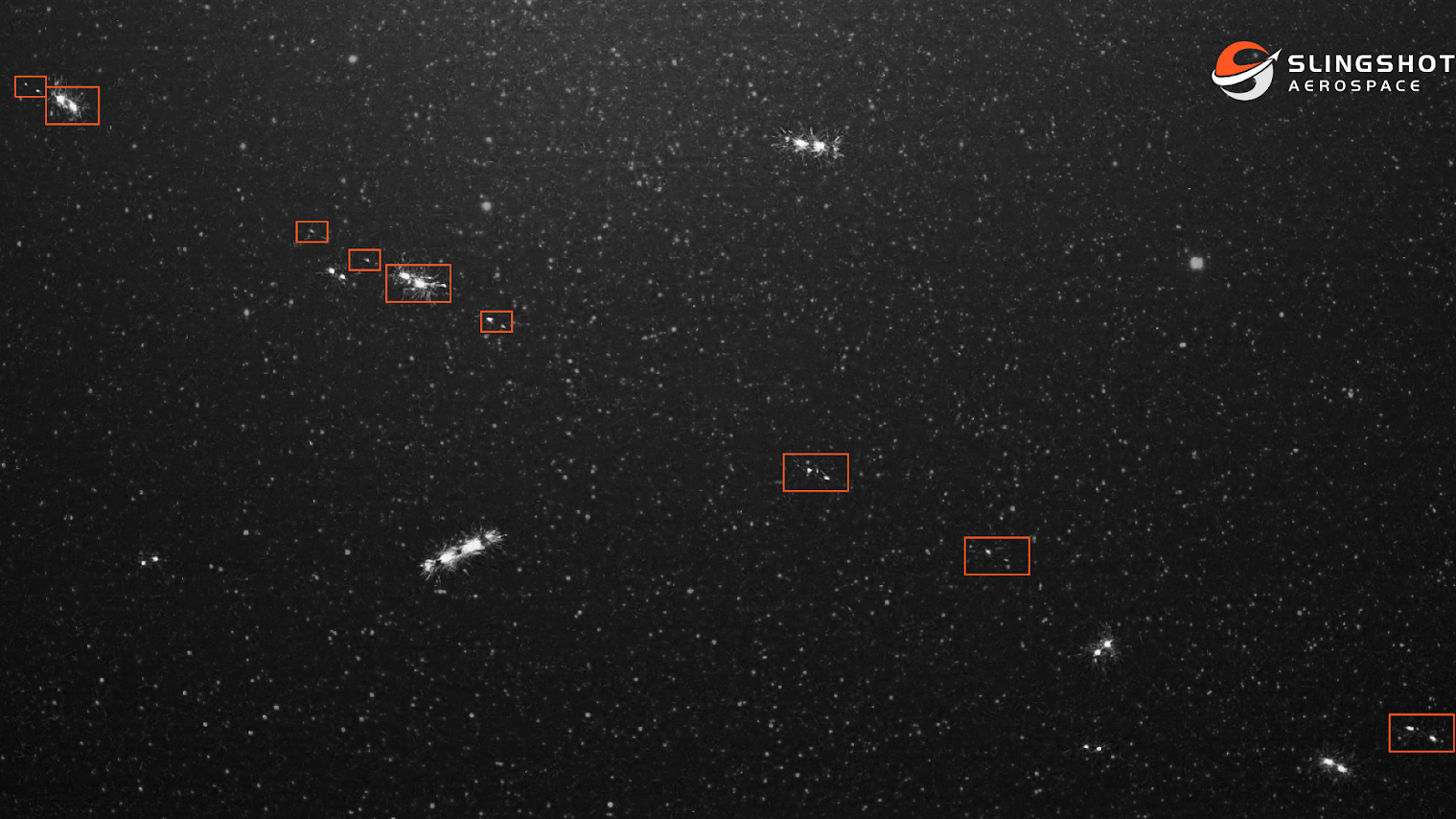

The rocket successfully delivered the satellites to low Earth orbit (LEO), at an altitude of about 500 miles (800 kilometers). But its upper stage broke apart shortly thereafter, generating a cloud of debris that's now racing around our planet, according to United States Space Command (USSPACECOM).

"USSPACECOM can confirm the breakup of a Long March 6A rocket launched on Aug. 6, 2024, resulting in over 300 pieces of trackable debris in low Earth orbit," the organization said in a statement today (Aug. 8). "USSPACECOM has observed no immediate threats and continues to conduct routine conjunction assessments to support the safety and sustainability of the space domain."

"Trackable debris" is generally any object that's at least 4 inches (10 centimeters) in diameter. The newly spawned debris cloud doubtless also contains many shards that are too small to monitor.

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the space debris problem

This was a worrisome start for the Thousand Sails constellation, according to Slingshot Aerospace, a California-based company dedicated to advancing space domain awareness and sustainability.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If even a fraction of the launches required to field this Chinese megaconstellation generate as much debris as this first launch, the result would be an untenable addition to the space debris population in LEO," Audrey Schaffer, vice president of strategy and policy at Slingshot, said in an emailed statement.

"Events like this highlight the importance of adherence to existing space debris mitigation guidelines to reduce the creation of new space debris and underscore the need for robust space domain awareness capabilities to rapidly detect, track and catalog newly launched space objects so they can be screened for potential conjunctions," she added.

This isn't the first time a Long March 6A upper stage — which weighs about 12,800 pounds (5,800 kilograms) without propellant — has spawned a debris cloud in orbit, as Slingshot noted. One of the rocket bodies broke apart on Nov. 12, 2022, shortly after deploying the Yunhai-3 weather satellite, according to NASA debris experts.

That event created 533 pieces of trackable debris by January 2023, according to the March 2023 issue of NASA's "Orbital Debris Quarterly News."

Earth orbit is getting more and more crowded, with both active satellites and pieces of debris. According to the European Space Agency, there are about 10,000 operational spacecraft zooming around our planet at the moment (most of them SpaceX Starlink internet satellites), roughly 40,500 pieces of debris at least 4 inches (10 cm) wide and 130 million shards at least 1 millimeter in diameter.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.