China launches classified satellites, tests landing nose cone with parachute

China sent three Yaogan 30 series satellites into orbit and used the launch to test controlling the rocket's falling nose cone with a parachute.

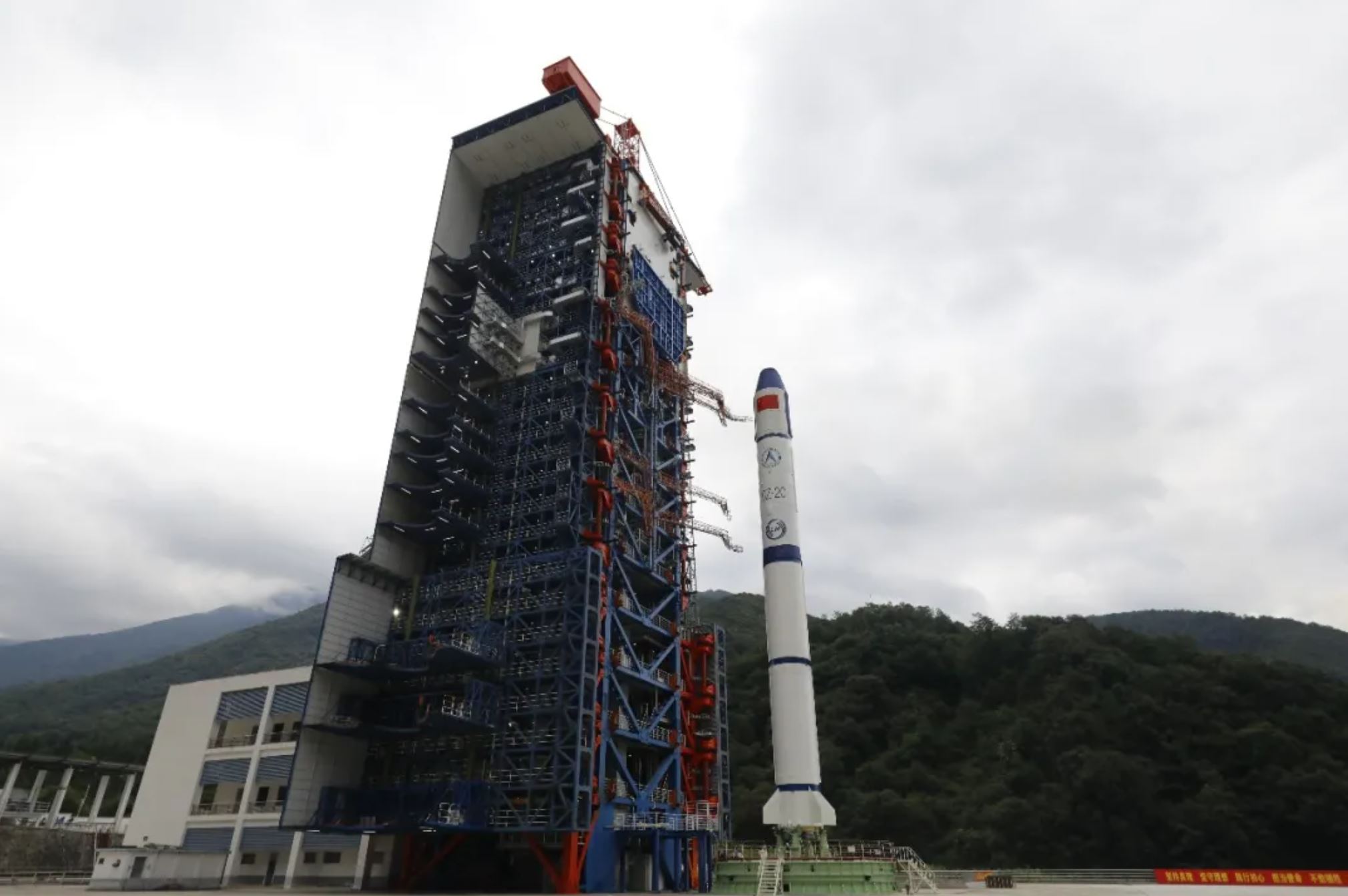

A Long March 2C rocket lifted off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in southwest China at 8:11 p.m. EDT July 18 (0019 GMT on July 19, or 8:19 a.m. local time), sending the 10th and final trio of Yaogan-30 satellites into orbit at an altitude of 370 miles (600 kilometers).

The satellites, according to Xinhua, "will survey the electromagnetic environment and verify relevant technologies by adopting multi-satellite network mode."

Related: The latest news about China's space program

Also aboard the flight was Tianqi 15, a small satellite for Internet of Things (IoT) data connectivity for the Beijing-based commercial company Guodian Gaoke.

No images and few details of Yaogan satellites are released, as is the international practice for launching classified satellites. Yaogan series satellites are understood by western analysts to be Chinese military reconnaissance satellites.

The orbital inclination of the satellites is 35 degrees, meaning the satellites pass over the Earth as far as 35 degrees north and 35 degrees south of the equator. This means the new Yaogan 30 satellites have a very similar orbit to the previously launched satellites in the series and orbiting together provide frequent passes over areas such as the South China Sea, East China Sea, Philippine Sea and Western Pacific.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The first Yaogan 30 series launch took place in September 2017. All 10 Yaogan 30 satellite launches took place at Xichang using Long March 2C rockets.

With this final launch in the series, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), a major rocket maker belonging to China's main space contractor, took the opportunity to test a technique for steering the nose cone, or payload fairing, after it detached from the rocket, as NASA Spaceflight reported.

China is not trying to catch the fairings to reuse, like SpaceX has previously, but rather to control where they fall. Launches from the inland Xichang spaceport often see debris such as spent rocket stages and fairings fall in inhabited areas, which risks damage to property and people and causes costly evacuations ahead of launch and cleanup operations.

Two days after launch, CALT revealed that the nose cone had been spotted during descent and later found in a wooded area. CALT says the goal is to reduce the area within which the fairing can land by 80%, improving the safety of the landing area and greatly reducing the need for evacuations.

(Like most rocket fairings, that of the Long March 2C splits lengthwise into two pieces during the launch sequence; statements don't clarify whether both halves were parachute-guided or only one.)

The mission was China's 24th orbital launch of 2021, with more than 40 planned for the year by China's state-owned space sector. Private and commercial companies are also planning their own launches.

CALT also tested a reusable suborbital vehicle earlier this month. The test is thought to be part of a project to develop a reusable spaceplane but China has revealed very few details.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.