Human influence on global warming is 'unequivocal,' UN report says

Hundreds of scientists reviewed more than 14,000 studies tracking climate change evidence worldwide.

Record-setting wildfires, historic floods, baking droughts and punishing heat waves have dominated headlines in recent months, and if you're wondering if these extreme events are linked to climate change — and if humans are responsible — a new report by hundreds of climate experts confirms that this is indeed the case.

In fact, it's "unequivocal" that human activity is driving climate change, and it's affecting Earth's oceans, atmosphere, ice and biosphere in ways that are "widespread and rapid," according to the report.

On Monday (Aug. 9), the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body for evaluating climate science, released the first installment of the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report in a virtual press event. In the report, the authors reviewed more than 14,000 studies that: document evidence of climate change; record the influence of human activities on global warming; and model predictions of our future should we fail to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change today.

Related: The reality of climate change: 10 myths busted

"The fact that the IPCC has agreed — with the agreement of all 195 member countries — that it is unequivocal that human activity is causing climate change, is the strongest statement that the IPCC has ever made," Ko Barrett, IPCC Vice Chair and Senior Advisor for Climate at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said at a briefing on Aug. 8.

Produced by the IPCC's Working Group I, this report addresses the scientific evidence of how Earth's climate is changing and how human activity is driving that change, summarizing the findings for global leaders and policy makers. Reports from two more working groups will be delivered by 2022; those reports will address climate vulnerability, impacts and adaptation in communities around the world, and potential strategies for mitigation, according to the IPCC.

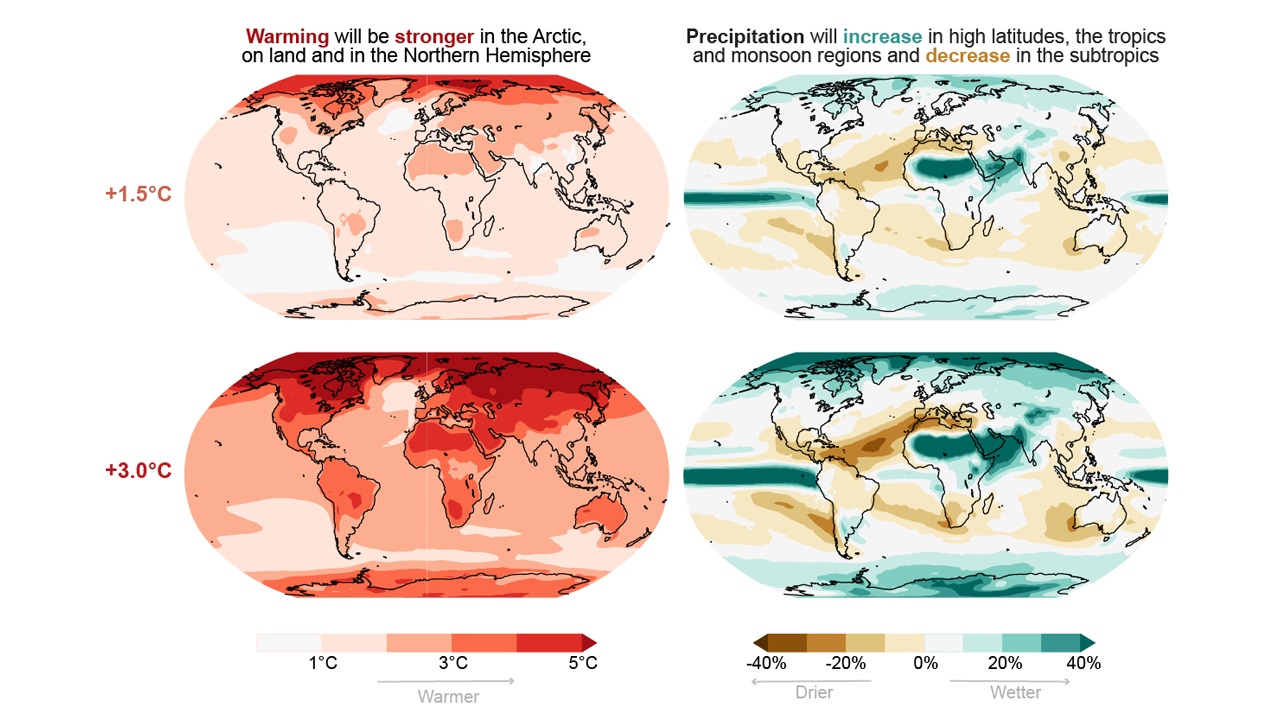

More than 200 scientists authored and edited the new report, and they found that human activity, primarily the production of atmospheric CO2 from the burning of fossil fuels, has driven global warming at a rate that is unprecedented in the last 2,000 years. Due to climate change, human communities everywhere on Earth are affected by extreme weather events that are longer, more intense and more frequent. If current warming continues, Earth will exceed 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) of warming and reach 3.6 F (2 C) by 2050, which will further intensify the severity of extreme weather.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Under all the future emissions scenarios that were considered in the report, "surface temperatures will continue to increase until at least the mid-century," the authors wrote.

Incremental changes

Levels of atmospheric heat-trapping CO2 are now higher than they've been in 2 million years; Arctic sea ice is at its lowest point in 1,000 years; and glacier retreat is at an unprecedented level for the past 2,000 years or more, according to the report. Seas have risen more in the past century than they did in the 3,000 years prior to that, at a rate of about 0.15 inches (4 millimeters) per year, and flooding events in coastal areas have doubled since the 1960s, Bob Kopp, an IPCC co-author and director of the Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, said at the briefing.

Heat waves on land and in the oceans are also more common now, occurring five times more often than they did in the 1950s. Severe droughts that used to take place once per decade have increased in frequency by 70% — and that number could double if global temperatures warm by 3.6 F, said IPCC co-author Paola Andrea Arias Gómez, an associate professor at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia.

"The fact that the IPCC has agreed — with the agreement of all 195 member countries — that it is unequivocal that human activity is causing climate change, is the strongest statement that the IPCC has ever made."

Ko Barrett, NOAA

Powerful hurricanes are also forming more frequently — and deposit more rainfall — than they did decades ago; and most land areas are seeing precipitation events that are more frequent and intense, according to the report.

"With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger," the authors wrote. For example, extreme heat waves that used to happen once per decade now occur about three times in 10 years. With an increase of just 0.9 F (0.5 C) in global average temperatures, such heat waves would happen four times per decade, and resulting temperatures would be nearly 3.6 F (2 C) hotter. Record-breaking heavy rainfall events and droughts would similarly increase in frequency and intensity, should Earth continue to warm, the scientists reported.

No turning back

"There's no going back" to the climate that persisted on Earth for thousands of years, Barrett said at the IPCC briefing. However, some of the changes that we're now seeing can be slowed or even stopped in their tracks if we can limit the rise of global temperature averages to no more than 2.7 F above pre-Industrial levels, Barrett said. But without large-scale reductions in emissions that are currently warming the planet, that goal "will be beyond reach," she added.

"Achieving global net zero CO2 emissions is a requirement for stabilizing CO2-induced global surface temperature increase," the researchers wrote in the report.

Limiting warming to below 3.6 F would also dramatically affect sea level rise, Kopp added. Under current warming, oceans are on track to rise 7 feet (2 meters) by the end of the century. Ice loss from glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica is irreversible and is expected to continue for decades, so oceans will still rise even if global temperatures are cooler — but the process will lengthen by centuries "and possibly millennia," Kopp said.

"Even in the case where we're talking about the most extreme example of irreversible changes, which is the sea level and the ice sheets, there's a huge impact on how quickly that comes, and therefore how manageable those changes are," he said.

Future scenarios with low or very low emissions offer the most promising outcomes, with effects that could be noticeable within two decades, according to the report. While it's still possible to head off many of climate change's most dire impacts, "it really requires unprecedented transformational change [with] rapid and immediate reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050," Barrett said at the briefing.

"The idea that there is still a pathway forward, I think, is a point that should give us some hope," Barrett said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.