The sun as you've never seen it: European probe snaps closest-ever photo of our star

Solar Orbiter took the image when it was exactly halfway between Earth and the sun

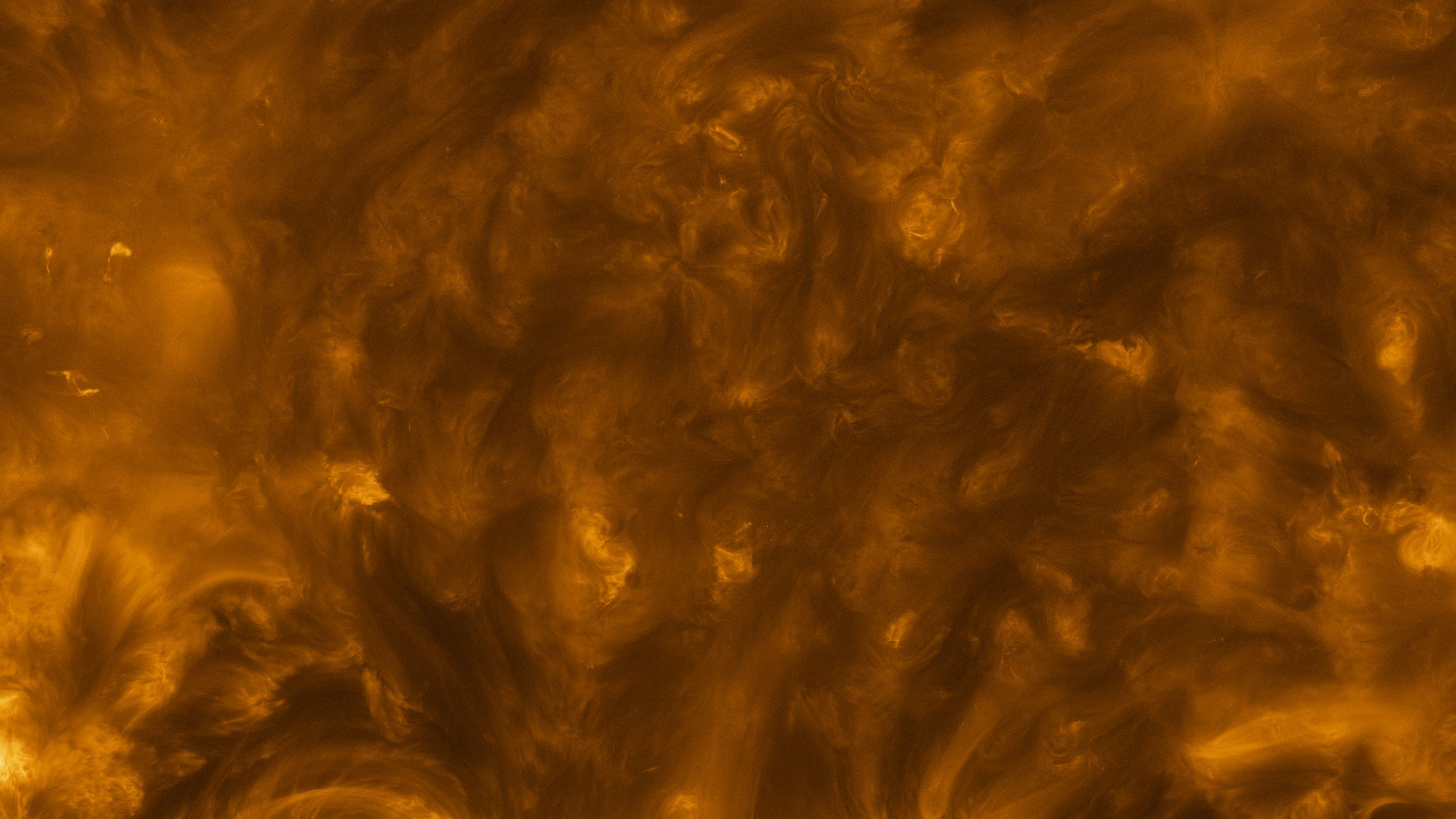

The European sun-chasing spacecraft Solar Orbiter has snapped the closest images of the sun ever taken, revealing the finest details of our star's outer atmosphere, the corona.

The images were taken on March 7, when Solar Orbiter was exactly halfway between Earth and the sun, at a distance of 46 million miles (75 million kilometers) from both bodies.

One of the instruments turned on during this opportunity was the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), which sees the universe in the highest-energy part of the ultraviolet component of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Due to Solar Orbiter's close proximity to the sun EUI had to take 25 individual shots to image the entire solar disk, the European Space Agency (ESA) said in a statement. It took four hours for the EUI team to capture all the segments, as each shot required a 10-minute period, including the time needed to repoint the spacecraft, ESA said.

Related: Solar Orbiter spacecraft captures huge eruption on the sun (video)

And better images are coming soon. Since the spacecraft's launch in February 2020, ground control teams have been gradually tightening Solar Orbiter's trajectory around the star at the center of our solar system. While the two previous perihelions — the points in the spacecraft's elliptical orbit closest to the sun — took place at about half the sun-Earth distance (47.8 million miles or 77 million km), Solar Orbiter is now heading for a much closer encounter.

On Saturday (March 26) at 7:50 am EDT (1150 GMT), the spacecraft will zoom past the sun at a distance of only 30 million miles (48.3 million km), about a third of the sun-Earth distance, ESA's Solar Orbiter deputy project scientist Yannis Zouganelis told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Solar Orbiter's distance from the star will then start to increase again, but its future close passes will take it even closer: just 26 million miles (42 million km) away from the sun's surface. No other spacecraft equipped with a camera has ever gotten this close to the sun. NASA's Parker Solar Probe makes deeper dives toward the star, up to a few million miles away, but due to the extremely high temperatures at those distances, the spacecraft can't carry a sun-facing camera.

During the imaging campaign on March 7, Solar Orbiter operators also took images with the spacecraft's Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument, which revealed the temperature gradient throughout the sun's atmosphere. The strange thermal behavior of the sun's atmosphere is one of the star's greatest mysteries. Instead of getting colder with distance, the sun's atmosphere is actually considerably hotter at higher altitudes.

While the sun's surface is "only" about 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,000 degrees Celsius), the temperature of the outer atmosphere, the corona, soars to nearly 1.8 million degrees F (1 million degrees C).

The SPICE measurements revealed individual layers of the sun's atmosphere, starting with the lowest layer, the chromosphere, at 18,000 degrees F (10,000 degrees C), all the way up to 1,130,000 degrees F (630,000 degrees C) in parts of the corona.

In the images obtained by Solar Orbiter during its first close pass in June 2020, scientists discovered miniature solar flares dubbed campfires. These campfires, predicted by the recently deceased solar physicist Eugene Parker, could explain this mysterious heating, scientists believe.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.