As Comet ATLAS crumbles away, Comet SWAN arrives to take its place for skywatchers

As I write these words, Comet ATLAS, which a month ago looked like it might evolve into the first really bright naked-eye comet in a decade, is now falling apart. It has fragmented into several pieces, quickly dispersing and not leaving behind enough material to produce any kind of significant display.

Soon after this comet was discovered near the end of 2019, it brightened at an almost furious pace. That combined with the fact that it was traveling in the same orbit as the "Great Comet" of 1844 suggested that it might be a fragment of that famously spectacular comet, and that by the spring it might evolve into a beautiful celestial showpiece that could possibly excite the world as well as inject some new interest and exposure to the science of astronomy.

Sadly, those expectations will not be met.

Once again, the fickle, unpredictable nature of comets came into play as we here at Space.com couched our initial projections as to what might — or might not — happen concerning the future of Comet ATLAS.

Related: The 9 most brilliant comets ever seen

Back in another time, astronomers probably would have relied on one particular set of predictions as to how bright the comet might ultimately get. However, during February and especially March, in this age of an internet run amok, we were seeing radically conflicting information and opinions from both bona-fide and "wannabe" experts. Some had suggested that ATLAS might rival Venus or even the moon in brightness!

Lacking a crystal ball, we felt it best to convey the full range of possibilities, from a bright naked-eye comet adorning the western evening sky in late May, to an object that might completely fizzle out. Unfortunately, ATLAS decided to pursue its own agenda, befuddling even veteran comet observers and not behaving like any previous comet. Despite claims to the contrary by some in the mainstream media, nobody knew for certain exactly what ATLAS was going to do.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Breaking up wasn't hard to do

We had sounded an alarm in a column about the comet on April 6, when we pointed out that the amazing brightening trend of Comet ATLAS "hit a wall" on St. Patrick's Day (March 17) and by early April it actually began to fade. Prophetically, well-known comet expert John Bortle had suggested to Space.com that ATLAS could be "several magnitudes fainter than we currently assume it to be and may or may not, be large enough to survive perihelion passage."

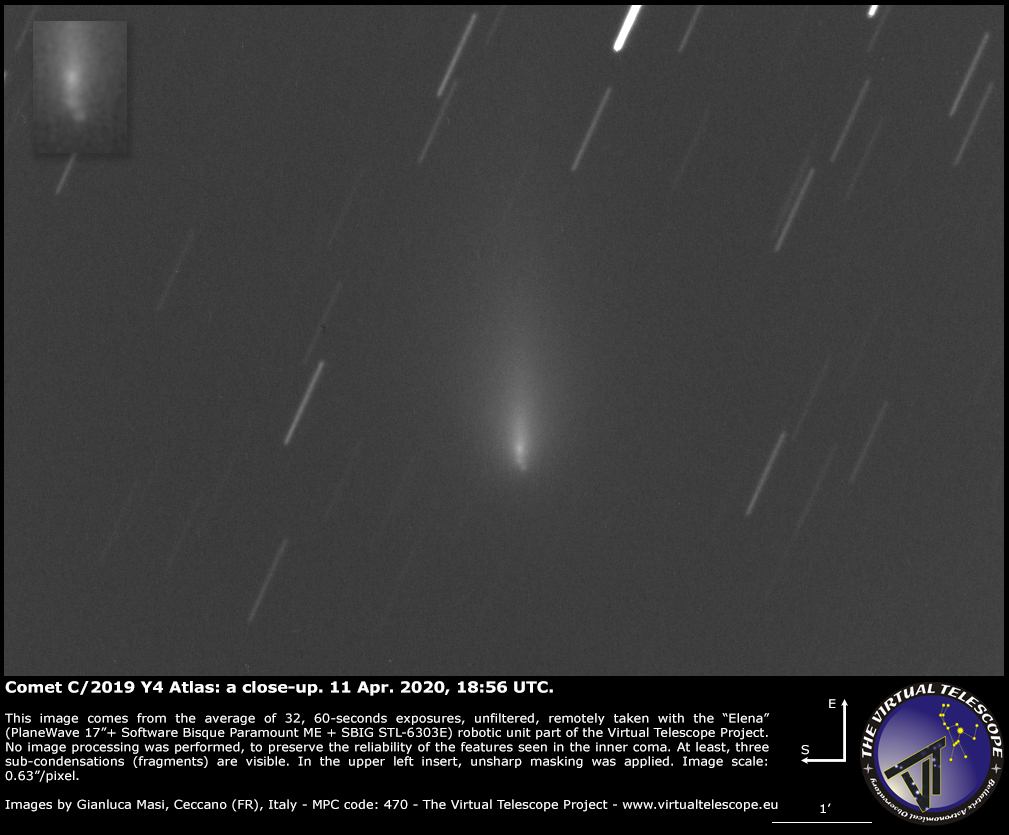

And at the same time that our story was published, astronomers Quanzhi Ye (University of Maryland) and Qicheng Zhang (Caltech) submitted a report to The Astronomer's Telegram (a bulletin board of astronomical observations posted by accredited scientists) titled "Possible Disintegration of Comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS)." Their findings showed that the comet's head, or coma, of the comet was rapidly elongating, suggesting that the comet nucleus was beginning to fragment.

Confirmation of this came on April 11, when images of ATLAS revealed that its nucleus had broken into at least three pieces. It is not yet clear exactly what caused the comet to break apart, but this is likely the beginning of the end for ATLAS. The comet continues to show indications of breaking up as well as slowly fading away. Indeed, as Bortle had suggested, there may be nothing left when ATLAS makes its closest pass at the sun on May 31.

But even as Comet ATLAS slowly goes to pieces, another comet has moved in to take its place.

Enter Comet SWAN

On April 11, the same day that ATLAS broke into three pieces, amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo discovered a new comet while looking at data from NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

Michael Mattiazzo’s new SWAN comet (C/2020 F8?) is surprisingly bright and visible in 15x70 binoculars, despite the moon. Here is an 6 minute exposure. Image Terry Lovejoy pic.twitter.com/Jb38RwiiYLApril 11, 2020

The comet suddenly appeared in images from SOHO's Solar Wind ANisotropies instrument, which goes by the acronym "SWAN." Mattiazzo has discovered eight comets since 2004 by carefully checking SWAN data most every day.

SOHO's SWAN instrument was not designed to find comets; its job is to survey the solar system for hydrogen. But because the comet is spewing a fairly significant amount of hydrogen in the form of water ice, it was picked up by SWAN.

Coincidentally, Mattiazzo lives in Swan Hill, Victoria, Australia.

A prehistoric visitor

The new comet appears to be traveling in a very elongated ellipse. For fun, I fed its orbital elements, which includes the eccentricity of its path around the sun, into an orbital simulator.

My simulation suggests Comet SWAN is traveling around the sun in a period of about 25 million years. This means that the last time it swept through the inner solar system may have been during the Oligocene Epoch, when Paraceratherium, a genus of hornless rhinoceros and one of the largest terrestrial mammals, was walking the Earth.

Future developments

Currently, Comet SWAN is only accessible to those south of the equator. It is currently located in the faint constellation of Sculptor, not far from the first-magnitude star Fomalhaut. As of April 16 it was shining at magnitude +7.8 — easy enough to pick up in good binoculars — and displaying a head roughly one-sixth the apparent width of the moon.

The question is, will SWAN evolve into a bright object? The consensus is: "maybe." Like ATLAS, Comet SWAN appears to be a relatively small comet. It will pass closest to Earth on May 12 at a distance of 51.8 million miles (83.3 million kilometers), and it will be at its closest point to the sun (called perihelion) on May 27, when it will be 40 million miles (64.4 million km) away from our star.

Assuming Comet SWAN continues to brighten at its current pace, it could reach third magnitude during the final week of May. That would make it bright enough to be visible to the naked eye just when those of us in the Northern Hemisphere might have an opportunity to see it, both very low in west-northwest sky after sunset and again very low in the east-northeast sky before sunrise.

But the fact that the comet appeared quite suddenly suggests that it might be undergoing an outburst in brightness and that after a few days or weeks, SWAN might undergo a fade-down — or even possibly break up in much the same fashion as did Comet ATLAS.

In other words, SWAN ultimately could end up as an "ugly duckling."

We will be monitoring Comet SWAN closely in the coming weeks and will provide another update regarding its development next month. So stay tuned!

Editor's note: If you have an amazing comet photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, you can send images and comments to spacephotos@futurenet.com.

- April is the month of Venus! See the 'evening star' at its brightest

- Photos: Spectacular comet views from earth and space

- Comet quiz: Test your cosmic knowledge

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

<p>For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of <a href="https://www.space.com/your-favorite-magazines-space-science-deal-discount.html" target="_blank">our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.