During the next couple of weeks we'll have a chance of seeing a new comet as it sweeps past the sun.

The comet's name is SWAN, an acronym for the Solar Wind Anisotropies camera on NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). Officially designated as C/2020 F8, the comet was discovered by Australian amateur astronomer, Michael Mattiazzo, while exploring SWAN imagery on March 25.

Comet SWAN initially caught Mattiazzo's attention because it apparently was undergoing a sudden outburst of hydrogen gas — something that SOHO's SWAN instrument is particularly well adapted to picking up. Water ice from the comet's nucleus evaporates as the comet approaches the sun. Solar ultraviolet radiation splits up water molecules, and the liberated hydrogen atoms glow in ultraviolet light.

Related: The 9 most brilliant comets ever seen

The comet was 135 million miles (217 million kilometers) from the sun when Mattiazzo first saw it, but it will ultimately come to within 40.2 million miles (64.6 million km) of our star when it arrives at its perihelion, its closest point to the sun, on May 27.

In scanning the Internet I've seen comments about Comet SWAN describing it as (potentially) putting on a "splendid" show in the coming days, and how it could be the "best comet in years" or the "brightest in decades."

Well ... don't count on that.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sorry if I sound like the wet blanket at the party, folks, but it seems to me that many who are ballyhooing Comet SWAN as a possible celestial showpiece are forgetting some of the old basics of forecasting what a lot of comets tend to do: Tease us, and more often than not end up underperforming and disappointing.

This is how comets greet: by wagging the tail! Hi Earthlings!#FollowTheComet! https://t.co/xpdOFvvNUnMay 5, 2020

In recent days, some very impressive images of Comet SWAN have been making the rounds on different astronomy sites, all showing a comet with a large glowing head (called the "coma"), trailed by a long and beautiful gossamer tail.

I'm sure that one look at those photographs, combined with the promise that viewers could see such a spectacle with their own eyes, will have many making a special effort to go out and see it for themselves.

But what you see in those photographs, is not what you're going to get.

Is it a dusty comet, or a gassy one?

Comets are composed of frozen gases — methane, ammonia, water vapor and many others — that are heated as they approach the sun and made to glow by the sun's light, much in the same manner as phosphorescent paint glows under an ultraviolet lamp. Mixed within the gas are particles of mostly fine-grained and dusty material.

Now the best comets — the ones that put on a good show — contain a lot of dust. Dust, you see, is a very good reflector of sunlight. As the gasses warm and expand, the solar wind (a stream of subatomic particles rushing out from the sun) blows the expanding material out into space to form the comet's beautiful tail.

If the comet is a dusty one, the coma and resulting tail will be bright and easy to see. On occasion you may even perceive a slight yellow or pinkish tint. The dust may actually lag behind the comet head and impart the shape of a gentle arc. Comet Bennett (1970), Comet West (1976), Comet Hale-Bopp (1997) and Comet McNaught (2007) are all examples of bright and dusty comets.

But if the comet is primarily composed of gas, it will generally appear much dimmer; more "ghostly" than anything else. Such comets usually appear as nothing more than a fuzzball to the eye, and the resulting tail will tend to be a faint and narrow appendage, stretching straight out from behind the coma.

Moreover, to the naked eye and even through binoculars or a small telescope, the gas tail (usually of a bluish tint) tends to be so faint that it is hardly evident at all. Ironically, long-exposure photographs will bring out the gaseous tail quite nicely. Such tails can be rather long and stretch for many degrees across the sky, although what the camera sees is deceptive, for visually with your eyes, only a fraction of that length tends to be evident, again because of the faintness of the gas projected against the background of the sky.

Now, guess what type of comet SWAN happens to be? If you said "gas" you're (unfortunately) correct.

It's also a "newbie."

Initially, Comet SWAN looked like it was traveling in a very elongated ellipse with an orbital period in the tens of millions of years; a comet that had been here at least once before. But that doesn't appear to be the case now.

Rather, Comet SWAN appears to be a "new" comet; a "virgin" from out of the Oort Cloud, a shell of icy bodies at the outskirts of the solar system that is considered the "breeding ground" of comets. New comets, or comets that have not swept around the sun before, travel in parabolic orbits because they literally fall from the depths of space toward the sun in a straight line, swing around the sun and are then flung back out into space.

Such first-timers have never interacted with the sun before and are covered with very volatile materials such as frozen nitrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. These ices vaporize far from the sun, giving a distant comet a rapid surge in brightness that can raise unrealistic expectations. But once those ices are gone, the comet's rapid brightening dramatically slows.

Once sizzling ... now fizzling?

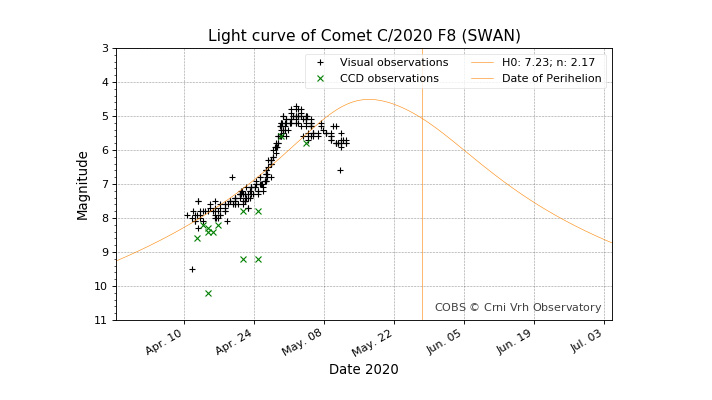

And that drop in brightness is exactly what has appeared to have happened to Comet SWAN, based on observations taken from the Comet Observation Database (COBS).

On April 24, the comet was shining at magnitude +7.2, which is too faint to be seen with the naked eye and only accessible with binoculars or telescopes. Magnitude is a measure of the brightness of a star or other celestial body. The brighter the object, the lower the number assigned as a magnitude. The brightest stars are magnitude 0 or +1; the faintest stars visible without optical aid are +6.

Less than a week later, on April 30, the comet's brightness had surged more than six-fold, reaching magnitude +5.2. By that time, the comet was faintly visible in a dark sky with the unaided eye. But ever since then, the comet's brightening has stalled and even has appeared to dim a little, hovering at around magnitude +5.6.

"I don't like what I'm seeing in F8 SWAN's light curve," Robert Pickard, a member of the International Comet Quarterly (ICQ), noted in a post to the ICQ Facebook group. "I see an outburst, followed by fading, then some recovery, then more constant fading."

The comet's fuzzy coma appears around 7 arc minutes in diameter — that's roughly one-quarter the apparent size of the moon. In terms of a linear size, that's roughly 107,000 miles (172,000 km) in diameter.

At perihelion on May 27, early forecasts had the comet reaching a peak brightness of magnitude +3.5 or about as bright as a star of medium brightness. It might still do that if it undergoes another surge, but if not, it could remain at the same level of brightness — or get even dimmer — compared to now.

In a word: faint.

"Now there are two tails, both faint. We will be losing the comet and handing it over to more northerly horizons," longtime skywatcher Stephen O'Meara, who has been observing Comet SWAN from Maun, Botswana, told Space.com. "Hopefully, the dustiness will continue to increase as the comet nears the sun and give you guys a decent dust tail, rather than a domino tail. Fingers crossed."

Where and when to look

From now through early June, Comet SWAN will track north and east from the constellation Triangulum, into Perseus and will enter Auriga on June 1. From now through May 24, your best chance of catching a view of the comet will be in the morning sky.

Start looking about 60 to 70 minutes before sunrise. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees. The comet should appear roughly 10 degrees above the northeast horizon; not likely immediately evident to the unaided eye, so scan the sky with binoculars.

What you'll be looking for is a diffuse, circular glow, possibly accompanied by a faint tail pointing upward and to the right.

Then starting on May 25, best chances of seeing the comet will transition to the evening sky. About 60 to 70 minutes after sunset, the comet will be positioned about 10 degrees above the north-northwest horizon, with any semblance of a tail pointing upward and to the left. Perhaps your best shot at getting a glimpse of Comet SWAN will come on the evening of June 2nd to the lower left of the brilliant yellow star Capella.

Clear skies and good luck!

- As Comet ATLAS crumbles, Comet SWAN arrives to take its place

- Comet ATLAS disintegrates into pieces as Hubble telescope watches (photos)

- How the 'comet of the century' became an astronomical disappointment

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.