The dazzling Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is emerging in the night sky: How to see it

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is arriving at its projected pinnacle of brightness, followed by a transition into the evening sky.

Currently, it displays the classic look for a bright comet, flaunting a starlike head and a prominent tail. As we crossed over from September into October, a consensus of observations reported on the Comet Observations Database (COBS) placed the comet somewhere between first and second magnitude. (The larger the figure of magnitude, the fainter the object).

The coma (comet head) currently measures about 130,000 miles (209,000 kilometers) in diameter, accompanied by a tail stretching out for some 18 million miles (29 million km).

Until now, the comet has been visible primarily for those living in the Tropics and the Southern Hemisphere, though in recent days, the comet has made itself evident to those across parts of the United States, albeit deep in the dawn twilight, hovering low above the east-southeast horizon. Soon, however, observers across the Northern Hemisphere will get their first really good look at this newest visitor to the sun.

And the timing couldn't be better, because the best is yet to come!

Related: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS wows skywatchers around the world and astronauts in space (photos, video)

Still mired in the twilight glow

Right now, as Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS continues to make its way through the inner solar system, it is shining as brightly as the brightest stars, but it is also enmeshed in the twilight glow of the sun. So, despite its extreme brightness, making an actual sighting of this object will not be a slam dunk.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

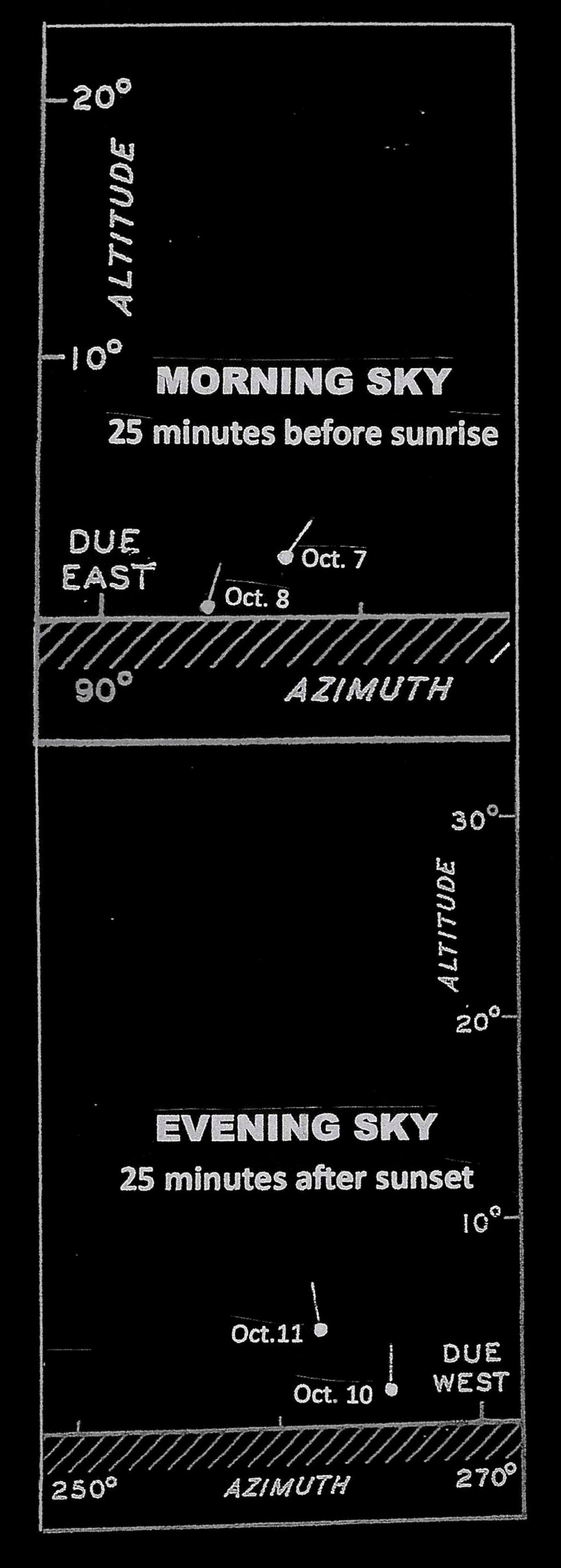

However, knowledgeable amateur astronomers have a fair chance of spotting Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS during the next several days. The comet will appear either very low in the bright glow of morning twilight, about 25 minutes before sunrise (Oct. 7 and Oct. 8) and/or evening twilight, about 25 minutes after sunset (Oct. 10 and Oct. 11).

Scanning along the horizon with binoculars will be very beneficial, as the comet might not be immediately visible to the naked eye thanks to its low altitude and being embedded in the bright twilight glow. But once you've picked up the comet, you can try to see it without any optical aid.

People with GoTo scopes — a type of telescope mount and related software that can automatically point a telescope at astronomical objects that the user selects — can refer to specific celestial coordinates provided by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The comet is cataloged as C/2023 A3. Note that the data is given for 0h Universal Time, which corresponds to evening on the previous day in North America. So, if you're on Central Daylight Time, for example, which runs five hours earlier than UT, and you're looking for the comet at 7:00 p.m. on Oct. 11, then the coordinate positions for Oct. 12 will be exactly correct.

Daytime visibility?

How bright will Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS ultimately get? Complicating any estimates is the fact that the comet passes almost directly between the Earth and the sun. For example, Joseph N. Marcus, a retired pathologist and veteran amateur astronomer with a particular interest in comets, has assessed the degree of how much of the comet's tiny particles of ice and dust will be backlit by sunlight, creating an effect known as forward-scattering. This can make a comet appear significantly brighter because the dust and ice crystals reflect and enhance its apparent brightness by scattering that light toward the observer.

In making comparisons with another comet — Comet McNaught (C/2006 P1) — which had a similar orbital geometry relative to the Earth, Marcus makes reference to a technical paper he wrote in October of 2007. Marcus has since concluded that, on Oct. 9, this same enhancing effect could help Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS ramp-up to a peak magnitude possibly approaching minus 5. That's as bright as the planet Venus!

Theoretically, that could make the comet bright enough to glimpse in the daytime.

The comet will be passing just above the sun, possibly tempting some to try and see it as a speck of light by blocking out the dazzling disk of the sun with their thumb or outstretched hand.

However, as in the case of watching a partial solar eclipse, there are inherent dangers in attempting to sight a comet so close to the sun. Viewing the comet itself poses no danger, but potential danger lies in staring at the sun. The sun's radiation can burn your retinas and cause irreparable damage, all without causing any pain. It should be emphasized that neither sunglasses, telescopes nor binoculars will protect against the type of eye damage that could ultimately result in blindness, when a person — however briefly — looks directly into the sun's rays.

The safest way to watch

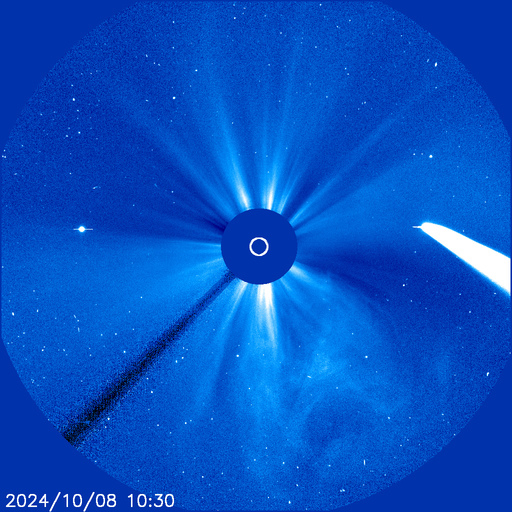

By far the safest way to watch the comet's close brush with the sun is to view it on your computer screen, courtesy of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). Astronomers hope to get spectacular views of the comet by utilizing SOHO's LASCO (Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph Experiment) C3 camera and by accessing either near-live images or videos that span the preceding 24 hours.

Back in January of 2007, the public was captivated when SOHO captured Comet McNaught sweeping closely past the sun. Since it was launched in 1995, SOHO imagery has detected literally thousands of otherwise unknown comets, in fact generating a competition among a handful of armchair astronomers. To date, SOHO officials have reported more than 5,000 comet discoveries using the spacecraft's LASCO C3 imagery.

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS will be within range of the LASCO C3 imagery through 22:00 UT (6:00 p.m. EDT on Oct. 10). It will appear to pass closest to the sun — a scant 3.5-degrees from its center — on Oct. 9 at 09:00 UT (5:00 a.m. EDT).

A leap into the evening sky

Probably as far as most are concerned, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS will put on its best showing in the evening sky during the two-week timeframe beginning Oct. 12 and running through Oct. 26. By then, the comet will be the largest visible object in the solar system and the closest to the Earth beyond the moon.

The comet will practically vault into evening prominence during the middle of October. On Oct. 12, during mid-twilight (45 minutes after sunset), you will find Tsuchinshan–ATLAS approximately 6 degrees above the west-southwest horizon. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures 10 degrees in width, so the comet will stand about "one-half fist" above the horizon and will set about 90 minutes after sunset.

But during the week, the comet's altitude above the horizon will increase by about 3 degrees per night; each evening, it will be setting about 16 minutes later.

Dark skies provide the best views

Locate a good observing site in advance and get there early. You'll need an open view of the west-southwest horizon. There should be no artificial lights nearby and no big cities or towns that significantly illuminate the sky. Initially, the comet will likely be visible even from cities and suburban locations, but by later in the month, the most impressive views will be from dark country locations where the sky is really black.

One object that will unfortunately "muscle-in" on the comet with its bright light will be the moon, which, at the beginning of the two-week observing window will be in a waxing gibbous phase, shining brightly in the eastern sky at dusk. It turns full on Oct. 17, rising as the sun sets, but on each successive evening thereafter, it will rise about 50 minutes later, making its light less troublesome for our comet adventures.

Tail may change dramatically

The comet will pass nearest to Earth at 15:39 Universal Time (11:39 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time) on Oct. 12. At that moment, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS will be 43,911,824 miles (70,669,230 km) from our planet.

The comet's tail will be pointing almost directly toward the Earth on that date, so it may appear rather foreshortened in appearance. But in the days that follow, the tail will appear to pivot rapidly to the east (left) and lengthen significantly with each passing night. As a result, dramatic night-to-night changes in the tail may become evident.

To see the expected evolution of the tail, check out these wonderful animations rendered by Nicholas Lefaudeux, a French optical engineer and amateur photographer, which depict different perspectives of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS as it approaches and sweeps around the sun and heads back out into deep space.

There is even a chance during the few evenings after Oct. 12 at catching a glimpse of a rare "anti-tail." While the tail of most comets usually points directly away from the sun in the sky, on occasion, leftover dust particles released by the comet nucleus is left to drift in the wake of the comet's orbital plane (this refers to the comet's trajectory around the sun). When Earth crosses through a comet's orbital plane, some of this dust is reilluminated by the sun and can appear as a bright spike or sunward fan pointing from the comet's head almost in the opposite direction to its primary tail, depending on the comet's trajectory and orientation. But in reality, this is merely an optical illusion, and there is no extra tail.

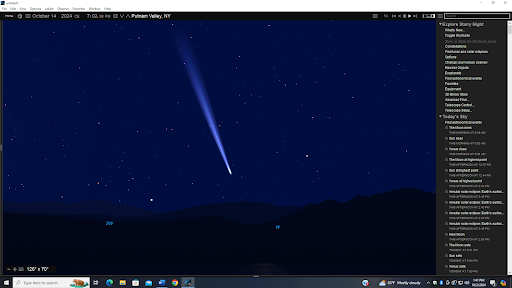

Climbing higher; setting later

By the evening of Oct. 14, the comet will be well-positioned in the sky, midway between Venus (to its upper left) and the bright orange star, Arcturus (to its lower right). The comet will be situated about 21 degrees (roughly "two fists") from both the planet and the star.

By the evening of Oct. 19, the comet will be nearly 30 degrees ("three fists") above the west-southwest horizon at mid-twilight and will be setting three and a half hours after sunset. By Oct. 26, these numbers will have improved to 38 degrees above the west-southwest horizon (almost "four fists") and setting four and a half hours after sunset.

Getting fainter; but tail growing longer

After Oct. 12, the comet will be moving away from both the sun and the Earth, so consequently it will gradually fade. On the evening of Oct. 12, the comet's head (called the coma) should be shining as brightly as a zero-magnitude star. By Oct. 16, it may have dimmed to second magnitude — though that's still as bright as Polaris, the North Star.

By Oct. 19, forecasts suggest Tsuchinshan–ATLAS will be shining at third magnitude; no brighter than an ordinary star. And by the time we get to Oct. 26, the comet will have probably diminished to fifth magnitude; the equivalent of a very faint star visible with the naked eye only from a dark location, far from any light pollution.

But while the comet grows fainter, a broad, yellowish-white dust tail is likely to grow, curving off to the left away from a much fainter, thin, straight and bluish gas, or "ion tail."

In fact, during mid- to late-October, the comet's tail might unfurl to a length of 20 degrees — even 30 degrees is not completely out of the question. After that, however, it will shrink and fade rapidly as the comet departs back into deep space.

Goodbye and farewell

You’ll be able to follow Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS with binoculars or a small telescope for perhaps another month or so. It likely came directly from the Oort cloud — a vast bubble of frozen material extending about halfway to the nearest star. This cloud is hypothesized to contain billions, or perhaps even trillions, of comets surrounding our solar system.

As to exactly how long it might take for this comet to make one circuit around the sun, astronomer Daniel Green of the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts points out that, because the shape of its orbit appears so very close to a parabola, plus factoring in observational uncertainties, "it makes no sense to talk of orbital periods, especially since it likely was also perturbed gravitationally by the major planets of the solar system." He adds that, "As more observations are obtained, we'll eventually be able to extend the path of the comet's orbit through the inner solar system, and get a better handle on the comet's 'original' and 'future' orbits."

Regardless, this will be Tsuchinshan–ATLAS' first — and last — performance for all of us.

So, "comet" get it!

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.