The third episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson's rebooted "Cosmos" series, titled "Lost City of Life," takes viewers on a journey through space and time to witness the tenacity and creativity of life on Earth and the prospects of life throughout the universe.

We begin in space, looking at a beautiful claret-colored cloud of swirling cosmic dust and gas — it's 11 billion years ago, and this is the birthplace of the Milky Way galaxy, a "chaotic, stellar nursery," as Tyson puts it. Bright stars appear in the swirling panorama, and as we speed through time, these hot, early stars die out and fertilize what is to come — us. As Tyson echoes Carl Sagan's sentiments, "We are made of star stuff."

From this stellar origin, this episode moves through space and time, from world to world, from the earliest phases of the universe to the present day. It's a big, overarching topic this week, this thing we call life. Buckle up.

Related: 'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' takes us back into a universe of science

Within moments we swing out to an arm of the Milky Way and watch our solar system being born. Jupiter coalesces from the primordial disk first, followed by the other planets. At their cores, these worlds are composed of elements of stars long dead — all part of the cycle of life in our cosmos. After narrating this science-based version of a creation myth, Tyson asks his viewers: "Does the cosmos give rise to life as naturally as it gives rise to stars and worlds?"

He rides the Ship of the Imagination down into the primordial oceans of Earth — a roiling, violent place — where we slowly weave through towers of calcium carbonate, rising with impunity from the seabed. He calls these a "lost city of life." These towers have been formed by inorganic processes across the globe over tens of thousands of years, but change is coming, and it's called life.

Shrinking a thousand times, we plunge into a crack in one of these gigantic spikes and look down into a red maelstrom heated by the Earth's mantle. Bursts of organic molecules swirl past us, driven by upwelling plumes of superheated seawater. "It was the beginning, at least in our little part of the cosmos, of an engineering collaboration between the minerals of earth is the rocks and land," Tyson says.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The basic elements of life are beginning to collect in pores scattered across these towers, in this "city of life," and prominent among them is an abundance of olivine, a mineral common in the crust below. These beautiful translucent-green olivine crystals soon undergo a process called serpentinization, in which heat, pressure and water combine to release hydrogen, methane and other ingredients that helped organic molecules transform into the earliest living organisms.

Shrinking still smaller, we observe this process happening inside the olivine crystals, and Tyson says, "We think it was that chemical reaction that provided the energy that powered the first cell, that was the spark that electrified the building blocks of life into something alive."

Then, apocalypse. Moving forward through time, to about 2.3 billion years ago, a blue-green algae called cyanobacteria have engulfed the planet. The oceans of Earth are full of life, and a war rages between the dominant cyanobacteria and anaerobes, or single-celled organisms that live without oxygen and envelope the planet with carbon dioxide. Because carbon dioxide is a less efficient greenhouse gas than the methane that it replaced, Earth's atmosphere began capturing less heat from the sun, and freeze and thaw cycles ensued for a billion years.

Then, 540 million years ago, the next great act emerged: the Cambrian explosion. Microbes evolved into larger creatures that swam, slithered and eventually crawled across the planet. Life had escaped its early confines, and the Earth was forever transformed.

We plunge into the age of science, when humans were starting the journey into understanding our origins, and meet a brilliant scientist named Victor Goldschmidt takes it a step further. As Tyson puts it, "Goldschmidt saw the Earth as a single system. He knew that in order to get the whole picture, you couldn't just know physics, chemistry or geology."

Over the next 30 years, Goldschmidt would reinvent the periodic table and, while being persecuted by Nazi Germany for his Jewish heritage, he would come to understand the evolution of minerals from elemental to more complex forms. He was fascinated by olivine, and after the war he published a research paper on how complex organic molecules might have led to the origin of life on Earth, and "the ideas in that paper remained central to our efforts to understand how life came to be," Tyson says, as he asks us where that life might have taken root in the cosmos.

We embark upon a tour of the solar system, with Tyson identifying each by its planetary protection protocol number as endowed by NASA — an indicator of how likely it might be for a planet or moon to contain life, and how important it is to protect any possible forms of life there.

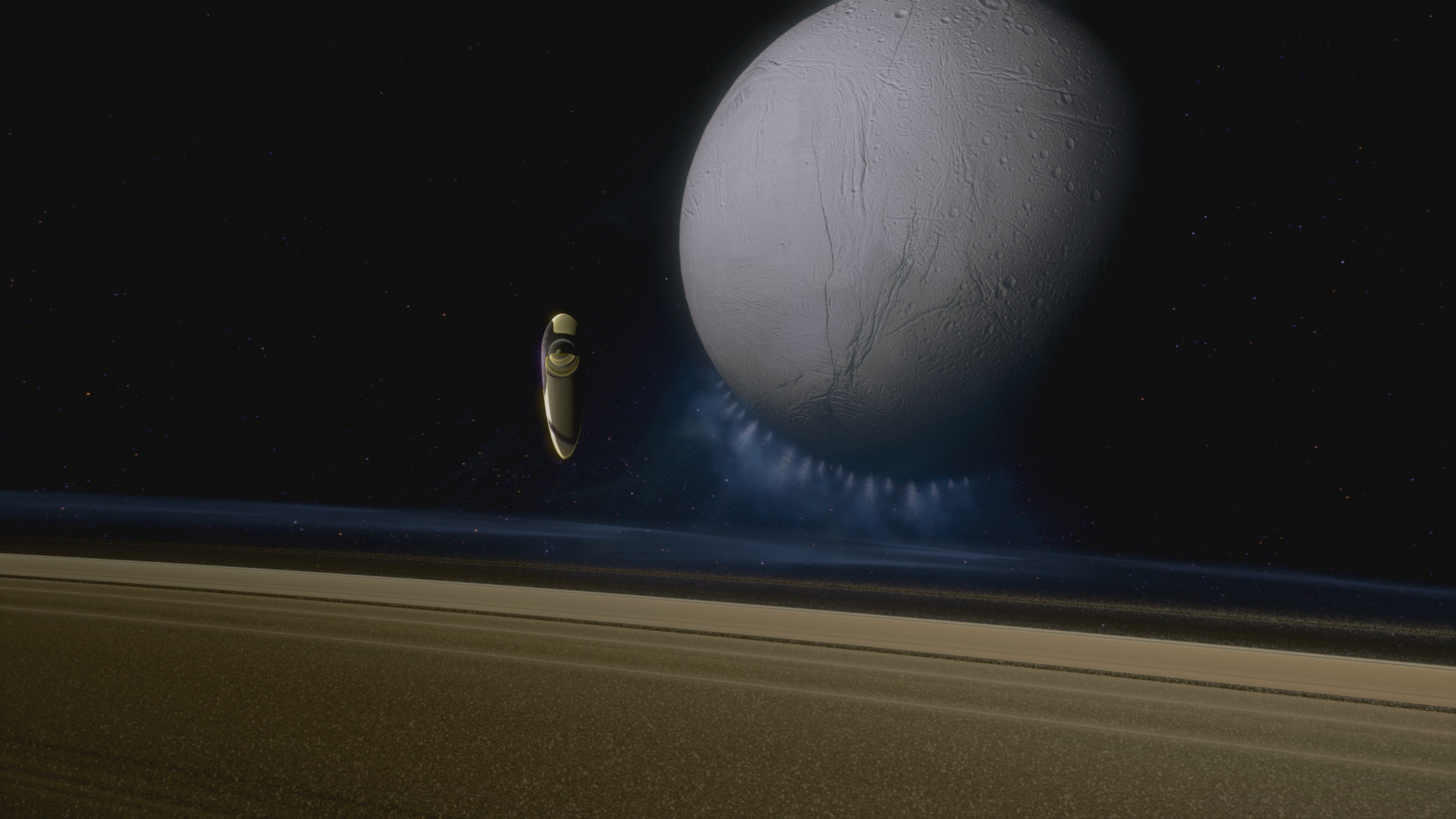

For example, Earth's moon, an airless wasteland, is classified as a "Category I" world and deserves little consideration with regard to damaging the ecosystem, according to NASA. Mars, on the other hand, is a "Category V" planet, with specific areas that deserve the highest protection we can manage — life may have existed there, and might still. The other two places in the solar system that warrant "Category V" protection are Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus.

Related: If we find life on Europa or Enceladus, it will be a '2nd genesis'

Enceladus, which NASA's Cassini mission studied for 13 years while orbiting Saturn, warrants further exploration, Tyson says, because scientists believe the icy moon could host life. He takes us below the icy crust and into the oceans — far deeper than any on Earth — where we see underwater towers of carbonate structures, another "lost city of life," one that might be hiding life-forms similar to those on the primordial earth. The pH of the water is similar to Earth's early oceans, as are other conditions. Has life had enough time to evolve here?

Tyson closes the episode with a typically eloquent thought: "We think we're the story, that we are the end-all and be-all in the cosmos. Yet for all we know, we're just the byproduct of geochemical forces, ones that are unfolding throughout the universe ... galaxies make stars, stars make worlds ... for all we know, planets and moons make life. Does that make life less wondrous? Or more?"

"Cosmos: Possible Worlds" premiered March 9 on the National Geographic channel, and new episodes will air Mondays at 8 p.m. EDT/9 p.m. CT. The series is also expected to run on the Fox television network this summer.

- Carl Sagan: Cosmos, pale blue dot & famous quotes

- Book excerpt: 'For Small Creatures Such As We' by Sasha Sagan

- Sasha Sagan dives into science, space and spirituality in new book

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rod Pyle is an author, journalist, television producer and editor in chief of Ad Astra magazine for the National Space Society. He has written 18 books on space history, exploration and development, including "Space 2.0," "First on the Moon" and "Innovation the NASA Way." He has written for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, WIRED, Popular Science, Space.com, Live Science, the World Economic Forum and the Library of Congress. Rod co-authored the "Apollo Leadership Experience" for NASA's Johnson Space Center and has produced, directed and written for The History Channel, Discovery Networks and Disney.