'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' episode 5 explores the 'cosmic connectome'

In the fifth episode of "Cosmos: Possible Worlds," host Neil deGrasse Tyson explores questions that have baffled scientists for centuries. "Can we know the universe?" he asks. "Are our brains capable of comprehending the cosmos in all of its complexity and splendor?"

"Our brain," Tyson elaborates, "remains almost as much of a mystery as the universe itself." Love, war, happiness, politics — everything we know and will know originate in the human brain. To try to answer these questions, Tyson takes us on a journey — as he so often does — through our cosmic past, beginning with early humans who believed our thoughts came from our hearts, not our brains, and who had little understanding of the mechanical failures which can occur in the brain that lead to devastating conditions like epilepsy.

Tyson then explores the work of Hippocrates, a physician of ancient Greece known as the "father of medicine," who wrote a code of ethics for doctors that is still used to this day. "The physician must investigate the entire patient, his diet and his environment. The best physician is the one who is able to prevent illness. Nothing happens without a natural cause." This is the thinking which revolutionized medicine in Greece 2,500 years ago, where it was believed physical ailments could be cured by appeasing the gods. "The idea that the ritual appeasement of one of the gods could bring about the cure for an epileptic seizure was magical thinking," Tyson says in the show, though the real magic was yet to come.

Related: 'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' takes us back into a universe of science

Paul Broca, a surgeon at the Bicêtre Psychiatric Hospital near Paris, France in the 19th century, would revolutionize his field through his humanist ideals and enlightened treatment of the insane and mentally unstable. Broca would go on to locate and connect a part of the brain and its specialized function: speech production. This region of the brain would become known as "Broca's area" in his honor.

Broca's own brain, along with the brains of mass murderers, master criminals and those with congenital abnormalities ended up in a jar on a shelf in the back storage room of a museum. Despite Broca's accomplishments in the study of the human brain, Broca too was "blinded by the prejudices that blinded his society," Tyson says. "His falling short of humanist ideals shows that even someone as committed to the free pursuit of knowledge as Broca could still be deceived by endemic bigotry."

Broca's prejudices reveal the ugly underbelly of anthropological and neurological studies, which often shed light on our worst traits and tendencies as human beings. "Society corrupts the best of us," Tyson says. He then poses the following question, one we could never hope to answer in our own lifetime, leaving us only to guess at its answer: "Which of the assumptions of our own age will be considered unforgivable by the next?"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Having explored the scientist who established the correlations between anatomy and function, Tyson turns his gaze upwards to the stars, pondering the intersection where physiology meets spirit. "What of the crackling energy of consciousness? What of the stuff our dreams are made of?" Tyson asks. He then turns our attention to our dreams, and how ancient Egyptians believed the starry night sky was the underbody of Nut, goddess of the sky. Dreams were ritualized as a form of worship, a means of transporting oneself to the afterlife to learn, to communicate with the gods or to learn what their future held.

Dreams were of such importance to the ancient Egyptians that the most faithful would make a pilgrimage to a temple, where they would dream in a state of fasted isolation. Prayers to specific gods might be written and then burned, in the hopes the smoke would deliver the prayer's message to the underworld. Ascribing meaning and significance to our dreams has been part of our makeup as humans from the beginning, and though modern scientists still don't know why we dream, we now know exhaustion and fatigue are part of our body's defense mechanism, a means by which it tells us to slow down before we injure ourselves.

This discovery comes from the 19th century inventor of neuroimaging, the Italian physiologist Angelo Mosso. Like ancient Egyptians, Mosso believed dreams had a material reality and could be recorded. Tyson takes us to the Manicomio di Collegno, a now-abandoned psychiatric hospital in Collegno, Italy that had previously served as a monastery. Like the Bicêtre Psychiatric Hospital we visited previously, the building's beautiful architecture betrays nothing of the "broken minds and shattered dreams" housed inside.

It was there that Mosso had his breakthrough and successfully recorded the dreams of a young boy, Giovanni Thron, who suffered from epilepsy and severe brain damage. "On that snowy night, Angelo Mosso gave the brain its first pen to write with," Tyson says, standing in a room which may very well resemble the one where a young Giovanni might have been observed by Mosso. Somberly, Tyson recounts that just three short nights after Mosso successfully recorded the "faint signature" of Giovanni's thoughts, the boy died of anemia, though not before leaving his permanent mark in the history of neuroscience.

Our journey continues as Tyson introduces us to an unlikely hero; Hans Berger, a German psychiatrist who dedicated his life to the aim of proving that psychic energy was real. Though Berger never succeeded in demonstrating that one could harness the power telepathy and other psychic abilities, he did invent an apparatus which could record the brain's signals — the electroencephalograph, better known as the EEG. In allowing us to interpret these signals, the EEG made it possible to diagnose neurological diseases, like epilepsy. Ironically, Berger himself sunk into a deep depression having never found proof that psychic energy was real and hung himself, leaving behind a gift that would transform medicine for years to come.

Having looked to the past, and how just 100 years after Mosso recorded Giovanni's dream, the brainwaves of a woman newly fallen in love were included in the Voyager spacecraft's interstellar message. "Of all the billions of species that have ever lived on Earth," Tyson says, "why us and no other?" He then brings us face-to-face with flatworms and microbes with which we share a common gift that brings us "closer to the stars" — brains.

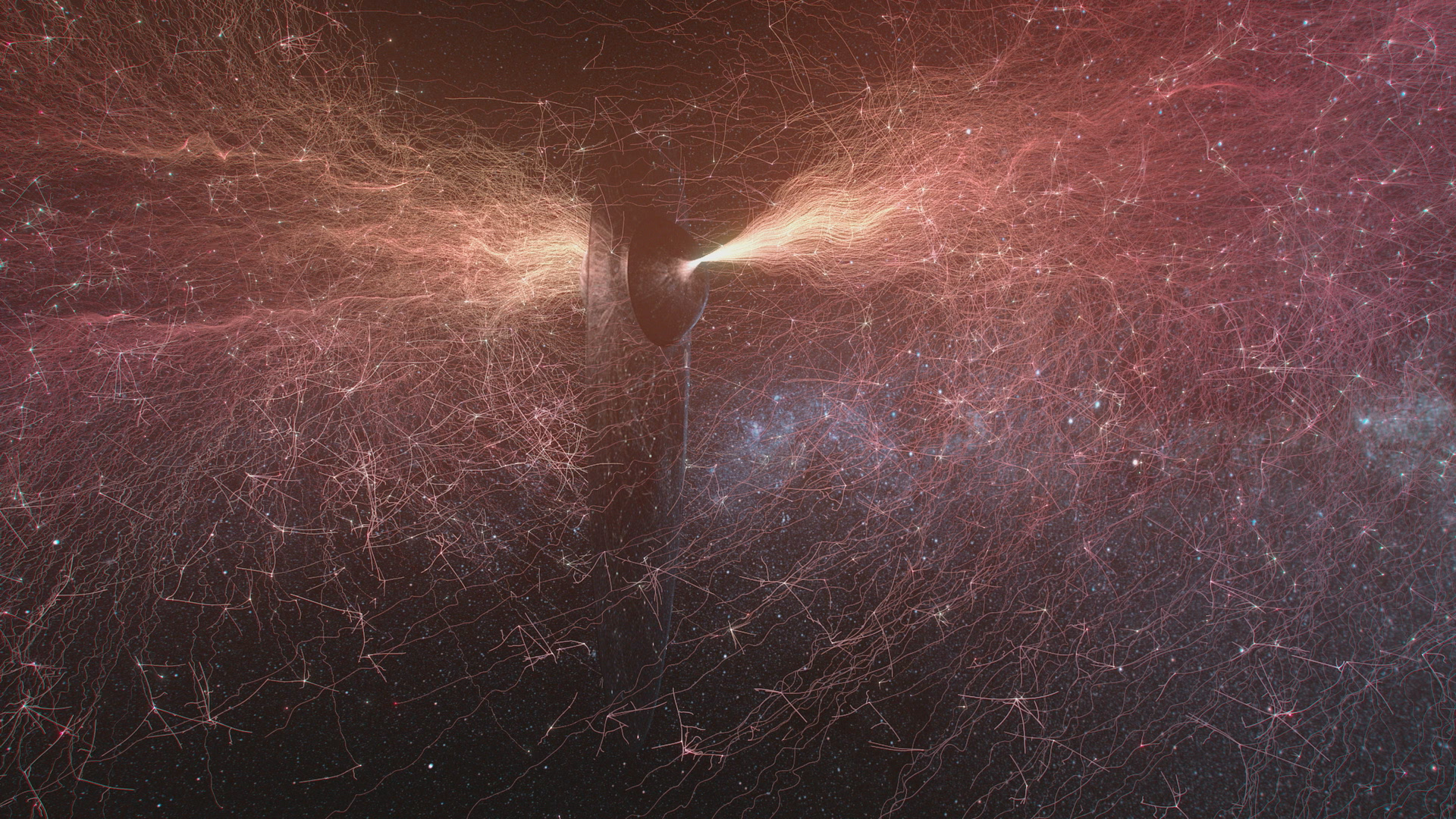

Our brains, Tyson concludes, are as mysterious and vast as the cosmos itself. "Can we know the universe, and will it ever come to know us?" While we cannot fully know even a single grain of salt, our brains are more complex and magnificent than any man-made machine. The cosmos inside each of us, what Tyson calls an "unknown and solitary sea," is the final area of research Tyson calls our attention to. Our connectome, unique to each individual, contains the wiring diagram of our thoughts, dreams, and fears and may contain the secrets to unlock a greater journey of exploration.

"Cosmos: Possible Worlds" premiered March 9 on the National Geographic channel, and new episodes will air Mondays at 8 p.m. EDT/9 p.m. CT. The series is also expected to run on the Fox television network this summer.

- 5 mind-bending facts about dreams

- One 'strange' organ: astronauts explain the wonders of the human brain

- Neil deGrasse Tyson's 'Cosmos' sets an example for science educators (op-ed)

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Melissa is a former contributor to Space.com who covered Space Movie and TV, specifically Neil deGrasse Tyson's "Cosmos: Possible Worlds." She also was featured in Ad Astra, the official magazine of the National Space Society, penning, "REACHING FOR THE STARS," Education Is the First Step Toward Space Settlement and "MANY HAPPY RETURNS," Returns on Investment from Space Education