Neil deGrasse Tyson ponders the fate of planet Earth in 'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' finale

Science has been the guiding star which we human beings have followed in our quest to understand the world around us and decipher our future. Often, science offers us solutions to our most vexing questions, and in our most trying times.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, paying homage to host of the original "Cosmos," Carl Sagan, opens the final episode of "Cosmos: Possible Worlds" with a reflection on science and those who help us understand it. "We all feel the weight of the shadows on our future," Tyson says, "but in another time, every bit as ominous as our own, there were those who could see a way through the darkness to find a star to steer by."

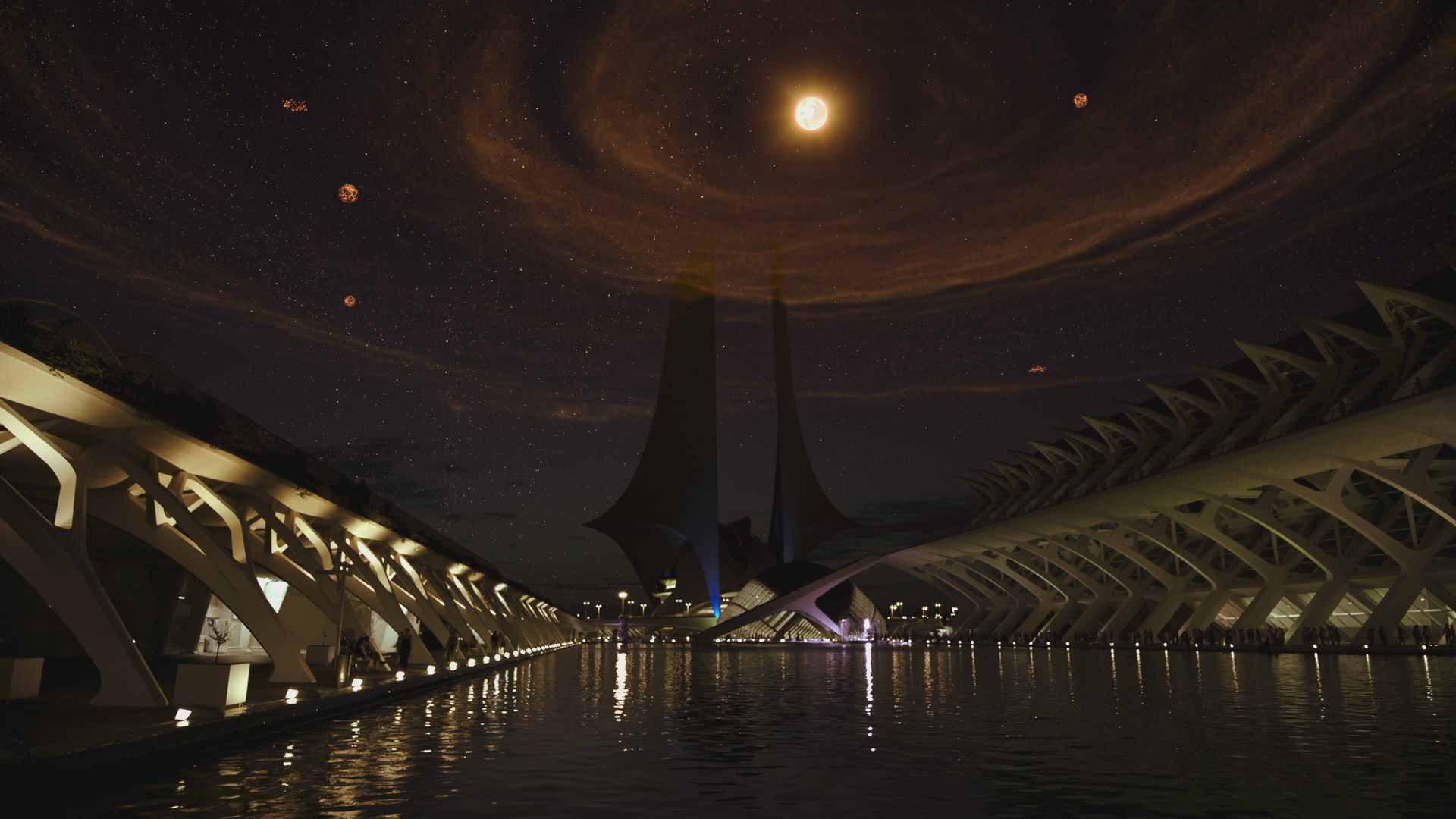

Sagan's own romance with science began at the 1939 New York World's Fair. "I was a child in a time of hope," he wrote of his upbringing; World War II had begun just six months prior to the opening of the fair in Flushing Meadows. A montage of black-and-white photos of the event feature structures called the Trylon and Perisphere, a massive spire-shaped building connected to a giant sphere, which embodied the fair's theme, "The World of Tomorrow." The Perisphere housed a diorama of a utopian city, which could be viewed from above via a moving sidewalk.

Related: Carl Sagan's legacy, from the 'Pale Blue Dot' to interstellar space

The fair was "where the future became a place," Tyson says, and the forward-looking visions presented there inspired future scientists and engineers like Sagan.

Tyson thinks back on his own experience as a young boy attending the 1964 New York World's Fair, which took place when the world was facing a different set of problems — the Cold War was in full freeze. Geopolitical tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States were at a peak due to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which occurred just two years prior.

Despite these bleak conditions, the 1964 New York World's Fair was a symbol of hope for a better future, "when science and technology had been refocused on human hopes and dreams," Tyson says.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

He recalls riding the "Tyson Comet" into the fair; his father was a key administrator for New York City at the time, and the monorail had been named after him for the day. The Unisphere, a steel representation of the Earth commissioned especially for the event in 1964, showed our planet as just one piece of a much larger universe, one we had yet to explore. Tyson recalls it vividly.

Some of the promises made at the New York World's Fair remained unfulfilled, Tyson notes, while others have exceeded anything we might have thought possible.

The Mercury, Gemini and Apollo spacecraft NASA brought to display, for example, all offered an optimistic dream of the future. But in the case of the Mercury and Gemini spacecraft, which carried NASA's first astronauts into space, the rockets that would boost them into the vast blackness were the same types of vehicles that could launch weapons of mass destruction.

Looking forward, Tyson envisions another New York World's Fair, in a period when not only will our species have "found a way to avert the worst consequences of climate change," but we will also have declared "our ambition for the kind of greatness that lives in harmony with our fellow earthlings," he says.

At this point in the episode, we revisit the baby whose narrative began last week in episode 12; she is now a young girl in the year 2029 and shows us her own reaffirming vision of the future in a drawing titled "How the Earth Got Well."

fIn 2033, for example, the girl imagines that humanity has achieved first contact with blue whales and successfully translated their songs. The year 2055, we see quantum physics confirming the existence of multiple realities.

The subsequent decades see the Amazon rainforest tripling in size, no new entries on the endangered species list, the last internal combustion engine donated to a museum, the growth of the polar ice caps, the cleansing of the oceans, the ozone layer fully restored, and finally the recovery of Earth from the industrial revolution, which kickstarted the current global warming trend, by 2075.

We fast-forward ten years to the 2039 New York World's Fair, when the girl is a young woman with a child and family of her own. Tyson takes us on a tour of the fair, beginning with the "Pavillion of the Searchers," where the "greatest heroes in the history of science" answer every question imaginable for fair attendees.

In this imagined world, we've found a way to recreate these scientists' neural networks: their connectome. "Imagine a world where the still unfolding story of the universe was told to every child, as naturally as we tell them our nursery rhymes and fairytales," muses Tyson.

From there, we visit the "Pavillion of the Fourth Dimension," where Tyson's "cosmic calendar" (a timeline of the entirety of our universe's existence condensed into a calendar year) makes its final appearance.

Here, fair goers can visit any moment, anyplace in the universe's 14-billion year history of evolution. Our narrative follows the young woman and her family as they visit the moon's surface on July 20, 1969 — the date of the Apollo 11 moon landing and the first time in history humans set foot on another world. Centuries of gazing at the moon and wondering about other worlds beyond Earth has helped humanity appreciate "life's genius," Tyson says.

Tyson likens life to an escape artist, who "having found every niche on Earth, even ventured to the moon." Life itself has survived five mass extinction events, like the asteroid impact that wiped out about 75% of all species on Earth, including the dinosaurs.

"Life finds a way into the future," Tyson says as he describes how in his imagined future, we've found a way to deal with the consequences of our more brutal past, like landmines and indiscriminate pollution.

These are "shameful artifacts of our technological adolescence," he says, but in the future humans will hopefully have found a way to deal with its self-imposed problems, like the massive amounts of waste from nuclear power plants and weapons, as well as toxic garbage from electronic toys like lead, cadmium, and beryllium.

In Tyson's ideal future, bioremediation — a waste management technique that relies on microorganisms like yeast — will neutralize and degrade these pollutants and clean up the environment.

Against the backdrop of this possible future, Tyson asks us to think about how we can avoid repeating these mistakes. "Nature offered us a second chance; a shot at undoing the damage we'd done; but how do we keep from doing it again?"

Related: Top 10 emerging environmental technologies

To that end, Tyson takes us to the "Pavillion of Lost Worlds," where we remember civilizations long gone, like the wealthy and vibrant Tartessians who lived on the Iberian peninsula in the first millennium BC and who had their own language and culture. Very little survives of the Tartessians, much like the nameless settlers who around that same time period lived in modern-day Nigeria in a place called Nok. Their engineers forged new ways to work with iron, yet we have almost nothing of theirs to study. Despite having few surviving remnants of their civilization, "they were as real as we are — their moment as real as ours," Tyson says.

Finally, we arrive at "The Pavillion of Worlds Still to Come." In this imagined future, we search for other worlds, home to other forms of intelligent life. Tyson asks us to picture an "Encyclopedia Galactica," a constantly evolving open-source reference work containing every world and star in existence. Together, we skim its entries and come across an exoplanet with a civilization far more advanced than ours.

These alien beings disassemble other planets in their system and reassemble them around their world in a ring, to provide more room and resources. Such a planet has a high chance of survival: 99% per one million years, Tyson says. Another planet, whose civilization depleted their fuel sources and now depends on the solar power produced by a red dwarf, only has a 33.9% chance of survival per one thousand years.

We arrive at our own planet and Tyson wonders how we'd define our entry in this great "cosmic encyclopedia." In these final moments, we return to the questions asked at the beginning of the series, about how we can understand our universe. How would our "planetary dossier" look to an outsider? Our probability of survival according to this fictional entry is a mere 50% per 100 years. Turning to a more optimistic tone, Tyson offers us a way to improve those odds: "It's about taking what science is telling us to heart."

In the final scene of the episode, we witness the formation of stars, which are born from the remnants of their deceased stellar predecessors. In the vast darkness, the earliest stars came together to form galaxies, and in one of those galaxies, our planet bore intelligent life.

Our species and everything on our planet is made of matter, or "star stuff," as Tyson calls it, that originated from great stars, hundreds of times the mass of the sun. Our species is but one small branch on the "Tree of Life," Tyson concludes, and our fate is tied to those of our fellow earthlings.

Tyson concludes the series with a hopeful forecast of mankind's future and legacy: "Slowly, we learned to read the book of nature to learn her laws, to nurture the tree, to become a way for the cosmos to know itself and to return to the stars."

That wraps up this season of "Cosmos: Possible Worlds," which premiered on the National Geographic Channel in March. The show will be reprised on the Fox television network this summer.

- 'Cosmos' with Neil deGrasse Tyson returns on Fox, NatGeo Channel

- 'I want the solar system to become our backyard,' Neil deGrasse Tyson says

- Forged in fire: Earth's past and future explored in 'Cosmos: Possible Worlds'

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Melissa is a former contributor to Space.com who covered Space Movie and TV, specifically Neil deGrasse Tyson's "Cosmos: Possible Worlds." She also was featured in Ad Astra, the official magazine of the National Space Society, penning, "REACHING FOR THE STARS," Education Is the First Step Toward Space Settlement and "MANY HAPPY RETURNS," Returns on Investment from Space Education