Could the moon ever be pushed from orbit like in 'Moonfall'?

In the movie "Moonfall," a wayward moon threatens Earth.

The moon has been Earth's close companion for billions of years, and while our view of its shape and size varies somewhat as it orbits our planet, it remains a constant presence in the sky. But could that change?

In the 2022 movie "Moonfall" (Lionsgate, released on Feb. 4), a mysterious force ejects the moon from orbit and propels it on a collision course toward Earth, with a planet-smashing impact looming in just a few weeks. (Caution, spoilers ahead.) When confronted with this high-stakes and over-the-top disaster scenario, the film's characters scramble to save the planet; in doing so, they learn that our natural satellite isn't so natural after all.

The notion of the moon as an artificial megastructure that was built billions of years ago by intelligent aliens is firmly rooted in the realm of science fiction. But is there any naturally occurring object in space that could truly push the moon from its orbit? With tens of thousands of asteroids and comets whizzing around the solar system, could a collision with a big enough rock ever turn the moon into a projectile that could crash into Earth?

Related: What if the moon disappeared tomorrow?

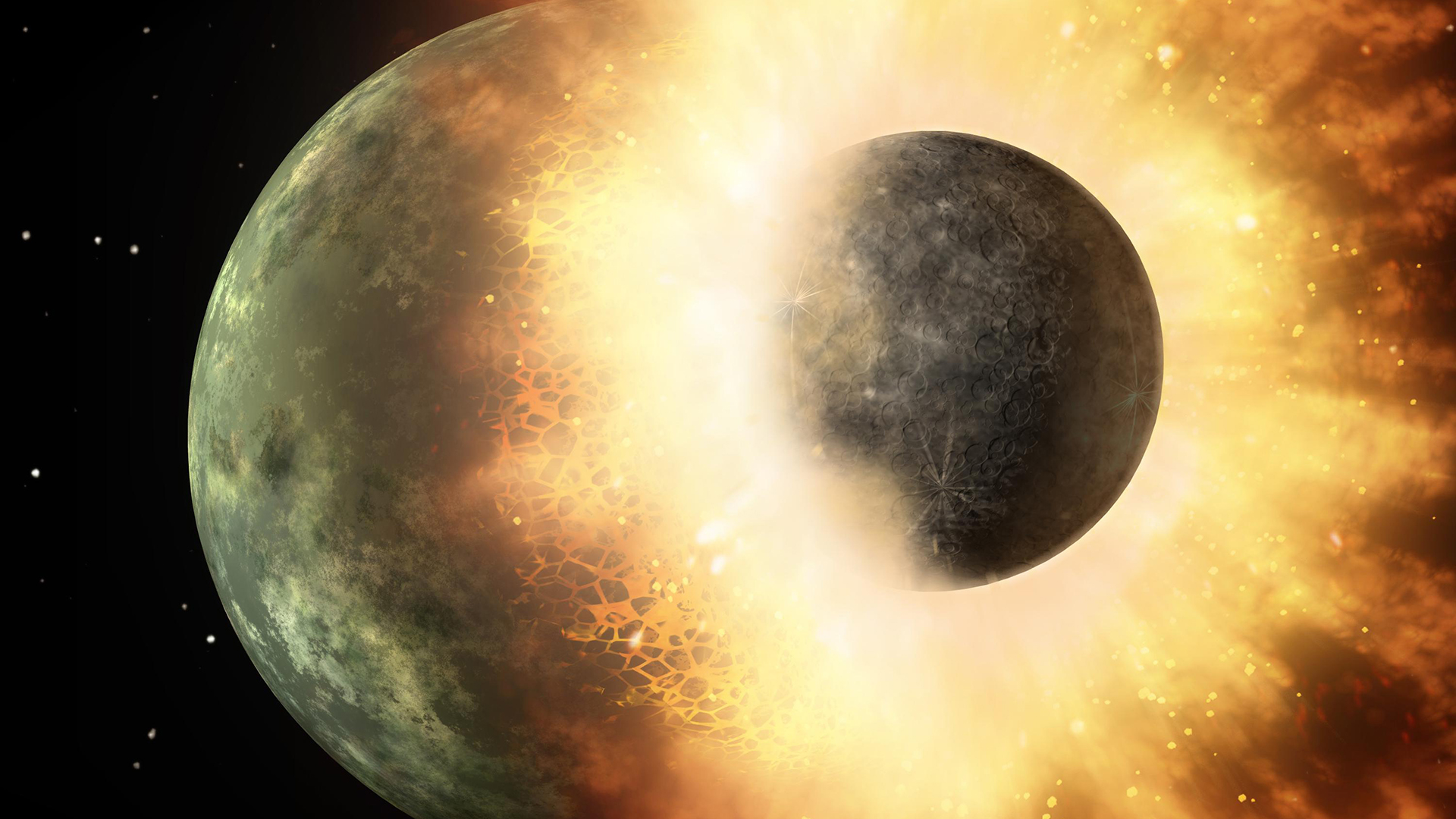

Our moon is a solid, rocky body surrounded by a very thin layer of gases known as an exosphere, and the natural satellite formed around the same time Earth did, about 4.5 billion years ago. A widely accepted hypothesis suggests that the moon emerged from rocky debris after a massive impact between a young Earth and a smaller protoplanet: a hypothetical object called Theia, according to NASA. Another impact hypothesis proposes that both the moon and Earth formed after the collision of two bodies, each five times the size of Mars, NASA says.

The moon is located about 239,000 miles (385,000 kilometers) from Earth and has an estimated mass of more than 1.62 x 10^23 pounds (7.35 × 10^22 kilograms).. It's about one-fourth Earth's size; if Earth were the size of a nickel, the moon would be about the size of a pea, according to NASA.

Images of the moon show that its surface is pocked with craters of various sizes, made by past impacts. But most of those were made billions of years ago, when there was a lot more debris zipping through the solar system, said Paul Chodas, manager of the Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech in Pasadena, California. Most of the planet-forming rocky debris that once filled the solar system has long since dissipated, "so the number of impacts has gone way down now — there's a lot less material to impact the Earth or the moon," Chodas told Live Science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

CNEOS identifies and tracks near-Earth objects (NEOs) such as asteroids and comets, to determine if they pose a threat to Earth, the moon or our other cosmic neighbors, according to the center's website. To date, CNEOS is following about 28,000 NEOs — objects that approach Earth within 1.3 astronomical units (120.9 million miles, or 194.5 million km).

"We check for collisions between any planet and asteroid, and we check for collisions on the moon," he said. In general, asteroid collisions with the moon are much less likely than collisions with Earth, because our planet is a more massive target with stronger gravity. A wayward space rock that looped into our cosmic neighborhood would therefore be pulled toward Earth rather than toward the moon, Chodas explained.

Size also matters when scientists are considering the risk posed by a hurtling asteroid. For a NEO to be classified as a threat to Earth, it has to measure at least 460 feet (140 meters) in diameter, according to NASA. And for an asteroid impact to affect the moon's orbit, the asteroid would have to be at least as big as the moon itself, Chodas said.

"The moon is big, so it would have to be a huge object that would have to hit it at high speed," he said. "You'd have to hit it with something that's hundreds and hundreds of miles in diameter."

Related: What does it take to be a moon?

Luckily for us (and for the moon), none of the known asteroids in the solar system is anywhere near moon-size. The biggest known asteroid is about 70 times less massive than the moon, and it orbits between Mars and Jupiter in the main asteroid belt, about 112 million miles (180 million km) from Earth, according to NASA.

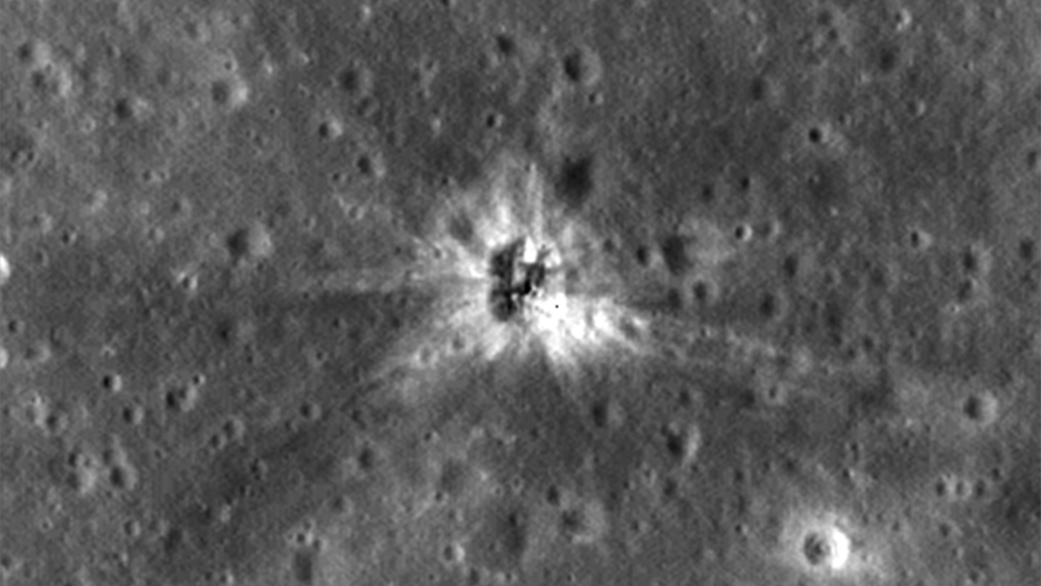

That might rule out the possibility of an asteroid from the solar system dislodging the moon, but what about a human-made object? As it happens, a spent SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket booster stage that launched in 2015 is currently on a crash course with the moon and is expected to smash into it in March 2022, Live Science previously reported.

The rocket segment, which weighs about 4.4 tons (4 metric tons), ran out of fuel after the orbital placement of the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), a satellite for monitoring Earth's climate and solar storms and a joint project between NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The now-empty booster will be traveling at approximately 5,771 mph (9,288 km/h) when it strikes the far side of the moon on March 4 at 7:25 a.m. EST, and the impact should produce a crater measuring about 65 feet (20 meters) in diameter, The New York Times reported.

There's no danger of the crash affecting the moon's orbit; nevertheless, CNEOS is closely monitoring the rocket's trajectory, despite not normally tracking artificial objects in space, Chodas told Live Science.

"We're doing some calculations especially for this object," he said. "This one is of interest to the LRO spacecraft [NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter], which is orbiting the moon and could take a picture of the crater, so they'd like to know where it's going to hit. And we can work out the predictions of where to look and where that crater will be a month from now."

So, the next time you look up at the moon in the night sky, you can take comfort in the thought that it's not going anywhere anytime soon.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.