Black holes that form in 'reverse Big Bang replays' could account for dark energy

"This is very likely to bring us closer to discovering the true nature of dark energy. Perhaps it will also bring us closer to an understanding of the true nature of black holes"

Scientists have strengthened the potential connection between dark energy and black holes. New research suggests that as more black holes were born in "little Big Bang reverse replays" in the 14.6 billion-year-old cosmos, the strength of dark energy grew to dominance and continues to change to this day.

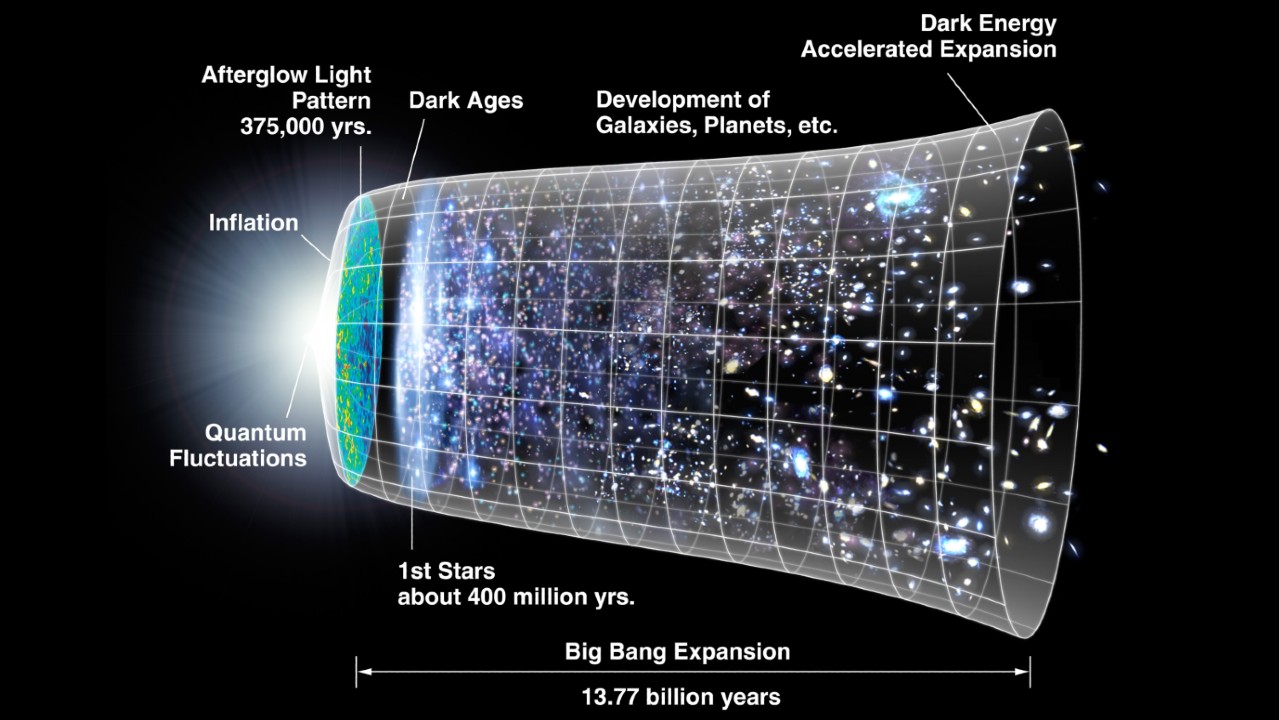

Dark energy is the placeholder name given to the mysterious force driving the acceleration of the universe's expansion in its current epoch. It is troubling because scientists have no idea what dark energy is, yet it dominates our universe, accounting for around 70% of the cosmic matter/energy budget. This wasn't always the case, however. Prior to the dark energy-dominated epoch, matter and gravity had ruled the universe and had succeeded in slowing its initial Big Bang-driven expansion to a near stop. Dark energy then staged its cosmic coup around 5 billion years ago, "hitting the gas" on the expansion of the universe again. The problem is that no one knows where it came from or how that switch from matter to dark energy happened.

To address this mystery, a team of scientists has been asking themselves where in the modern-day universe is gravity as strong as it was at the beginning of the universe? The answer is only at the heart of black holes. Thus, the team determined that black holes could be "cosmically coupled" to dark energy.

"According to the cosmological coupling hypothesis, black holes are coupled to the expanding universe and are filled with dark energy that grows as the universe expands," team member Gregory Tarlé, professor of physics at the University of Michigan, told Space.com. "This new development provides confirming evidence that cosmologically coupled black holes may very well be the dark energy of the universe."

Tarlé says that this could be because when a black hole forms during the death and gravitational collapse of another black hole, it is akin to the Big Bang running in reverse. During this process, the matter of the massive star that births a black hole would become dark energy during its complete gravitational collapse.

If black holes contain dark energy, the team theorizes that they can couple with the fabric of the universe and drive its accelerating expansion. They don't yet have the details of how this is happening, but they have evidence that it is indeed happening.

"This new development provides confirming evidence that cosmologically coupled black holes may very well be the dark energy of the universe," Tarlé said. "This is very likely to bring us closer to discovering the true nature of dark energy. Perhaps it will also bring us closer to an understanding of the true nature of black holes."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The heart of the mystery lies at the heart black holes

This is the second time the team has published research focusing on the cosmological coupling between black holes and dark energy.

"The first study we published in February 2024 showed the impact of the expanding universe on the growth of supermassive black holes in passively evolving elliptical galaxies," Tarlé said. "If all black holes grew in this way, they could collectively account for the density of dark energy in the universe today."

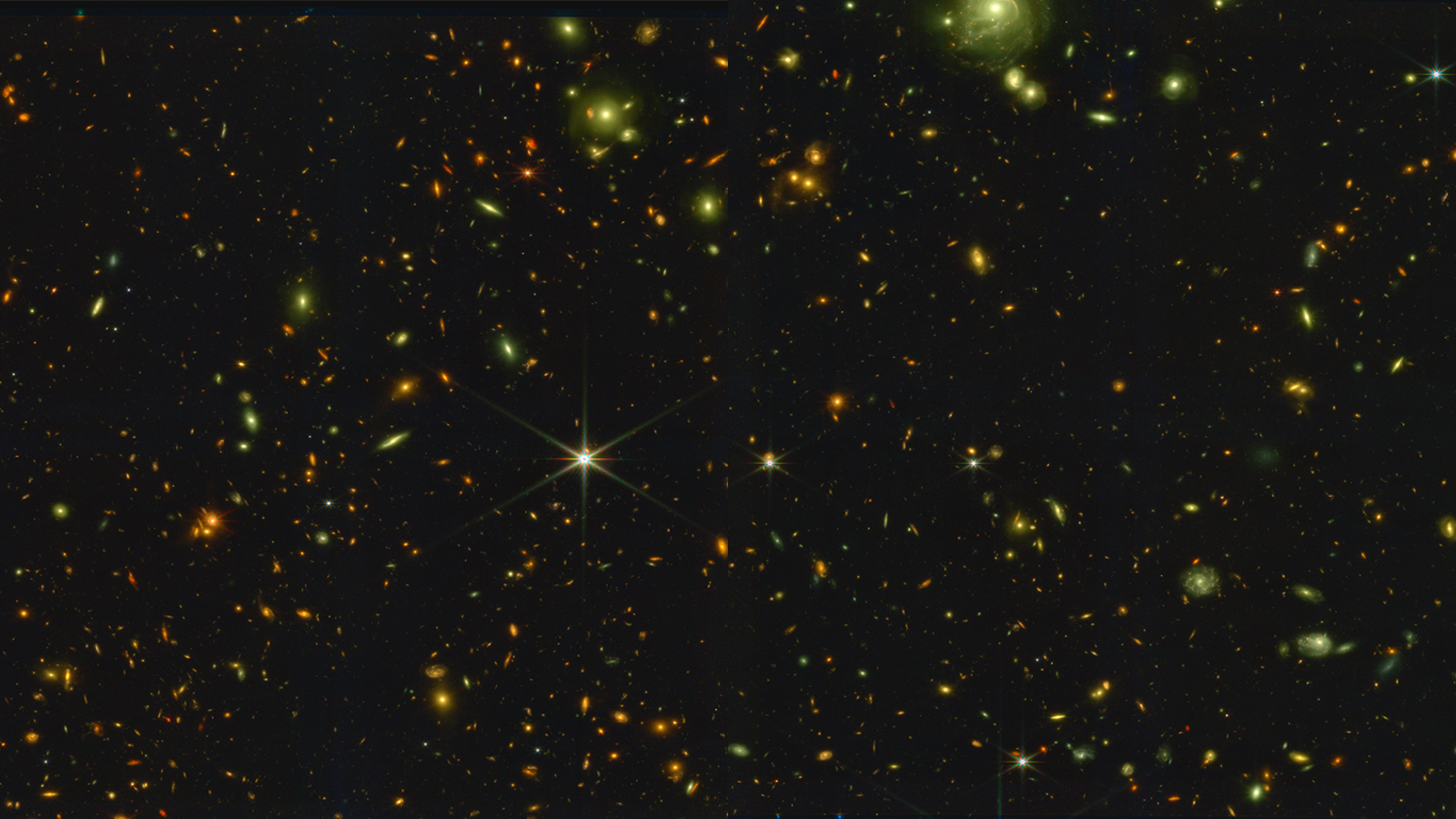

For this new investigation, they turned to data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). Composed of 5,000 robotic eyes mounted on the Mayall telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory. DESI surveys tens of millions of galaxies and quasars to build a 3D map spanning the universe out to a distance of 11 billion light-years.

DESI made waves with its first year of data from its five-year program by suggesting that the density of dark energy in the universe is changing.

"It is generally believed that dark energy is a property of space and that it is, therefore, uniform and constant in density. DESI has just provided tantalizing evidence that the dark energy density is not constant - that it is changing in time," Tarlé said. "This coupling theory provides a possible physical mechanism for this change."

The team compared the DESI data concerning the change in dark energy to the number of black holes born in the deaths of massive stars across cosmic history. This showed that as more black holes were created, the universe's content of dark energy increased in lockstep. This implies that a connection between dark energy and black holes is at least plausible.

By showing the change in the density of dark energy suggested by DESI's first year of data, which can be accounted for by black holes produced from heavy stars around the peak of star formation, the team has some experimental validation of their theory.

"Showing how the growth of dark energy density tracks the production and growth of black holes in the expanding universe is an independent observation that complements the observation of the growth of black holes with the expansion of the universe," Tarlé continued.

While the Michigan University researcher and his colleagues aren't yet ready to explain how dark energy and dark matter are connected, Tarlè is prepared to speculate for Space.com.

"In the very early universe, when gravity was very strong, a form of dark energy caused the universe to exponentially inflate. Through some unknown process, this energy was transformed into the matter of the universe today," Tarlè explained. "It is conceivable that, in the center of black holes, the only place in the present universe where gravity is as strong as it was during inflation, matter gets transformed into dark energy by the reverse process."

The beauty of this theory, Tarlè said, is that it not only helps to explain dark energy and where it emerged from but also helps solve a lingering problem in black hole science.

Currently, at the heart of black holes, in theory at least, there exists a singularity, a point where the equations of Einstein's theory of gravity and general relativity go to infinity and, thus, where all physics breaks down. The cosmological coupling of dark energy and black holes does away with this singularity.

"Our theory has the added benefit of providing a mechanism where a central singularity may be avoided," Tarlè added. "Einstein never believed in the singularity at the center of black holes and felt that this represented a failure of his theory."

Tarlé explained that this work could grow down a series of possible avenues. He added that there are many "next steps" the team could take. Among them is seeing if their results hold up when DESI releases its next 3 years of data, which is expected to drop within several months.

The researchers will also attempt to understand the distribution of cosmologically coupled black holes in the universe and work on an "interior solution" for cosmologically coupled black holes.

"Fundamentally, whether black holes are dark energy, coupled to the universe they inhabit, has ceased to be just a theoretical question," Tarlé concluded. "This is an experimental question now."

The team's research was published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics on Monday (Oct. 28).

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Unclear Engineer While I support the logical exploration of concepts such as this one, I think the way the article described the evidence for it is awfully weak.Reply

The closest it comes to make a coherent argument for the concept is the statement "s more black holes were created, the universe's content of dark energy increased in lockstep." Of course there is an increase of black holes over time, as they are formed by the evolution of large stars over time. And, we currently conceptualize "dark energy" as increasing with time, if only because we postulate that it is not diminished by the expansion of the universe that we observe. So, a rough correlation is expected, but that has no implications for cause and effect relationships.

So, the whole concept hinges on the idea of some tighter correlation, implied by using the word "lockstep". The article implies that DESI data shows that dark energy is not uniform, and is correlated in 'Lockstep" with black hole formation, implying differences in black hole formation rates correlate with non-uniform dark energy density. That is what should have been described in much more detail for readers. How is this data acquired? How is it interpreted? What exactly are the correlated parameters? How strong is the correlation? -

danR Reply

I think the article is adequate for its purpose. Those who want to enquire further can turn to the papers themselves. Whether there is a causal link in the correlation suggested by the DESI data is a matter for the academic physics community at large.Unclear Engineer said:The article implies that DESI data shows that dark energy is not uniform, and is correlated in 'Lockstep" with black hole formation, implying differences in black hole formation rates correlate with non-uniform dark energy density. That is what should have been described in much more detail for readers. How is this data acquired? How is it interpreted? What exactly are the correlated parameters? How strong is the correlation? -

danR Nice to see a concept that removes the 'need' for singularities altogether, although it isn't the only one. Time will tell whether the BH-DE idea is falsified with further evidence, or else rises to the level of "theory".Reply -

Helio The discovery of DE goes back to the late 1990's observations of Type 1a SN, which revealed the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate. Some sort of energy is forcing our universe in a way that accelerates it. It's a mystery what it might be.Reply

But before Einstein, a universe that includes matter will collapse, though Newton suggested an infinite universe would prevent any collapse since there would be not c.g. (center of gravity) to give it place to collapse to.

As the universe expands, the gravitational force becomes weaker, thus a residual and repulsive force of energy (DE) would become increasingly larger relative to the weaking gravitational force. This assumes DE doesn't get weaker itself with expansion, of course. No one knows what DE is so we just play with the observations, for now, that suggest this is the case.

I don't see how the researcher's statement makes a lot of sense. "In the very early universe, when gravity was very strong, a form of dark energy caused the universe to exponentially inflate. Through some unknown process, this energy was transformed into the matter of the universe today,"

1) It states DE has different forms. That's an odd claim.

2) it states "the matter of the universe" comes from DE. We know high energy densities can produce matter in places like particle colliders (e.g. CERN) and in the cores of all stars. No DE is required, apparently.

It seems a little odd too that we have such great isotropy (1 part in 100,000) in the CMBR as predicted, and without some sort of uniform distribution of BHs.

There are other issues I have as well. Perhaps I'm misjudging the work, but it sounds like more metaphysics than physics. -

Helio Reply

But I didn't see a link, though I found one here DESI.danR said:Those who want to enquire further can turn to the papers themselves. Whether there is a causal link in the correlation suggested by the DESI data is a matter for the academic physics community at large.

From the link, "The results are in general agreement with the current best cosmological model (Lambda CDM), which takes into account the roles of dark energy and dark matter."

So we may not need something new.

On the other hand, the link states, "But as noted by DESI Director Michael Levi, “we’re also seeing some potentially interesting differences that could indicate that dark energy is evolving over time. Those may or may not go away with more data, so we’re excited to start analyzing our three-year dataset soon.”

It's unclear what's being suggested. If DE is simply increasing relative to the gravitational field, then acceleration would be expected, so perhaps they mean something else, though I suspect this may not be the case. The study of the Lyman-Alpha Forest would reveal acceleration changes, which I think is what they are finding. -

Unclear Engineer The paper itself is pretty opaque to the average reader, even with an extensive STEM background. See https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1475-7516/2024/10/094/pdf .Reply

As Billslugg says, we need a bartender-level explanation of the basic evidence. -

Atlan0001 Ahem, if I may!Reply

https://forums.space.com/threads/from-a-drop-of-water.61072/page-36#post-607505 -

Helio Reply

:) Yeah and first let's have a round of double BHs and tonic. ;)Unclear Engineer said:The paper itself is pretty opaque to the average reader, even with an extensive STEM background. See https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1475-7516/2024/10/094/pdf .

As Billslugg says, we need a bartender-level explanation of the basic evidence. -

DrRaviSharma I am not an expert on Dark Energy Research. But I have stated in my yet to be published but accepted for publication article that DE is likely to be related to the disappearence of Matter Energy into Dark Matter.Reply

Therefore as humbly submitted even after a year of acceptance I awit its publication mostly about DM.

Regards.

Dr Ravi Sharma -

finiter New ideas should be welcomed and evaluated. The singularity can be removed easily by assuming gravity is finite. That is, gravitational force that a body can exert has a limit, just like the speed-limit. If the universe is expanding due to the initial heat energy, which gradually changes to speed, then the expansion will be accelerating, and that eliminates the need of dark energy. These possibilities have not been considered so far.Reply