Scientists tap into 2 new quantum methods to catch dark matter suspects

"We are using quantum technologies at ultralow temperatures to build the most sensitive detectors to date."

The hunt for dark matter is about to get much cooler. Scientists are developing supercold quantum technology to hunt for the universe's most elusive and mysterious stuff, which currently constitutes one of science's biggest mysteries.

Despite the fact that dark matter outnumbers the amount of ordinary matter in our universe by about six times, scientists don't know what it is. That's at least partly because no experiment devised by humanity has ever been able to detect it.

To tackle this conundrum, scientists from several universities across the U.K. have united as a team to build two of the most sensitive dark matter detectors ever envisioned. Each experiment will hunt for a different hypothetical particle that could comprise dark matter. Though they have some of the same qualities, the particles also have some radically different characteristics, thus requiring different detection techniques.

The equipment used in both experiments is so sensitive that the components have to be chilled to a thousandth of a degree above absolute zero, the theoretical and unreachable temperature at which all atomic movement would cease. This cooling must happen to prevent interference, or "noise," from the world corrupting measurements.

Related: 'Immortal stars' could feast on dark matter in the Milky Way’s heart

"We are using quantum technologies at ultra-low temperatures to build the most sensitive detectors to date," team member Samuli Autti from Lancaster University said in a statement. "The goal is to observe this mysterious matter directly in the laboratory and solve one of the greatest enigmas in science."

How dark matter has left scientists out in the cold

Dark matter poses a major issue for scientists because, despite making up about 80% to 85% of the universe, it remains effectively invisible to us. This is because dark matter doesn't interact with light or "everyday" matter — and, if it does, those interactions are rare or very weak. Or perhaps both. We just don't know.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, because of these characteristics, scientists do know dark matter can't be composed of electrons, protons and neutrons — all part of the baryon family of particles that compose everyday matter in things like stars, planets, moons, our bodies, ice cream and next door's cat. All the "normal" stuff we can see.

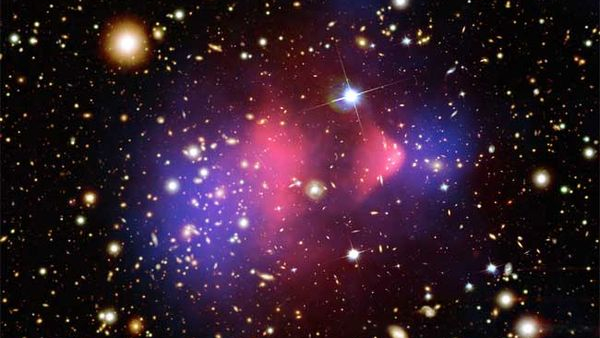

The only reason we think dark matter exists at all, in fact, is that this mysterious substance has mass. Thus, it interacts with gravity. Dark matter can influence the dynamics of ordinary matter and light through that interaction, allowing its presence to be inferred.

Astronomer Vera Rubin discovered the presence of dark matter, previously theorized by scientist Fritz Zwicky, because she saw some galaxies spinning so fast that if their only gravitational influence came from visible, baryonic matter, they would fly apart. What scientists really want, however, isn't an inference but rather a positive detection of dark matter particles.

One of the hypothetical particles currently posited as a prime suspect for dark matter is the very light "axion." Scientists also theorize dark matter could be composed of more massive (still unknown) new particles with interactions so weak that we haven’t observed them yet.

Both axions and these unknown particles would exhibit ultraweak interactions with matter, which could theoretically be detected with sensitive enough equipment. But two primary suspects mean two investigations and two experiments. This is necessary because current dark matter searches usually focus on particle masses between 5 times and 1,000 times the mass of a hydrogen atom. That means, if dark matter particles are lighter, they may be getting missed.

The Quantum Enhanced Superfluid Technologies for Dark Matter and Cosmology (QUEST-DMC) experiment is devised to detect ordinary matter colliding with dark matter particles in the form of weakly interacting unknown new particles that have masses of between 1% and a few times that of a hydrogen atom. QUEST-DMC uses superfluid helium-3, a light and stable isotope of helium with a nucleus of two protons and one neutron, cooled into a macroscopic quantum state to achieve record-breaking sensitivity in spotting ultraweak interactions.

QUEST-DMC wouldn't be capable of spotting extremely light axions, however, which are theorized to have masses billions of times lighter than a hydrogen atom. This also means such axions wouldn't be detectable by their interaction with ordinary matter particles.

Yet what they lack in mass, axions are posited to make up in number, with these hypothetical particles suggested to be extremely abundant. That means it's better to search for these dark matter suspects using a different signature: the tiny electrical signal resulting from axions decaying in a magnetic field.

If such a signal exists, detecting it would require stretching detectors to the maximum level of sensitivity allowed by the rules of quantum physics. The team hopes that their Quantum Sensors for the Hidden Sector (QSHS) quantum amplifier would be capable of doing just that.

If you are in the U.K., the public can view both the QSHS and QUEST-DMC experiments at Lancaster University's Summer Science Exhibition. Visitors will also be able to see how scientists infer the presence of dark matter in galaxies by using a gyroscope-in-a-box that moves strangely due to unseen angular momentum.

Additionally, the exhibition features a light-up dilution refrigerator to demonstrate the ultralow temperatures required by quantum technology, while its model dark matter particle collision detector shows how our universe would behave if dark matter interacted with matter and light just as everyday matter does.

The team's papers detailing the QSHS and QUEST-DMC experiments were published the journal The European Physical Journal C and on the paper repository site arXiv.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.