NASA Will Aim a DART at Target Asteroid in Upcoming Deflection Test

Nudging this asteroid will give valuable clues for surviving a prospective hit.

Telescopes and spacecraft are already watching the skies for potentially hazardous asteroids, but what could be done to actually deflect a dangerous object heading toward Earth?

On May 1, the audience at the 6th International Academy of Astronautics Planetary Defense Conference heard more than a dozen presentations related to an upcoming test to nudge an asteroid, and the potential follow-up mission that would view the results up close.

The upcoming mission, called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), will send a spacecraft to crash into an object typical of the size of those asteroids that could pose a threat to Earth. According to NASA, almost one-sixth of the known near-Earth asteroids (NEA) are multiple-body or binary systems, and DART will travel to one such system to perform its mission.

Related: Images: Potentially Dangerous Asteroids

The overall goal of the mission — which will conduct its crash test in about two years — is to gauge what future tools can successfully deflect the orbit of a potentially hazardous asteroid. The mission is led by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) and is managed by the Planetary Missions Program Office at Marshall Space Flight Center for NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

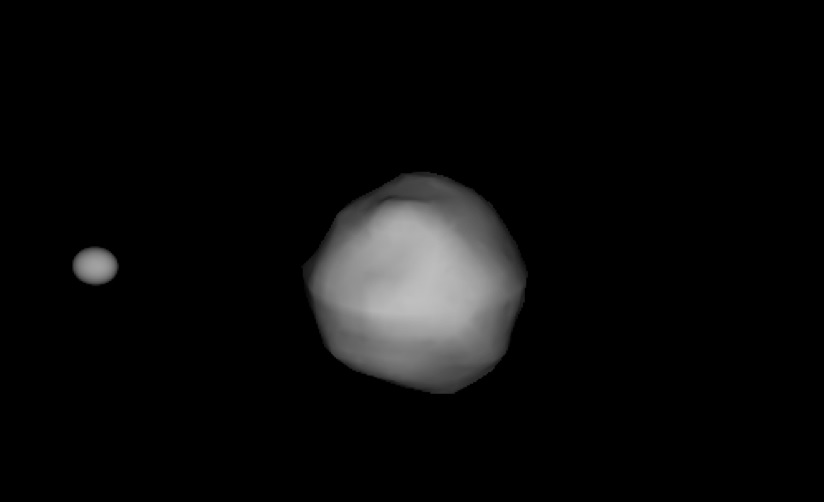

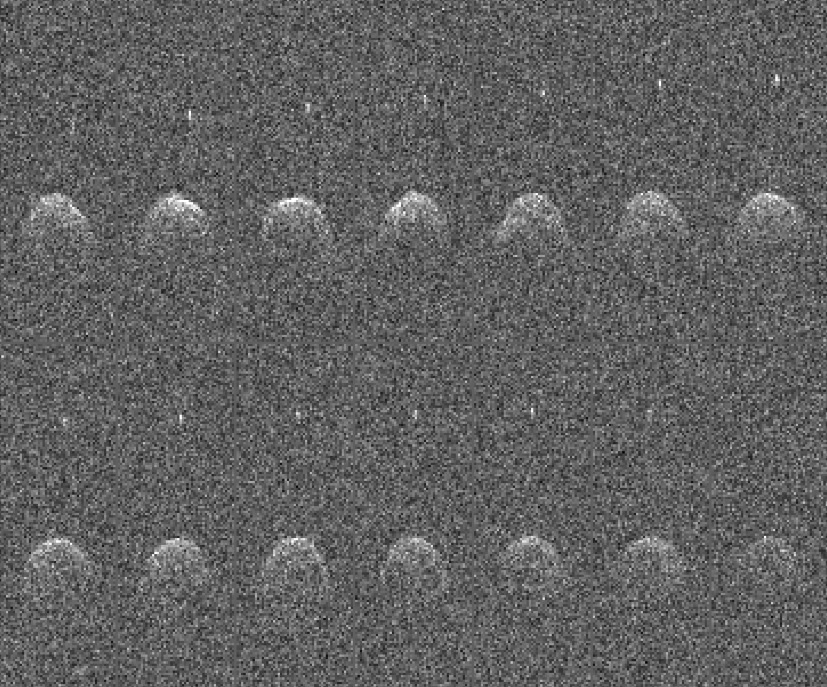

DART will travel to the binary asteroid system 65803 Didymos and will slam into the smaller of the two objects, also known as "Didymoon'' or Didymos B. The two rocks may receive another earthly visitor after DART, too. The European Space Agency is proposing a mission called Hera, which would explore Didymos and, alongside the first two European cubesats to travel into deep space, learn about the aftermath of the DART impact.

Didymos is about 2,540 feet (775 meters) wide, and Didymoon measures 540 feet (165 m) across.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission's launch window is now slated to open in July 2021, according to DART Project Manager Cheryl Reed. She also said on May 1 that current estimates suggest the spacecraft will carry a mass of 1,224 lbs. (555 kilograms) and will achieve a closing speed of 14,900 mph (24,000 km/h) before smashing into Didymoon in 2022.

The spacecraft will use the "kinetic impactor" technique to strike Didymoon and change the asteroid's motion. (The probe will not employ any explosives.)

An element to this collision that several researchers touched on at the conference was how much material ejected from the asteroid after the spacecraft hit would help boost deflection — the momentum enhancement factor, which is known as beta. Research teams are working on 2D and 3D models to better understand how Didymoon's composition, surface material or DART's angle of impact, for example, would affect deflection.

The Hera mission will receive a final full funding decision in November 2019. If it does get the green light, Hera and its two cubesats, APEX and Juventas, will make a series of measurements, observing the shape of DART's impact crater, Didymoon's mass, the asteroid's density and porosity, and more.

- Even If We Can Stop a Dangerous Asteroid, Being Human May Mean We Don't Succeed

- InSight Mars Lander Snaps Dusty Selfie on Red Planet (Photo)

- NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office: How They Detect Asteroids Early

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.