NASA's DART mission will move an asteroid and change our relationship with the solar system

The dinosaurs didn't have a space agency; maybe if they did they'd still be here, would-be planetary defenders sometimes quip about their quest to avoid an asteroid impact.

Planetary defense aims to identify any asteroids on track to cause serious damage to Earth and, should such a threat arise, act to deflect the rock. Such an impact is the only natural disaster that we can prevent, planetary defense experts often say.

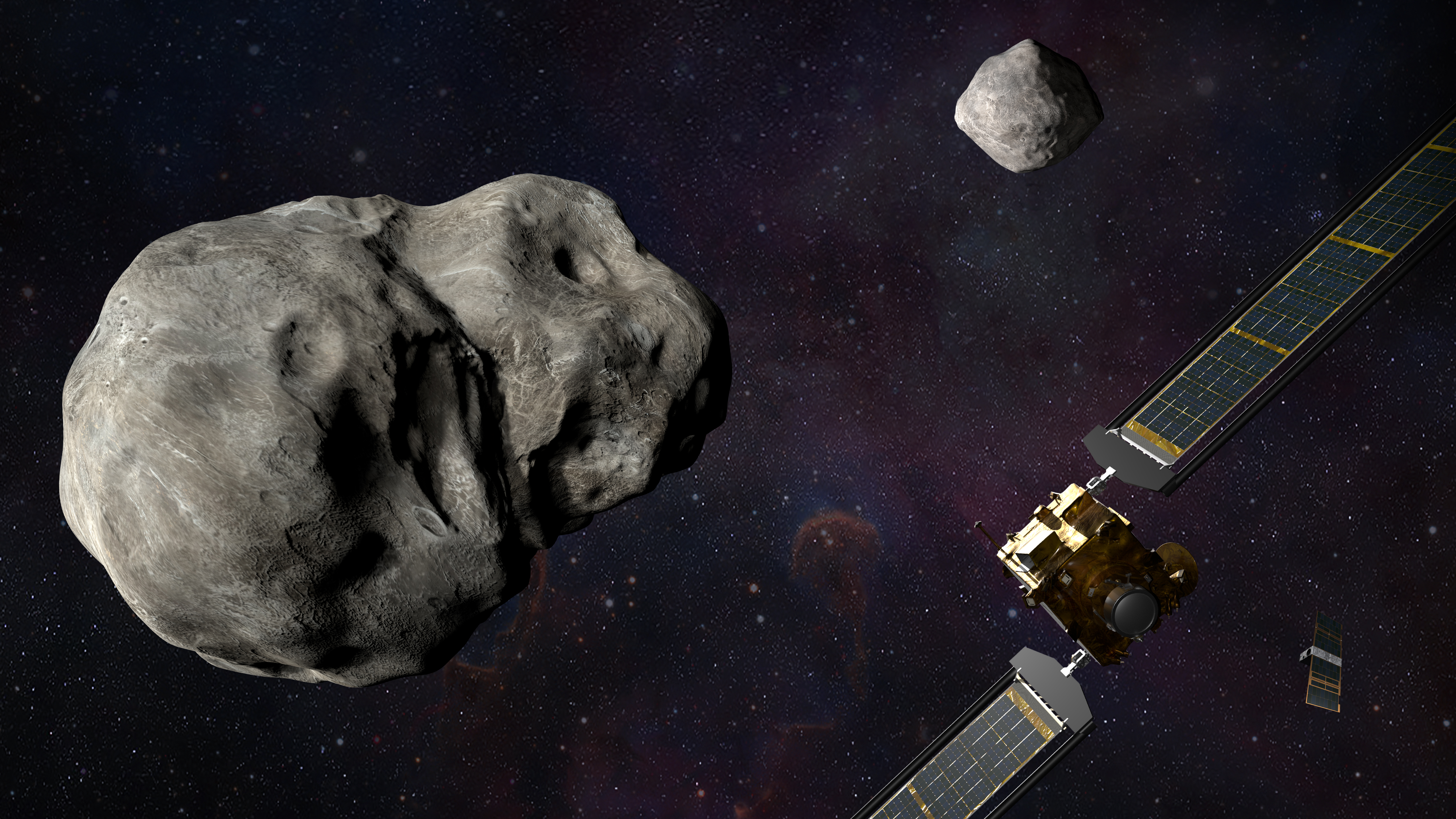

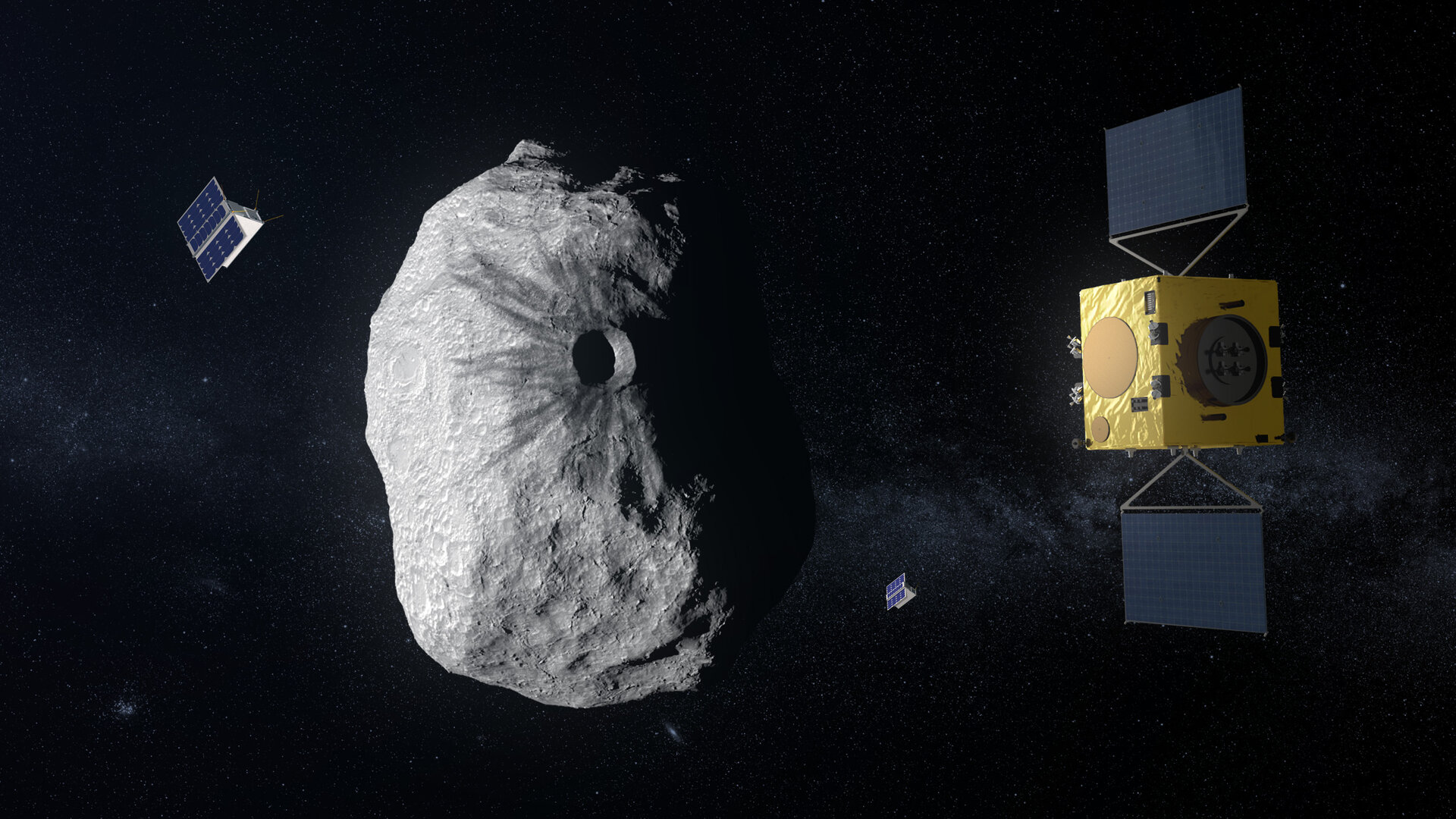

But planning an asteroid deflection would be difficult today, given several outstanding questions about just how effective a maneuver would turn out to be in the real world. So next year, planetary defense will take a big step, conducting its first experiment to determine how such a deflection might play out in reality thanks to NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, which launches later this month.

Related: If an asteroid really threatened the Earth, what would a planetary defense mission look like?

In late September or early October of 2022, the 1,210-pound (550 kilograms) DART spacecraft will slam itself into an asteroid called Dimorphos. Scientists will be watching eagerly, measuring how much the impact speeds up the space rock's orbit around its larger companion, Didymos — the first real data about what it might really require to steer a threatening asteroid out of Earth's path.

It's just one rock, just a small change. Just to reduce the odds that we humans go the way of the dinosaurs. But DART's impact will also mark a new relationship between humans and the solar system we live in, a milestone perhaps worth contemplating.

A matter of scale

Over the decades, humanity has left footprints on the moon, rover tracks on Mars, a puff of metals in the atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn, silent robots scattered from the sun to beyond the edge of its influence. But until now, orbital mechanics have been free of human fingerprints, orchestrated only by gravity and chance and the bones of the solar system. It was never quiet, of course, but it was chaotic in precisely the same way as it ever had been.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

DART's impact will be the first human fingerprint on this eternal dance of the solar system — a nearly imperceptibly tiny one but a fingerprint nonetheless, the first time a coalition of humans have come together to purposely tap any one piece of the maelstrom around us.

"Humans are like — we can do anything in the solar system, we can even move things out of the way," Ellie Armstrong, a geographer of outer space at the University of Delaware, told Space.com.

"Intervening in small-body dynamics is just a huge deal," Valerie Olson, an anthropologist at the University of California Irvine who has studied the planetary defense community, told Space.com, Early advocates of planetary defense recognized that such a mission would at its core re-engineer the solar system, she noted.

To be clear, the experts who suggest looking at the bigger picture of the DART mission aren't necessarily saying that planetary defense should be abandoned — just that it's an endeavor worth thinking about from multiple perspectives and in multiple contexts, rather than letting one narrative of what it means to save the planet dominate the conversation.

"Is it important that we figure out whether or not we can deflect an asteroid in the case of an emergency situation? Yes," Natalie Treviño, an independent critical theorist who focuses on space, told Space.com. "But we're kind of looking at our own planet being literally and metaphorically on fire."

Treviño compared asteroid deflection to damming a river on Earth as an action that might benefit humans but that has broader consequences across the environment. "What is our responsibility to our solar system?" Treviño said. "Do we have, as humans, the right to be making these massive changes to the solar system? But also, what precedent does it set?"

Considering rearranging the solar system requires not only looking ahead, however, but also looking back to evaluate what human histories may influence such an action — and whether we want to create a new, different way.

"Even the idea of being able to move and exploit and destroy or change natural capital like rocks and asteroids is very fundamentally pinned to an imperial worldview that sees humans as being allowed to do whatever they want," Armstrong said.

Who is in the room?

If we humans like to meddle, where is the line between endearing curiosity and something more serious? That line may depend on not just the scale of effect on orbital dynamics, but also on who is making the decisions about a planetary defense project.

All three experts noted that, although the worst-case impact scenario could destroy on a regional scale and have global consequences, only a handful of nations have the spacefaring capability to contemplate embarking on a planetary defense mission. A challenge the planetary defense community often considers is how to ensure that non-spacefaring nations have a say in how Earth responds to an asteroid threat.

"It's very particular people in particular agencies making decisions about how to intervene in the most natural and least social of spaces, which is outer space." Olson said. "What responsibility do those groups have to inclusively negotiate the defense and protection of all people, of the planet in general?"

The DART mission specifically does include some international collaboration, as it stems primarily from yearslong discussion between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). The pair of agencies initially explored a joint mission; the DART mission as it will finally launch includes a cubesat contributed by Italy and will be followed by an ESA mission called Hera that will evaluate the wreckage up close later this decade.

But the mission has perhaps flown under the radar, even among the nations whose agencies are taking part. "The majority of the public, whether that's an American public or the world in general, aren't particularly aware of this mission," Treviño said. "No one went out and said, 'Hey public, hey world, what do you think about this idea?'"

Treviño and her colleagues worry that this lack of public input into a mission of this consequence might replicate past and continuing situations where some more powerful people have made decisions for others on Earth in displays of colonialism, imperialism and militarism. "Something that strikes me as really interesting about this is the kind of national savior narrative, this very imperialist narrative of being able to save the world," Armstrong said.

And of course, planetary defense technology — like all other technologies ever developed — could be abused. "The very same technologies that can be used to move something can be used to weaponize something," Olson said.

Turn planetary defense on its head, for example. Treviño painted a nightmare scenario of a group being able to hold an asteroid hostage, looming over other communities. "I hate to be the naysayer, the killjoy, but to say, 'OK, we can just move something in the solar system just to see if we can do it' — where does that end up going, and what are the ramifications?" Treviño said.

DART is a carefully designed mission, and its target was chosen in part because scientists don't see any way that the mission could knock the rocks onto a collision course with Earth. But for a real planetary defense mission, if something does go wrong, the results may be very grim indeed, turning a natural disaster into a social one instead of preventing anything, Olson said.

"This is a step-by-step process, and the step that calls itself a practice step in which nothing can go wrong is only one step toward the next step," Olson said.

One threat among many

Perhaps the loudest concern boils down to how governments, agencies, and the public prioritize different disasters. The DART mission's framing and outreach suggest a reckoning of today's threats that is not universal, no matter how the future turns out.

"A lot of the rhetoric around this project is about how this is one of the biggest problems that might face Earth," Armstrong said, contrasting the decisiveness of a planetary defense strategy with floundering attempts in the United States and abroad to address, say, the climate crisis.

At $330 million, the DART mission is hardly a budget-buster. The annual budget of NASA's Earth Science Division sits around $2 billion. But that department's language talks about monitoring a changing planet, making a difference in people's lives and giving policymakers the knowledge to make informed decisions. It's a far cry from deflecting an asteroid to defend the planet, even as biologists say that a sixth mass extinction is underway, spurred primarily by human activity.

"I'm interested in what this says about what kind of problems America wants to be seen to be solving or NASA wants to be seen to be solving," Armstrong said. "You are literally moving a whole asteroid, and you are not making similar innovations in technology for very real problems."

The fall of the dinosaurs, cinematic as it was, is only one of five mass extinctions that paleontologists have registered in the fossil record. Although asteroid impacts are potential triggers for some of these other mass extinctions as well, space rocks certainly aren't responsible for all of these revolutionary periods of upheaval in what it means to be alive on Earth.

Even when asteroids are involved, an impact is only the trigger. The global killer in an asteroid impact isn't necessarily the rock itself: The rapid extreme climate swings that follow can be much more brutal. And climate upheaval can happen with no asteroid in the picture — as we, of all beings, know firsthand.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.