Death in space: Here's what would happen to our bodies

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Tim Thompson, Dean of Health & Life Sciences + Professor of Applied Biological Anthropology, Teesside University, the U.K.

As space travel for recreational purposes is becoming a very real possibility, there could come a time when we are travelling to other planets for holidays, or perhaps even to live. Commercial space company Blue Origin has already started sending paying customers on sub-orbital flights. And Elon Musk hopes to start a base on Mars with his firm SpaceX.

This means we need to start thinking about what it will be like to live in space – but also what will happen if someone dies there.

After death here on Earth the human body progresses through a number of stages of decomposition. These were described as early as 1247 in Song Ci’s The Washing Away of Wrongs, essentially the first forensic science handbook.

First the blood stops flowing and begins to pool as a result of gravity, a process known as livor mortis. Then the body cools to algor mortis, and the muscles stiffen due to uncontrolled build-up of calcium in the muscle fibres. This is the state of rigor mortis. Next enzymes, proteins which speed up chemical reactions, break down cell walls releasing their contents.

At the same time, the bacteria in our gut escape and spread throughout the body. They devour the soft tissues - putrefaction - and the gases they release cause the body to swell. Rigor mortis is undone as the muscles are destroyed, strong smells are emitted and the soft tissues are broken down.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These decomposition processes are the intrinsic factors, but there are also external factors which influence the process of decomposition, including temperature, insect activity, burying or wrapping a body, and the presence of fire or water.

Mummification, the desiccation or drying out of the body, occurs in dry conditions which can be hot or cold.

In damp environments without oxygen, adipocere formation can occur, where the water can cause the breakdown of fats into a waxy material through the process of hydrolysis. This waxy coating can act as a barrier on top of the skin to protect and preserve it.

But in most cases, the soft tissues will ultimately disappear to reveal the skeleton. These hard tissues are much more resilient and can survive for thousands of years.

Halting decomposition

So, what about death in the final frontier?

Well, the different gravity seen on other planets will certainly impact the livor mortis stage, and the lack of gravity while floating in space would mean that blood would not pool.

Inside a spacesuit, rigor mortis would still occur since it is the result of the cessation of bodily functions. And bacteria from the gut would still devour the soft tissues. But these bacteria need oxygen to function properly and so limited supplies of air would significantly slow down the process.

Microbes from the soil also help decomposition, and so any planetary environment that inhibits microbial action, such as extreme dryness, improves the chances of soft tissue preserving.

Decomposition in conditions so different from the Earth’s environment means that external factors would be more complicated, such as with the skeleton. When we are alive, bone is a living material comprising both organic materials like blood vessels and collagen, and inorganic materials in a crystal structure.

Normally, the organic component will decompose, and so the skeletons we see in museums are mostly the inorganic remnants. But in very acidic soils, which we may find on other planets, the reverse can happen and the inorganic component can disappear leaving only the soft tissues.

On Earth the decomposition of human remains forms part of a balanced ecosystem where nutrients are recycled by living organisms, such as insects, microbes and even plants. Environments on different planets will not have evolved to make use of our bodies in the same efficient way. Insects and scavenging animals are not present on other planets in our system.

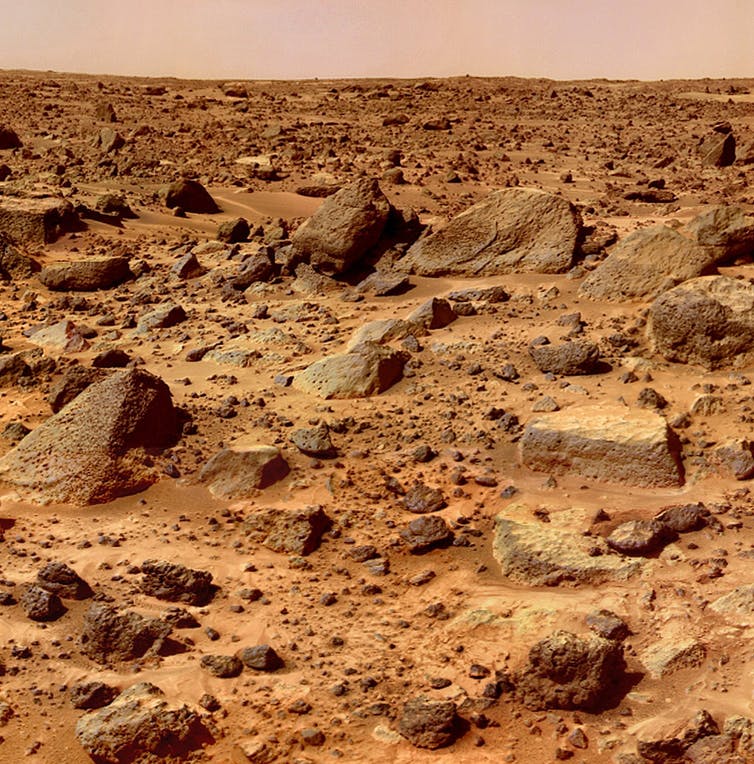

But the dry desert-like conditions of Mars might mean that the soft tissues dry out, and perhaps the windblown sediment would erode and damage the skeleton in a way that we see here on Earth.

Temperature is also a key factor in decomposition. On the moon, for example, temperatures can range from 250 to -270 degrees Fahrenheit (120 to -170 degrees Celsius). Bodies could therefore show signs of heat-induced change or freezing damage.

But I think it is likely that remains would still appear human as the full process of decomposition that we see here on Earth would not occur. Our bodies would be the "aliens" in space. Perhaps we would need to find a new form of funerary practice, which does not involve the high energy requirements of cremation or the digging of graves in a harsh inhospitable environment.

Read more: William Shatner oldest astronaut at 90 – here's how space tourism could affect older people

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tim Thompson is Dean of the School of Health & Life Sciences at Teesside University and Professor of Applied Biological Anthropology. Previously he was Associate Dean (Learning & Teaching) for three years in the School of Science, Engineering & Design and Associate Dean (Academic) in the School of Health & Life Sciences. In 2014, Tim was awarded a prestigious National Teaching Fellowship by the Higher Education Academy for excellence in teaching and support for learning in higher education and in 2021 his contribution was recognised through conferment as Principal Fellow.

Before coming to Teesside, Tim studied for his PhD at the University of Sheffield (Faculty of Medicine) and was a Lecturer in Forensic Anthropology at the University of Dundee.