Largest dark energy map could reveal the fate of the universe

This is one big map.

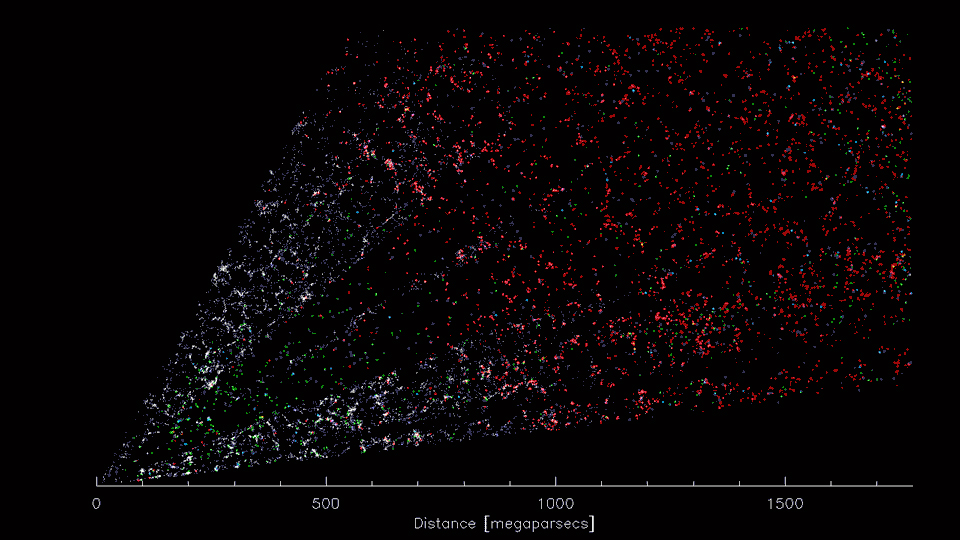

A modified telescope in Arizona has produced an interim map, which is already the largest three-dimensional map of the universe ever — and the instrument is only about a tenth of the way through its five-year mission.

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), a collaboration between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California and scientists around the world, was installed between 2015 and 2019 on the Mayall telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in the Sonoran Desert, about 50 miles (88 kilometers) west of Tucson, and has been conducting a survey for less than a year.

Its purpose is to create an even larger 3D map of the universe, to yield a better understanding of the physics of dark energy, the mysterious force that is accelerating the expansion of the universe.

Related: Did a dark energy discovery just prove Einstein wrong? Not quite.

"There is a lot of beauty to it," said Julien Guy, a physicist at Berkeley Lab who is working on the project. "In the distribution of the galaxies in the 3D map, there are huge clusters, filaments and voids.

"They're the biggest structures of the universe," he added. "But within them, you find an imprint of the very early universe and the history of its expansion since then." The researchers hope that understanding the effects of dark energy could help them determine the ultimate fate of the universe.

The DESI team used a giant two-dimensional map of the universe released in January 2021 to prepare the instrument for the three-dimensional survey, which started a few weeks later.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new 3D map pinpoints the locations of over 7.5 million galaxies, greatly exceeding the previous record of roughly 930,000 galaxies set by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in 2008.

Galaxy survey

DESI collects spectroscopic images of millions of galaxies spread out across about a third of the sky, according to a statement from Berkeley Lab.

By examining the color spectrum of the light from each galaxy, scientists can determine how much the light has been "redshifted" — that is, stretched toward the red end of the spectrum by a Doppler effect caused by the expansion of the universe. In general, the greater a galaxy's redshift, the faster it is moving away and the farther it is from observers on Earth.

Our universe has been expanding since it began with the Big Bang about 13.8 billion years ago, and it is now much larger — at least 92 billion light-years across — than the farthest distances we can see.

Related: From Big Bang to present: Snapshots of our universe through time

Scientists with the DESI project hope their 3D map of the cosmos will reveal the "depth" of the sky and help them chart clusters and superclusters of galaxies, according to the statement. Because those structures carry echoes of their initial formation as physical ripples in the material of the infant cosmos, the researchers hope to use the data to determine the expansion history of the universe — and its ultimate fate.

"Our science goal is to measure the imprint of waves in the primordial plasma," Guy said. "It's astounding that we can actually detect the effect of these waves billions of years later, and so soon in our survey."

Dark energy

Scientists used to think that the universe was expanding at a constant rate, or that the combined matter and energy in the universe might eventually cause that expansion to slow down. But observations of powerful stellar explosions called supernovas beginning late in the past century showed that the expansion is actually accelerating, so scientists coined the phrase "dark energy" to account for this unexpected phenomenon.

Calculations now suggest that dark energy makes up around 70% of the total energy in the observable universe. The effects of dark energy are now recognized as the "cosmological constant" that Albert Einstein included in his theory of general relativity; understanding dark energy has become a crucial scientific goal in recent decades, according to Smithsonian magazine.

It seems that more dark energy is created as the universe expands, which accelerates the expansion of the universe, according to the statement.

Ultimately, the effects of dark energy will determine the destiny of the universe — whether it expands forever, rips itself apart or collapses again in a type of reverse Big Bang.

DESI is now cataloging the redshifts of about 2.5 million galaxies every month. The team expects to complete the 3D survey map in 2026, by which time the telescope will have observed an estimated 35 million galaxies.

DESI scientists are presenting some early astrophysical results from the instrument this week at a webinar hosted by the Berkeley Lab, called CosmoPalooza.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.