Hubble telescope spots doomed star that is the 'Rosetta stone' of supernovas

The observatory cataloged a star's 'cataclysmic demise'

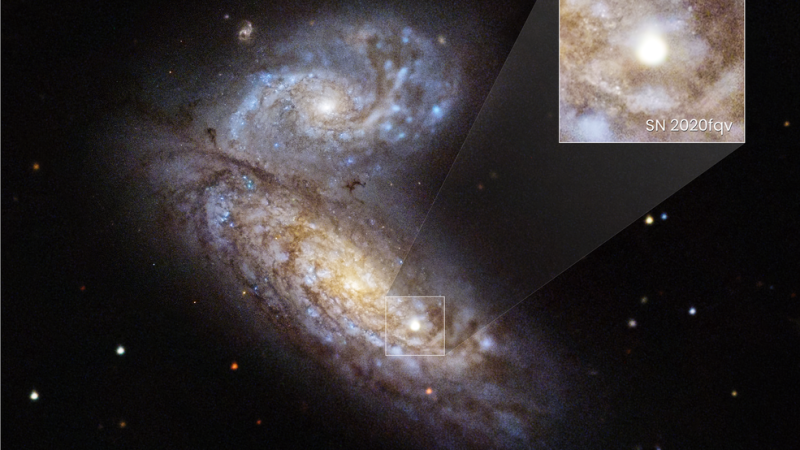

A new supernova captured by the Hubble Space Telescope may act as a decoder for other star explosions.

Given that the telescope caught the star so early in its "cataclysmic demise," as NASA called it, astronomers say the research may eventually help them formulate an early warning system for other stars that might be about to explode.

Scientists are dubbing the event, known as SN 2020fqv, as the "Rosetta Stone of supernovas." That's a reference to the Rosetta Stone, which has the same text written in three different scripts, allowing historians to read Egyptian hieroglyphs. (The stone was inscribed in ancient Greek, which was well-known to scholars, as well as two forms of Egyptian script, which were then poorly understood.)

The actual stone, dating from about 2,200 years ago, was found by accident in 1799 by soldiers in Napoleon's army campaigning in Egypt; you can see it today in the British Museum in London. Investigators for the Hubble discovery admitted the term "Rosetta Stone" is used often as a metaphor for deciphering information, but noted the term is an apt description for the importance of this new cosmic work.

Related: The best Hubble Space Telescope images of all time!

"This is the first time we've been able to verify the mass with these three different methods for one supernova, and all of them are consistent," lead author Samaporn Tinyanont, a graduate student in astronomy at California Institute of Technology, said in a NASA statement.

"Now we can push forward using these different methods and combining them, because there are a lot of other supernovas where we have masses from one method but not another."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SN 2020fqv was found amid the Butterfly galaxies, a pair of spiral galaxies located roughly 60 million light-years away from Earth in the constellation Virgo. The supernova was first discovered in April 2020 by the Zwicky Transient Facility at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego, California.

Coincidentally, the supernova was also in the view of the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), whose primary mission is to search for relatively nearby planets outside of our solar system. Soon, Hubble and several ground-based telescopes joined the multinational observatory star party.

Hubble's sharp eyes allowed the observatory to look at the material close by the star, known as circumstellar material, only a few hours after the explosion occurred. Because the material clung onto the star until the last year of its life, astronomers say studying this stuff allows further research into what the star was doing before it died.

"We rarely get to examine this very close-in circumstellar material since it is only visible for a very short time, and we usually don't start observing a supernova until at least a few days after the explosion," Tinyanont said. "For this supernova, we were able to make ultra-rapid observations with Hubble, giving unprecedented coverage of the region right next to the star that exploded."

Helpfully, Hubble also has an archive of observations of this star dating to the 1990s. Astronomers probed the image series and added TESS observations of the system every 30 minutes in the days before the explosion, as well as during the explosion itself and for a few more weeks (before, we assume, the standard schedule of TESS shifted the telescope to gaze at another spot in the sky.)

Scientists then calculated the mass of the exploding star using three different methods: comparing observations with theoretical models, using information from a 1997 archival image of Hubble (this was to rule out higher-mass stars in the model), and measuring the amount of oxygen in the supernova, which is a proxy for mass. All three methods produced consistent results, with an estimate of 14 to 15 times the mass of our own sun.

One of the more famous unstable stars is Betelgeuse, a red supergiant that is late in its life and put up some antics in the last year or so. Co-author Ryan Foley, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said he doesn't believe Betelgeuse itself is about to explode, but added that SN 2020fqv will help in building our database of stars to watch.

"This could be a warning system," Foley said of the explosion behavior Hubble and other observatories noted. "So if you see a star start to shake around a bit, start acting up, then maybe we should pay more attention and really try to understand what's going on there before it explodes. As we find more and more of these supernovae with this sort of excellent data set, we'll be able to understand better what's happening in the last few years of a star's life."

A paper based on the research was published Thursday (Oct. 21) in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.