Dwarf planet Ceres once had a muddy ocean, study suggests

'Ceres, we think, is therefore the most accessible icy world in the universe.'

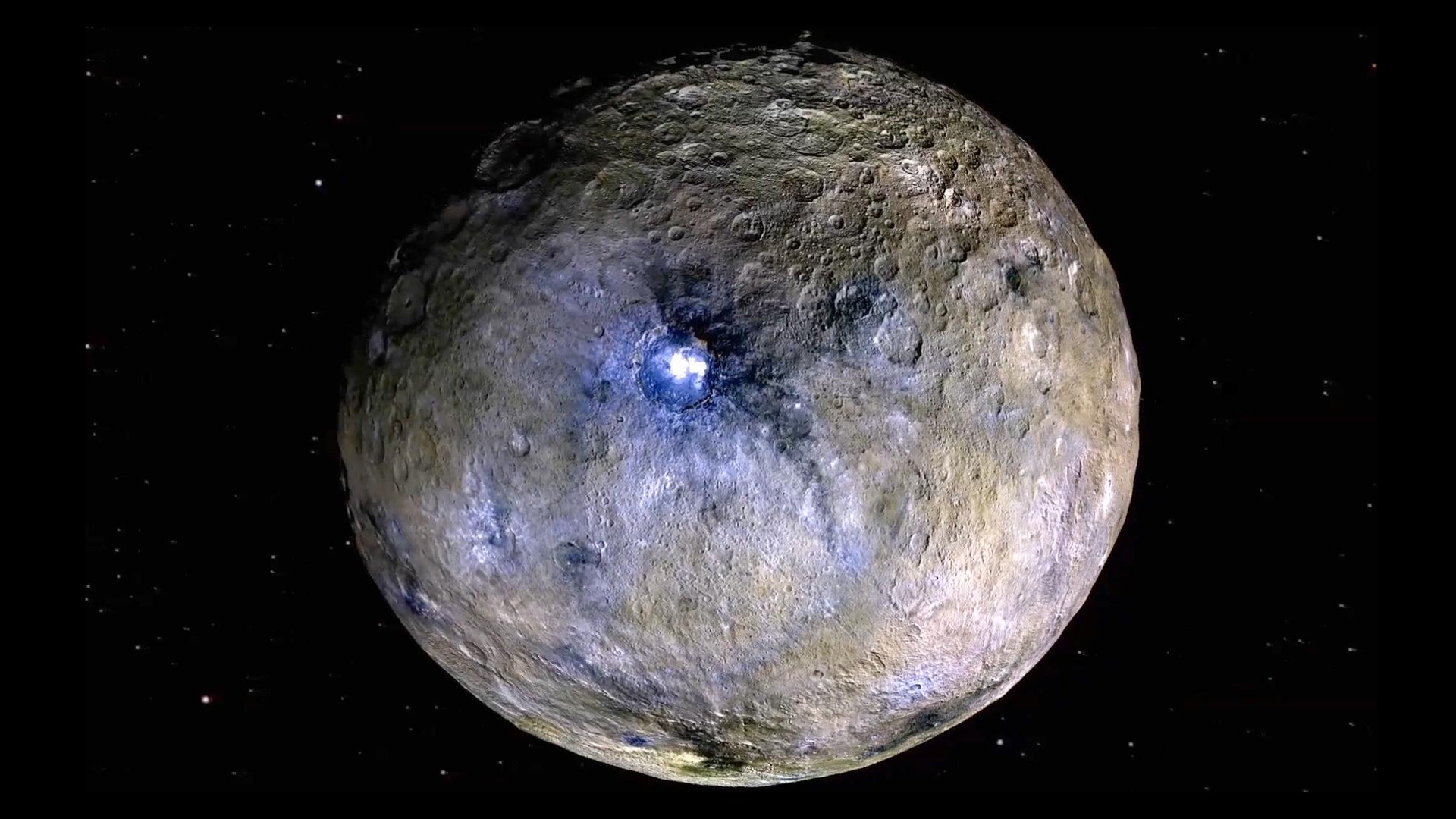

The outer crust of the dwarf planet Ceres, which at 588 miles (946 kilometers) across is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, is likely made from a dirty frozen ocean, according to new computer models.

Ceres has many of the hallmarks of being ice-rich. "Different surface features — pits, domes and landslides, etc — suggest the near-subsurface of Ceres contains a lot of ice," Ian Pamerleau, who is a Ph.D. student at Purdue University in Indiana, said in a statement. Spectroscopic data also points to there being ice beneath the dusty regolith on the surface, while measurements of the dwarf planet's gravity field also suggest a density similar to impure ice.

Yet planetary scientists were generally not convinced, particularly after NASA's Dawn spacecraft gave us our first good look at Ceres, which the probe orbited between 2015 and 2018.

On known icy ocean worlds such as Jupiter's moons Europa and Ganymede, or the Saturn satellite Enceladus, large craters are relatively few. That's because ice can flow, as in the case of glaciers on Earth, and crater walls made of ice will eventually soften and flow back into the surface, leading to the craters becoming shallow or non-existent.

Related: Dwarf planet Ceres could be a great place to hunt for alien life. Here's why

Yet Dawn found that there were plenty of stark craters with steep walls on Ceres' battered terrain.

"The conclusion after NASA's Dawn mission was that, due to the lack of relaxed, shallow craters, the crust could not be that icy," said Pamerleau.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To put this to the test, Pamerleau, his Ph.D. supervisor Mike Sori, and Jennifer Scully of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory ran computer simulations that modeled how Ceres' craters would behave across billions of years, with differing amounts of ice, dust and rock in the dwarf planet's crust. They found that a crust made of 90% ice, with dust and rock mixed in, would barely flow in Ceres' gravity field, allowing craters to persist for the lifetime of the dwarf planet.

"Our interpretation of all this is that Ceres used to be an ocean world like Europa, but with a dirty, muddy ocean," said Sori. "As that muddy ocean froze over time, it created an icy crust with a little bit of rocky material trapped in it."

Long ago, after Ceres had formed and was still warm, this icy crust could have been liquid, forming a shallow ocean beneath a thin layer of ice. Researchers would love to find out how long this ocean persisted for, because even after the thermal heat of Ceres' birth had leaked out, heat from radioactive isotopes could have kept the ocean liquid for longer. Unlike Europa or Enceladus, it would be easier to study Ceres' frozen ocean to find the answers to questions such as this.

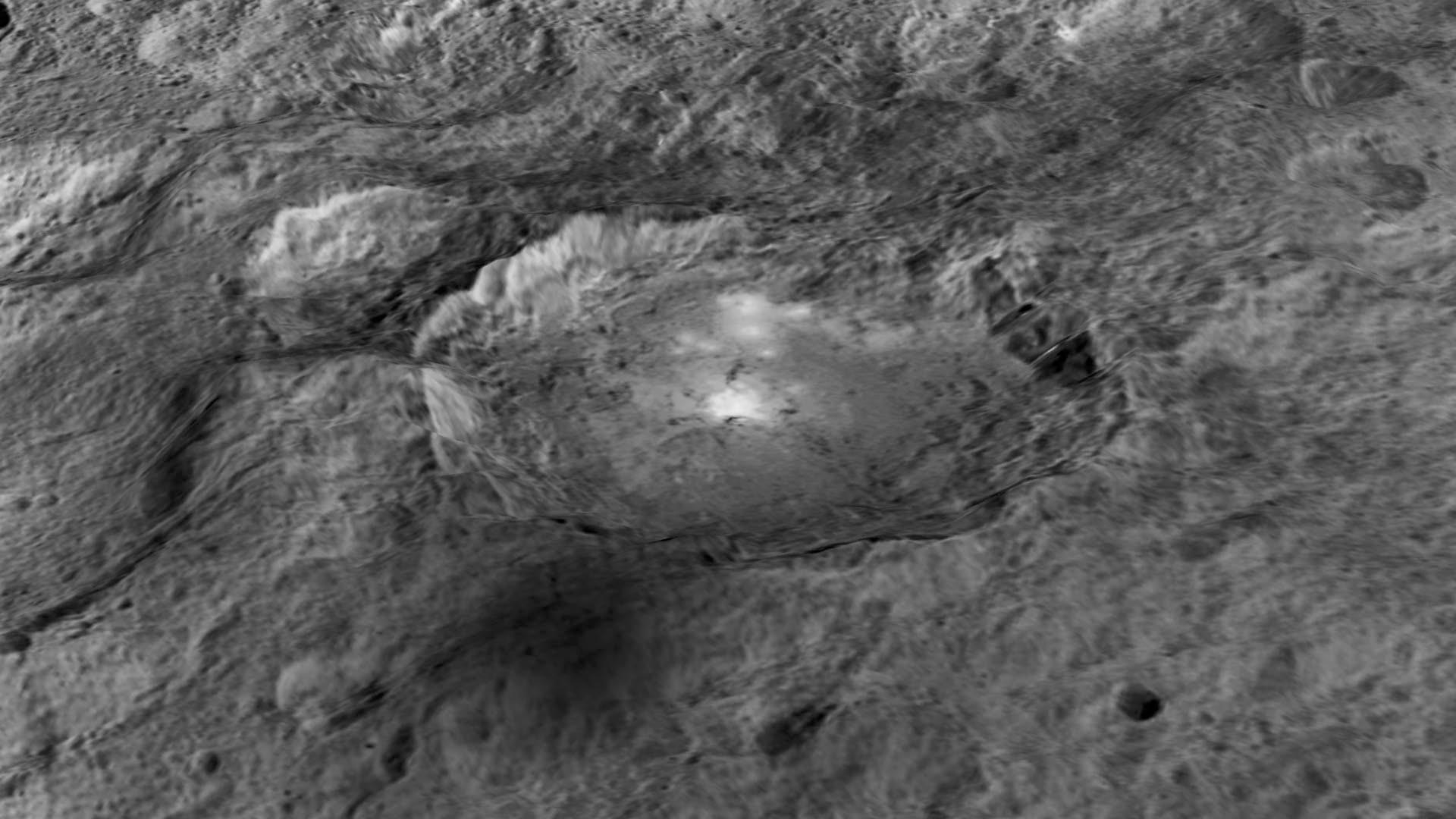

"To me, the exciting part of all this, if we're right, is that we have a frozen ocean world pretty close to Earth," says Sori. Its proximity to us and lack of other dangers, such as the radiation that missions to Europa face at Jupiter, could render Ceres relatively easy to retrieve samples from. There are areas where the underlying ocean seems to have burst through to the surface, leaving deposits, such as the bright areas seen by Dawn in Occator Crater among others.

"Ceres, we think, is therefore the most accessible icy world in the universe," Sori concluded.

The research was published on Sept. 18 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.