At the dark hearts of galaxies like the Milky Way lie supermassive black holes, with millions or even billions of times the sun's mass.

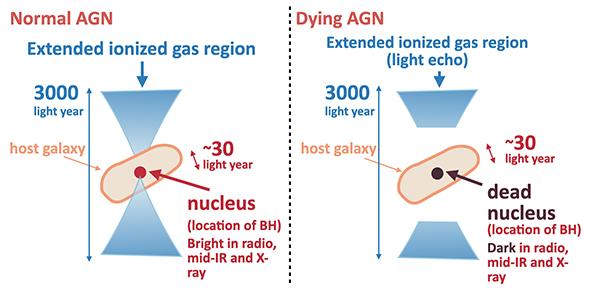

Some of those supermassive black holes are what scientists call active galactic nuclei (AGN), which spew out copious amounts of radiation like X-rays and radio waves. AGN are responsible for the twin jets of ionized gas you see shooting away in pictures of many galaxies.

As all things must pass, so too must every AGN one day shut off. But scientists have never quite understood how or when that happens. Now, researchers led by Kohei Ichikawa, an astronomer at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan, may have found a clue. Looking at the distant galaxy Arp 187, those researchers have seen what they think is an AGN in its very last days.

Related: Black holes of the universe (images)

Ichikawa and his colleagues observed Arp 187 with the radio telescopes at the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in northern Chile and the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico. They spotted twin jet lobes, a telltale sign of an AGN. But they couldn't detect radio waves, which also should have been coming from an active nucleus.

So, the researchers took a second look at Arp 187's core with NASA's NuSTAR ("Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array") X-ray satellite. AGN normally produce X-rays in abundance, but no such signal emerges in the NuSTAR data, the team reported in a study presented earlier this month at the 238th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which was held virtually.

The researchers therefore think that, sometime in the past several thousand years (as observed from Earth), Arp 187's AGN has gone dark.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This observation is possible because an AGN's jets are colossal. Arp 187's stretch out for 3,000 light-years, meaning that you can see their matter stream away for millennia after the AGN core "dies." Astronomers call this mourning period a "light echo." It's like watching smoke from a newly extinguished fire.

The researchers have called their discovery "serendipitous." Arp 187 could be a stepping stone to learning more about what happens at the end of an AGN's life, study team members said.

"We will search for more dying AGN using a similar method as this study," Ichikawa said in a statement. "We will also obtain the high spatial resolution follow-up observations to investigate the gas inflows and outflows, which might clarify how the shutdown of AGN activity has occurred."

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.