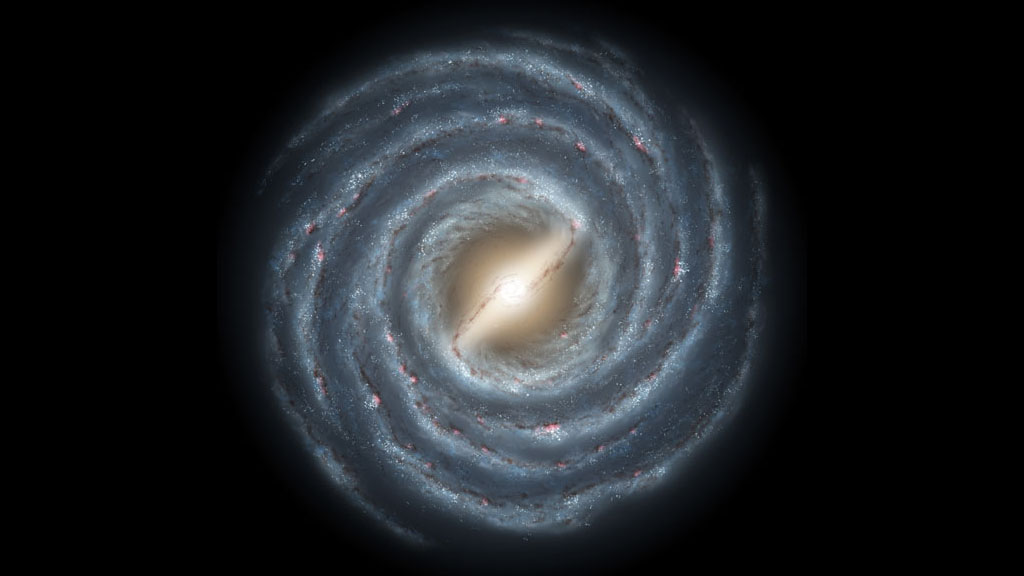

Our Milky Way Cannibalized a Neighbor to Become the Galaxy We See Today

Our Milky Way galaxy was born in violence and scientists are still piecing together a picture of the cosmic crime scene.

A crucial tool in that process is the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope, an instrument working to pinpoint the location of more than 1 billion stars. The information it gathers is letting astronomers understand how the Milky Way absorbed a second galaxy in the early days of the universe, a continuing process that's the subject of a paper published last week.

"Until now all the cosmological predictions and observations of distant spiral galaxies similar to the Milky Way indicate that this violent phase of merging between smaller structures was very frequent," Matteo Monelli, an astronomer at the Institute for Astrophysics in the Canaries and a co-author of the article, said in a statement. But scientists are still sorting out what happened to build the galaxy we know and love.

Related: Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)

That's where the ever-growing stash of Gaia observations came into play. The telescope's location observations let scientists wind the clock back on where all those stars have been traveling, and Gaia can also study the stars' composition.

Astronomers had already seen that one batch of Milky Way stars seemed bluer than another group, marking two different ancestral galaxies within today's structure. Gaia data made the new research possible, letting a team of astronomers determine that these two groups are about the same age — and that all of these stars are older than the ones in the Milky Way's disk. The new research also suggested that while one batch of older stars are predominantly hydrogen and helium, the other batch contains larger amounts of heavier elements.

That means the current story of the Milky Way goes something like this: 13 billion years ago, there was a small galaxy dubbed Gaia-Enceladus and the ancestor of our Milky Way, four times larger and richer in heavier elements. About 10 billion years ago, the two collided, and about 4 billion years later a spurt of star formation created the final segment of the Milky Way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new research is described in a paper published July 22 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

- Get Ready for Milky Way Season with These Galactic Night-Sky Photos

- Pretty Panoramic Milky Way Photo Resembles an Astronaut's-Eye View

- The Universe Reveals Its True Colors in This Stunning Milky Way Photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.