A vintage NASA moon rocket body is officially back in Earth orbit … for now

A relic of the early days of spaceflight has likely come back to pay a brief visit to its planet of origin, according to months of observations of a near-Earth object dubbed 2020 SO.

2020 SO entered what scientists call Earth's Hill sphere, where Earth's gravity governs how objects behave, on Nov. 8, according to a NASA statement. Scientists say that the object will make two leisurely loops around Earth before slipping away to resume its path around the sun in March.

But although scientists first spotted it in September during surveys conducted to identify asteroids, the object soon seemed to be something entirely different — a rocket's upper stage from a 1966 robotic NASA moon mission called Surveyor 2. And that would make it quite storied space junk indeed.

"If it is the Centaur upper stage," Alice Gorman, an archaeologist focused on spaceflight heritage, told Space.com, "it's this object in itself, it's this rocket stage, but it's also connected to all of these other things as well."

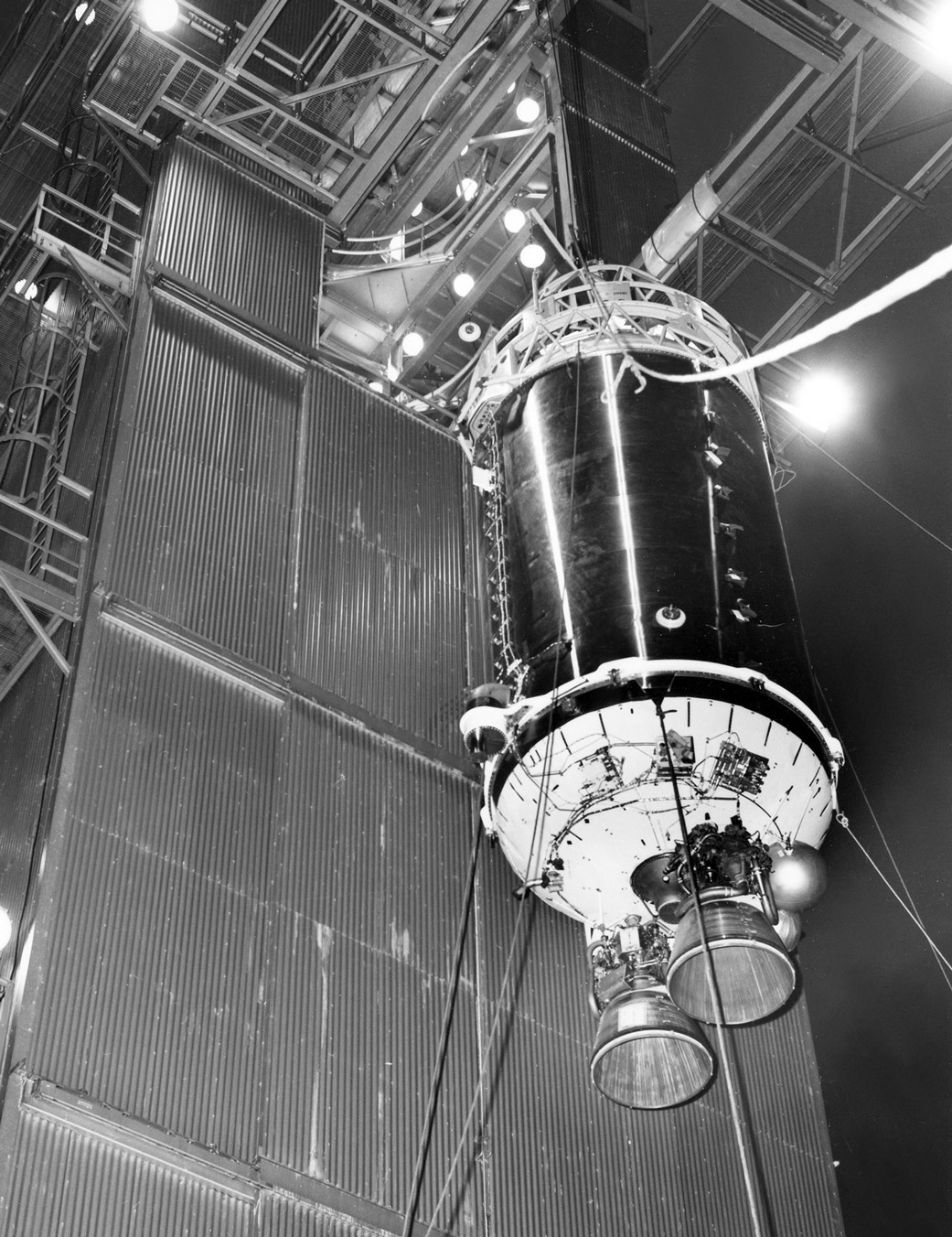

This particular hunk of metal left Earth on Sept. 20, 1966, perched atop an Atlas D first stage and carrying at its tip a spacecraft called Surveyor 2. Three days later, that spacecraft inadvertently crashed into the moon. The metal cylinder that had delivered it, meanwhile, breezed past our celestial neighbor and settled in to circle the sun more or less in tandem with our home planet.

And apparently, it's been doing that for 54 years. Throughout those years, the Centaur's successors have proliferated, blasting countless rockets off Earth and onto a host of Earth-orbital and planetary exploration missions.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A long career for a simple design

The Centaur rocket stage in one form or another has played a key role in space exploration for essentially the entire history of spaceflight. It was the result of a partnership between NASA (and its predecessor) and the commercial sector in the late 1950s and first launched in March 1962.

The stage was a vital development in rocketry because it was the first successful design to rely on dangerously temperamental but lightweight and efficient liquid hydrogen, according to a NASA-published history of the component. Centaur's success established that liquid hydrogen could be used safely, helping the U.S. catch up to the Soviet Union during the space race.

But despite that leading role, the Centaur upper stage is deceptively straightforward. "It's a really simple rocket," Gorman said. "It's just like a big fuel tank with a couple of rocket engines." And it's flexible: While over the years it has most commonly flown with the Atlas first stage, it can join with a range of rockets. In the 1980s, it was even adapted to launch inside NASA's space shuttle to guide satellites to their proper orbits, although it never ended up flying in that configuration.

Only one version of the Centaur stage continues to fly today, built into United Launch Alliance's Atlas V rockets, but it is also designed into the company's future Vulcan Centaur rocket, due to launch perhaps next year.

The Centaur's long history is a good reminder of the transitory, mix-and-match nature of every rocket, Gorman said. Launch vehicles spend much more time as their components, often spread across wide geographies, than they do as a single unit.

"In our minds, we have this vision of the rocket, which is the big tall spiky thing on the launchpad, but that rocket only exists for a short period of time," she said. "It's assembled in the week leading up to launch … it launches and separates and gets left in bits."

Surveying the moon

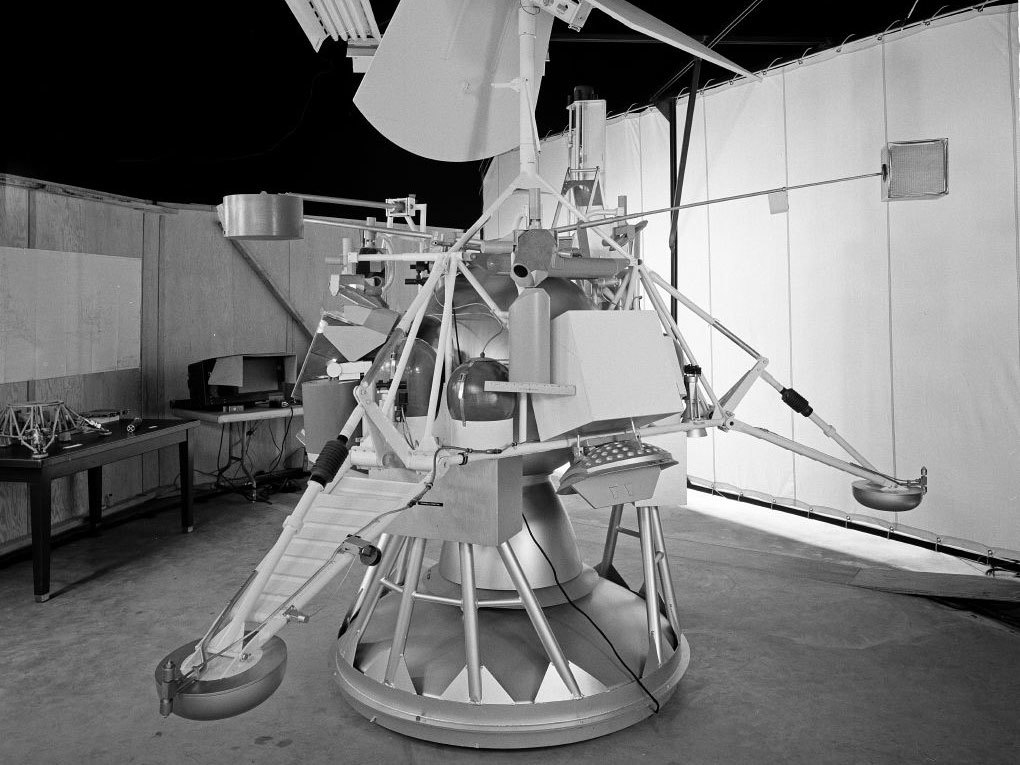

The particular Centaur bit now temporarily rattling around Earth was part of a vital suite of missions that led the way to the Apollo program by proving that it was safe to land on the moon, although its particular spacecraft failed.

Between 1966 and 1968, the U.S. launched seven missions dubbed Surveyor, each designed to land on the moon. Overall, the program was a success; Surveyor 2 itself was the lone exception when it crashed into the lunar surface.

Its predecessor probe, Surveyor 1, made the first American soft landing on the moon.

"Landing on the moon was truly exciting; it's kind of like landing on Mars nowadays," Paul Chodas, head of NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, who saw the object detected during asteroid surveys and realized it was likely the Surveyor 2 Centaur, told Space.com. "It's exciting especially because I do remember these missions. Surveyor 1 was a very exciting landing on the moon — as a kid, I was watching the moon through my telescope when it landed."

And the successful soft landing also provided vital evidence for the historic Apollo 11 human moon landing three years later, Gorman said.

"There were kind of two theories about lunar dust at that time: One was that it was incredibly deep, so if you sent a human mission, they would just sink into the dust, and the other was that the dust was not so deep," Gorman said. "So one of the things that the Surveyors did was prove that, at least in the locations where the seven missions landed, that the dust was not meters deep, so it would be safe for a much heavier craft to land on the surface. That's fairly significant in terms of the whole development of human spaceflight and lunar science."

But while Surveyor 2 may not have lived up to its siblings, its Centaur may well be on track to becoming the first sun-orbiting rocket body from the 1960s that scientists have rediscovered. Astronomers are planning on observing the object to attempt to confirm the connection, but for Chodas, the trajectory is compelling evidence on its own.

"The fact that it can be linked very strongly to the Surveyor 2 launch, which was 54 years ago, is truly amazing," Chodas said. "That's kind of the first time I've been able to make such a strong association with a rocket launch from the 1960s."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.