Earth's core wobbles every 8.5 years, new study suggests

Earth's core isn't exactly aligned with its mantle, which results in a cyclical wobble, new research finds.

Scientists in China recently made a discovery at the heart of our planet: Every 8.5 years, the Earth's inner core wobbles around its rotational axis. This shift is likely caused by a tiny misalignment between the inner core and the Earth's mantle—the layer below the Earth's crust, according to the researchers' new study.

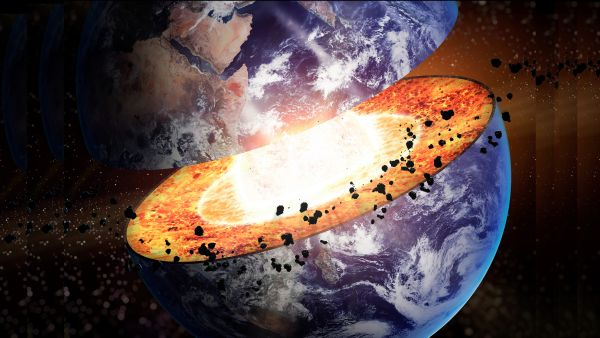

Starting around 1,800 miles (2896 km) beneath the surface, Earth's core is split into a swirling liquid outer boundary and a mostly solid inner layer. This region is partially responsible for a number of our planet's geophysical dynamics, from the length of each day to Earth's magnetic field, which helps protect humanity from harmful rays emitted by the sun.

This newfound tilt in the inner core could eventually lead to a change in the shape and motion of the liquid core, leading to a potential shift in Earth's magnetic field, according to the study published Dec. 8 in the journal Nature Communications.

Related: Human impact on Earth's tilt leaves researchers 'surprised and concerned'

To better understand the inner workings of this core, the geophysical researchers, led by Hao Ding of Wuhan University, analyzed in 2019 the movement of the Earth's rotational axis relative to its crust, which is known as polar rotation. They detected a slight deviation in polar motion occurring roughly every 8.5 years, indicating the potential presence of an "inner core wobble," similar to the wobble of a spinning top.

For their latest study, Ding and his co-authors further confirmed this cycle by measuring small shifts in day length around the world — which is controlled by the periodic movement of the Earth's rotational axis — and comparing them to the variations in polar motion they previously identified. Their data suggests that this wobble is likely caused by a tilt of 0.17 degrees between the Earth's inner core and mantle, which is contrary to the traditional Earth rotation theory that "assumes that the rotation axis of the Earth's inner core and the rotation axis of the mantle coincide," Ding told Live Science in an email.

This tilt may indicate that the northwestern hemisphere of the inner core might be slightly denser than the rest of this layer, and that there is also a difference in density between Earth's inner and outer core, according to the research.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study "helps discern the difference in composition between the metal in the solid inner and liquid outer core as well as estimates direction and speed of the wobble of the inner core," John Vidale, a professor of Earth science at University of Southern California, told Live Science in an email. "Nothing here to save humanity this week, but the work adds basic building blocks to understand our planet."

The research team ruled out atmospheric, oceanic and hydrological influences that may have caused the deviation in polar motion besides the inner core wobble. However, it is difficult to confirm these sources didn't play a part because "it takes many kinds of experts to assemble the kind of analysis done in this study," according to Vidale.

Moving forward, this discovery could help researchers understand the dynamics between Earth's inner core and processes that impact humanity, from earthquakes to changes in the magnetic field.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 9 a.m. EDT on Saturday, Dec. 30 to correct John Vidale's university affiliation.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Kiley Price is a Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and is pursuing a master's degree at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.