Earth-like planets in dead star 'cosmic graveyards' get stranger

The first world found orbiting a pulsar is rarer than previously believed, deepening the mystery of how planets survive around violent dead stars.

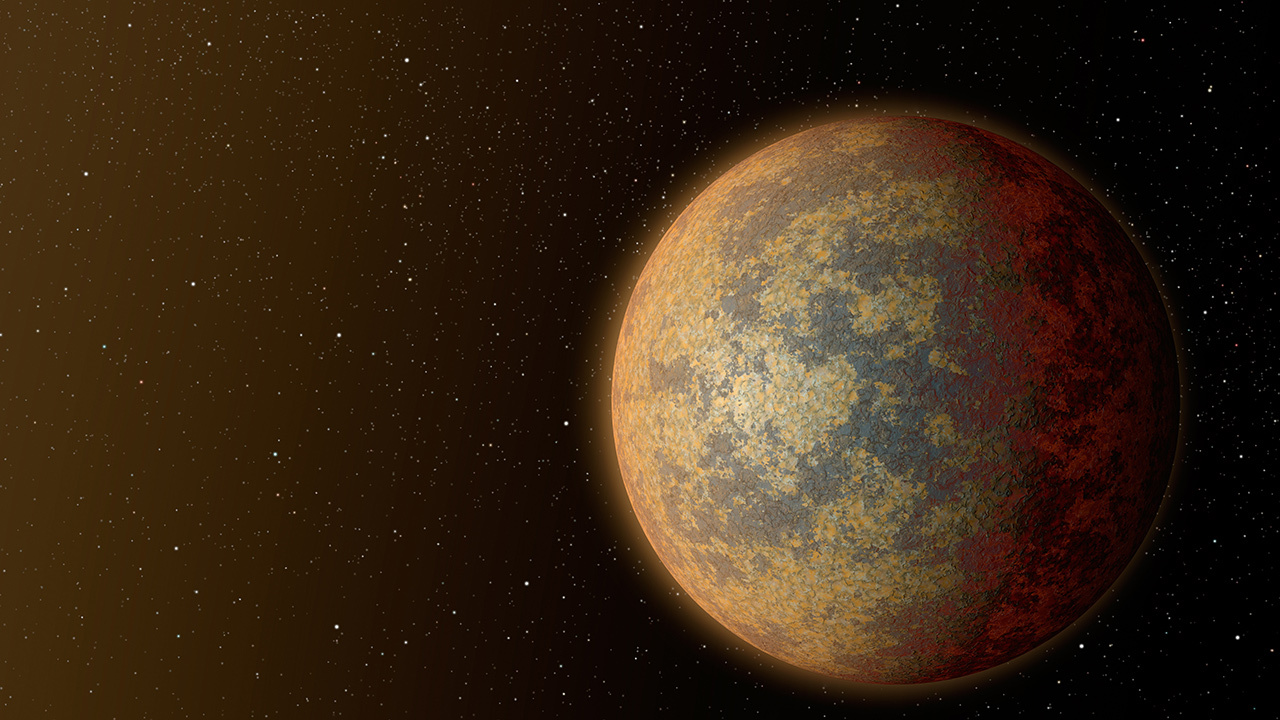

New findings show that Earth-size planets may be even less likely to survive the violent conditions at the end of some stars' lives than previously believed. This means that the first exoplanet discovered outside the solar system 30 years ago may be far weirder than we realized.

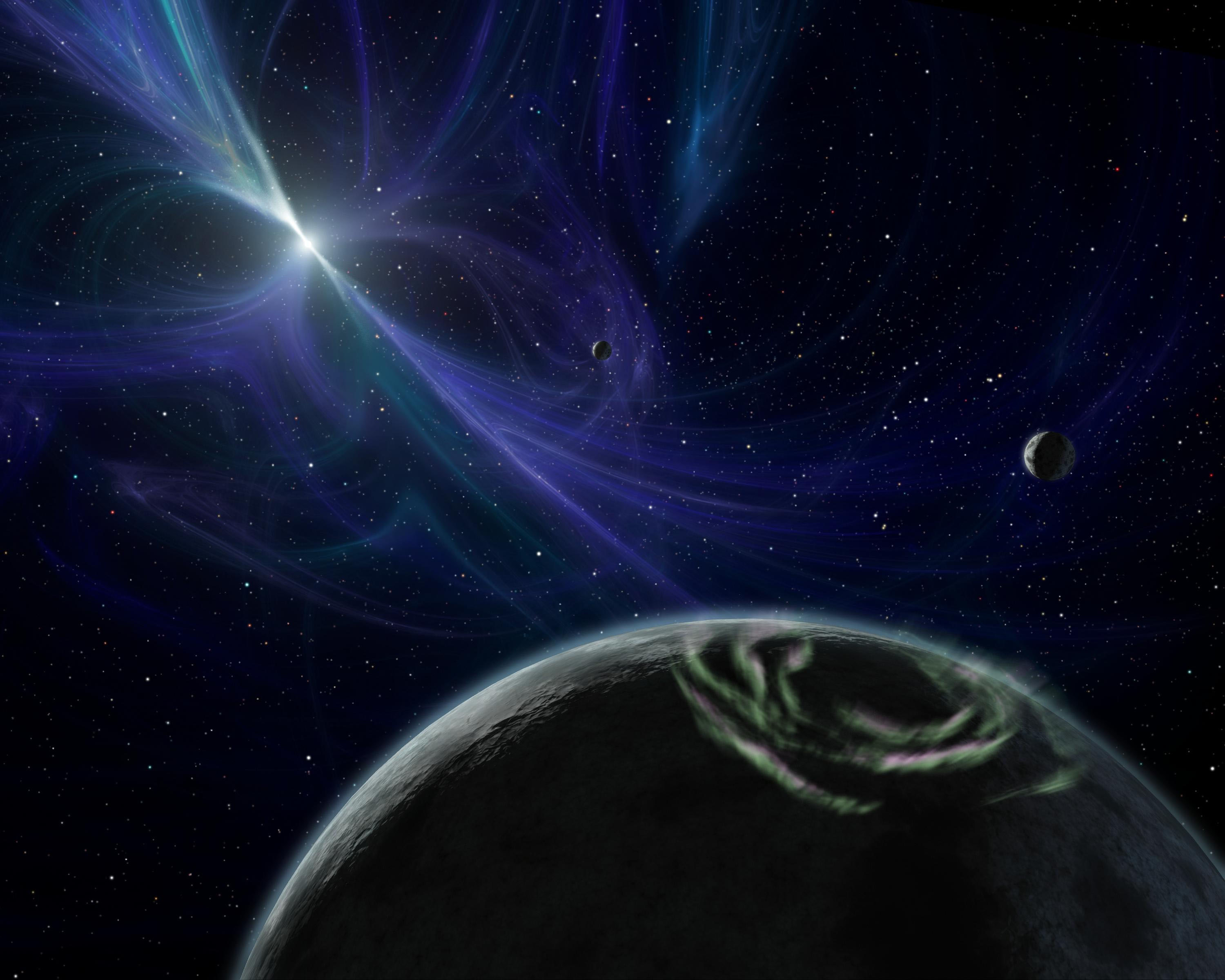

Discovered in 1992 by astronomers Alex Wolszczan and Dale Frail, the planet PSR B1257+12B has an Earth-like mass and orbits an exotic type of dead star called a pulsar. The discovery was followed by the revelation that the planet is accompanied by at least two other worlds. These other planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12 are also of similar sizes to the rocky worlds of the solar system.

However, the largest study of pulsars and their planets ever conducted has shown that these dead stars rarely possess Earth-like companions. That makes this system, which NASA describes as a "graveyard" following the supernova that created PSR B1257+1, a rarity.

Related: These 10 super extreme exoplanets are out of this world

And conditions in the system, located 2,300 light-years away from Earth, aren't getting any more hospitable. The pulsar at its heart spins every 6.22 milliseconds, or about 161 times a second, blasting its planets with an intense beam of deadly radiation that can be detected from Earth.

It's little wonder the pulsar has picked up the nickname "Lich" after a powerful and evil undead creature of the same name in fantasy.

A survey of 800 pulsars over the past 50 years carried out by researchers at Britain's Jodrell Bank Observatory has revealed that only 0.5% of pulsars host planets with masses similar to Earth. The researchers' results were published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The finding deepens the mystery of how planets can survive around pulsars which, like all neutron stars, form when massive stars reach the end of nuclear fusion and the outward pressure that supports them against gravitational collapse ceases.

The resultant collapse creates a massive supernova explosion, often powerful enough to outshine every star in the galaxy that hosts them. Ultimately this leaves behind a neutron star with a mass similar to that of the sun within a radius similar to that of a city on Earth. Neutron stars consist of the densest known matter in the universe: just a teaspoon of this matter would weigh 8 trillion pounds (3.6 trillion kilograms).

Pulsars are a special type of neutron star that blasts out bright radio wave radiation due to their rapid rotation and powerful magnetic fields.

"[Pulsars] produce signals which sweep the Earth every time they rotate, similarly to a cosmic lighthouse," University of Manchester Ph.D. student Iuliana-Camelia Nițu said in a statement. "These signals can then be picked up by radio telescopes and turned into a lot of amazing science."

While many pulsars have been found to host exotic worlds unlike anything found in the solar system, the violent conditions that surround the births of pulsars and their continued existence seem to make the formation of Earth-like planets around them unlikely.

Related: The 10 most Earth-like exoplanets

Nițu was part of a team of astronomers from the University of Manchester that performed the largest search of planets around pulsars to date, focusing on planets with masses up to 100 times that of the Earth, and orbital time periods between 20 days and 17 years.

They made ten potential detections of such worlds, with the system most likely to host exoplanets of this nature being PSR J2007+3120. The team believes that this pulsar, located 17,000 light-years from Earth, could host two planets with masses a few times that of Earth and with orbital periods of between 1.9 and around 3.6 years respectively.

The astronomers didn't find enough information to say that planets around pulsars share similar masses and orbital periods, but they do appear to have something else in common: The exoplanets around the pulsars investigated appear to have highly elliptical orbits, unlike the near-circular orbits of planets in the solar system.

This could indicate that however planets around pulsars form, these processes differ from the mechanism that led to the formation of planets in the solar system.

"Pulsars are incredibly interesting and exotic objects. Exactly 30 years ago, the first extrasolar planets were discovered around a pulsar, but we are yet to understand how these planets can form and survive in such extreme conditions," Nițu said in a statement. "Finding out how common these are, and what they look like is a crucial step towards this."

The research will be presented on July 12 at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM 2022).

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.