How to spot the 'elusive' planet Mercury in the night sky this month

For the next two and a half weeks, early-morning skywatchers will have an excellent opportunity to spot the so-called "elusive planet" — Mercury.

Two planets are closer to the sun than Earth is — Venus and Mercury — and are known as the "inferior" planets. Venus orbits the sun once every seven and a half months and gains a whole lap on the slower-moving Earth every 584 days. Venus is an evening object for about nine months until it passes behind the sun, then a morning object for nine months as it moves between the sun and Earth. And right now, Venus is a very prominent, albeit low, beacon in the southwest sky soon after sunset.

Related: 10 strange facts about Mercury

Now is Mercury's time

But while many people have seen Venus, not so many have ever noticed Mercury. Scarcely more than half the distance from the sun as Venus is, Mercury doesn't venture far from the sun in the sky, dodging out into view in the evening twilight low in the west, or in the east before sunrise.

But at certain times of the year the planet is easy to spot if you know when and where to look — and now is one of those times.

Mercury is the fastest and smallest of the major planets (it's only 1.4 times wider than our moon). It orbits the sun just over four times per year, but from our moving perspective on Earth it appears to go around a little over three times. Each year it makes about three and a half swings into the morning sky and as many into the evening — excursions of highly unequal character because of its eccentric orbit and the varying angles from which we view it.

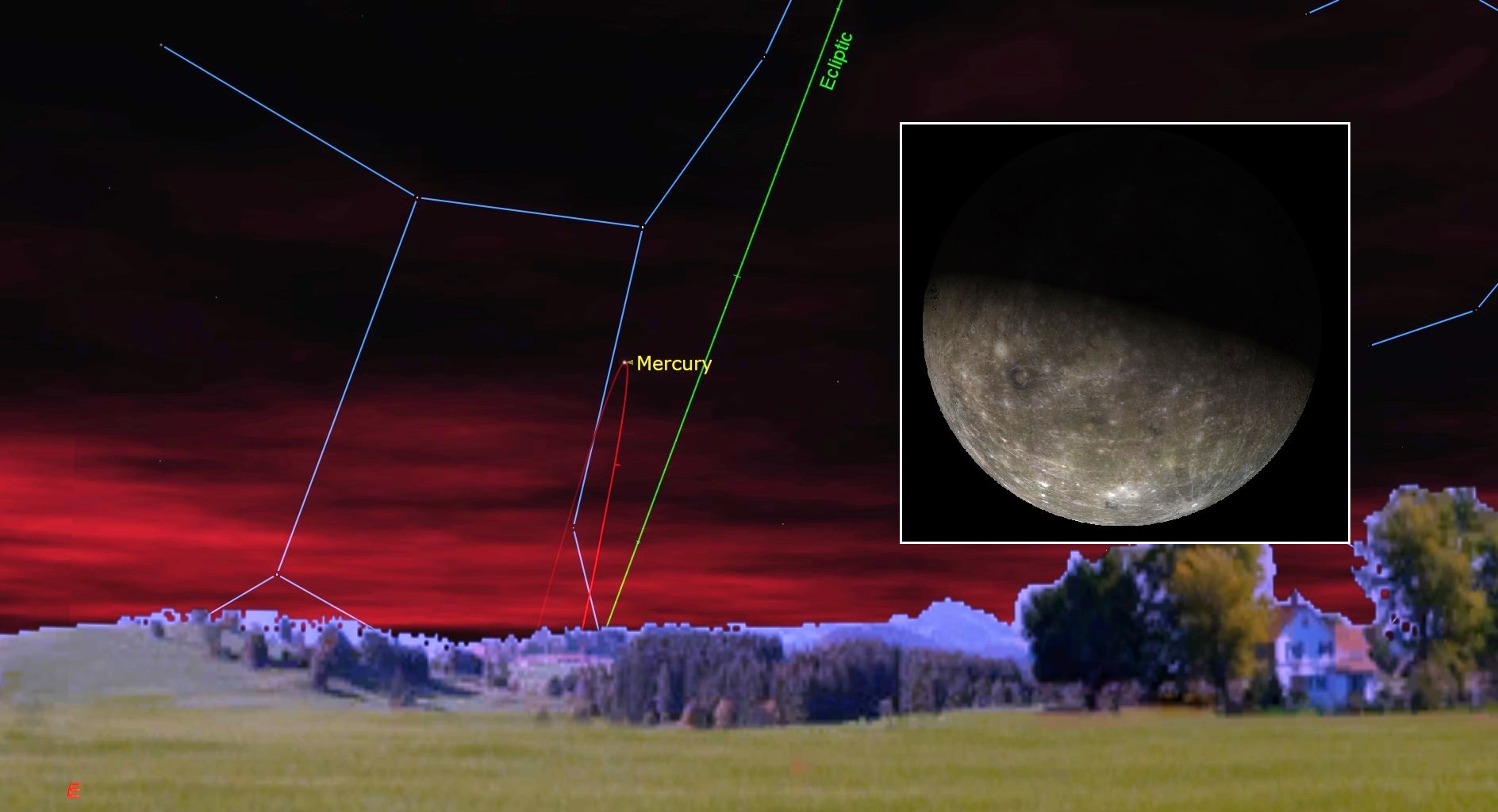

As a rule, the best chances to make a Mercury sighting in the evening come during the spring, and in the morning during the fall. At these times, the ecliptic — the imaginary path for the sun, moon and planets against the background of stars — stands nearly perpendicular relative to the western evening horizon in the spring, and the morning eastern horizon in the fall. As a result, after conjunction with the sun, Mercury appears to vault into view over a very short interval of time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury ascends

Take for instance, the current apparition.

On Oct. 9, Mercury was at inferior conjunction, meaning it was positioned almost directly between us and the sun, so it could not be seen. On Oct. 14, Mercury rose about 45 minutes before sunrise, but at magnitude +2.5 the speedy little planet was impossible to see in the brightness of dawn. But on Oct. 17, just three days later, Mercury was rising 1 hour and 20 minutes before the sun, having brightened to first magnitude, and was visible through binoculars above the horizon a bit to the south (right) of due east about 40 minutes before sunrise.

After Oct. 17, Mercury's overall visibility improves rapidly. On Saturday morning (Oct. 23) it will rise 2 minutes before morning twilight begins and will have brightened markedly to magnitude -0.4. Among the stars, only Sirius and Canopus will shine brighter.

An unusually favorable greatest elongation will occur on Monday (Oct. 25), even though Mercury is only 18 degrees from the sun. At magnitude -0.6, it will rise in a dark pre-twilight sky. Through a telescope, the tiny disk of Mercury will appear 57% sunlit. One hour before sunrise, it will be near-impossible to miss with the unaided eye: a very bright yellowish-orange "star" shining alone, low above the east-southeast horizon. The only object you might get it confused with is the similarly hued star Arcturus, which will be at a similar altitude but shining above the east-northeast horizon, about 30 degrees to the east (left) of Mercury. A clenched fist at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees in width, so on that morning, Arcturus will glow roughly "three fists" to the left of Mercury.

After that, Mercury gradually turns back toward the sun, but it brightens slightly as its phase waxes toward full. On Nov. 3, having brightened to magnitude -0.9, look low to the east-northeast horizon about an hour before sunrise and you'll see Mercury forming a right triangle with the waning crescent moon and the blue first-magnitude star Spica. The moon will hover 3.5 degrees above Mercury, while Spica twinkles 4 degrees to Mercury's right. You might, however, need your binoculars to spy Spica against the brightening twilight sky.

Why does it happen?

There are three reasons for the rapid reappearance of Mercury after the conjunction of Oct. 9:

- At sunrise in autumn, the ecliptic makes a steeper-than-average angle with the horizon for Northern Hemisphere observers.

- Because Mercury passes the ascending node of its orbit on Oct. 15, it is north of the ecliptic in late October and early November.

- Its orbital speed is near maximum, because perihelion (its closest passage to the sun) occurs on Oct. 18. Around inferior conjunction, Mercury is much closer to Earth, and its angular motion relative to the sun is much greater than around superior conjunction.

The rapid changes in Mercury's brightness and its rising time relative to the sun's make it possible to predict within a day or two when Mercury will last be visible to the unaided eye before it disappears into the bright glow of dawn twilight. My guess is Nov. 7. Can anyone still see it after that date?

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.