The $8.9 billion James Webb Space Telescope may be the last big-budget observatory that NASA launches for a while.

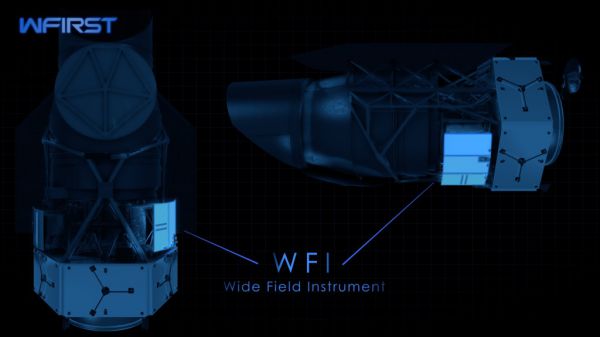

The White House's proposed 2020 budget cancels the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), a $3.2 billion space mission viewed as a linchpin of astrophysics research through the 2020s and beyond.

And that budget keeps NASA's astrophysics funding so low over the coming years that the agency won't be able to develop another ambitious, big-ticket "flagship" observatory for the foreseeable future, experts say.

Related: NASA Weighs Delaying WFIRST to Fund JWST Overrun

"If that budget is really the budget, there are not going to be future flagships," said David Spergel, a Princeton University theoretical astrophysicist, who co-chairs the WFIRST science team.

"We will have JWST — a wonderful observatory — and that's it," said Jon Morse, who led NASA's Astrophysics Division from 2007 to 2011. He now serves as CEO of the BoldlyGo Institute, a nonprofit devoted to developing space-science missions.

JWST, billed as the successor to NASA's iconic Hubble Space Telescope, is currently scheduled to lift off in May 2021, after multiple delays and significant cost overruns.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A bleak budget for astrophysics

The 2020 federal budget proposal, which the White House unveiled last week, allocates $21 billion to NASA — about $500 million less than the space agency is getting this year.

The agency's science funding was particularly hard-hit, dipping from $6.9 billion this year to $6.3 billion in 2020. Much of the decrease comes in astrophysics, which drops from $1.19 billion to $845 million. (That doesn't count the $353 million allocated next year to JWST, which has its own funding line.)

Astrophysics funding stays relatively flat in the proposed "out years," ranging from $902 million to $965 million between 2021 and 2024.

That's not nearly enough money to maintain a diverse and balanced research portfolio that includes small, medium-class and flagship missions, Morse said.

"By design, in this budget request, you can't fit a multibillion-dollar observatory into the remaining budget," he told Space.com. "That's why they canceled WFIRST — they took away the money. There's no money to execute a mission that costs $3 billion over seven or eight years."

Restoring the flagship capability would require, at a minimum, bumping the 2020 astrophysics budget up by $400 million — the amount "saved" with the cancellation of WFIRST, Morse said.

A powerful space observatory

WFIRST was pegged as the highest-priority large space mission in the 2010 astronomy/astrophysics decadal survey. Decadal surveys, which are put together every 10 years by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, serve as research roadmaps for government agencies such as NASA; their recommendations are usually followed.

WFIRST remains on budget and on schedule for its planned 2024 launch, Spergel said. The observatory features a main mirror 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) wide, the same size as Hubble's. But WFIRST will have a field of view 100 times greater than that of Hubble.

WFIRST will have two science instruments, which will allow the observatory to perform a variety of groundbreaking astronomical investigations. For example, astronomers will use WFIRST to characterize dark energy — the mysterious force behind the universe's accelerating expansion — as never before, discover thousands of exoplanets and image some alien worlds directly.

Related: What Is Dark Energy?

The widely surveying WFIRST was also specifically designed to complement JWST, which will investigate narrower slices of sky more deeply, Morse said.

So, axing WFIRST would deal a serious blow to astronomy, astrophysics and the scientific enterprise as a whole, he added. And the step back from big and bold space telescopes that WFIRST's cancellation seems to portend would also threaten the United States' position as a space-science leader, both he and Spergel said.

"If we stop doing astrophysics flagships, we stop leading," Spergel told Space.com.

That's because flagships tend to be incredibly productive and influential. Think about Hubble, which launched to Earth orbit in April 1990. The contributions of that famous space telescope are too numerous to rattle off here, but they include helping astronomers discover dark energy and bringing the beauty and mystery of the universe to lay people around the world with the most gorgeous cosmic photos ever taken.

Hubble is still going strong, but it's been showing some signs of age recently. NASA's other operational flagship-class space telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, is also getting long in the tooth; it launched in 1999.

Everyone hopes that JWST will conduct great science for many years to come. But there are no guarantees in that regard, and a bare flagship cupboard after JWST's 2021 launch is a depressing prospect for both Spergel and Morse.

Morse invoked the current high-energy-physics landscape as a cautionary tale.

The United States had a chance to cement itself as a particle-physics leader for decades to come in the 1990s with the construction of the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) in Texas. But funding for that project was pulled, and Europe ended up taking the mantle in 2010 with the completion of the Large Hadron Collider (which, though extremely capable, is far smaller and less powerful than the SSC was going to be).

"Is that where we're headed with astrophysics after launching JWST?" Morse said.

Not set in stone

But there is still hope for WFIRST, and for future flagships that may follow in its footsteps. The 2020 federal budget request is just that, after all — a request. An enacted budget must have congressional approval, and Congress has stood up for WFIRST before.

Indeed, the White House cut the mission in its 2019 budget request as well, but Congress stepped in and restored funding.

Both Spergel and Morse would love to see history repeat itself.

"Congress has had strong bipartisan support for astrophysics," Spergel said. "I'm hopeful these cuts in astrophysics will be overturned."

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.