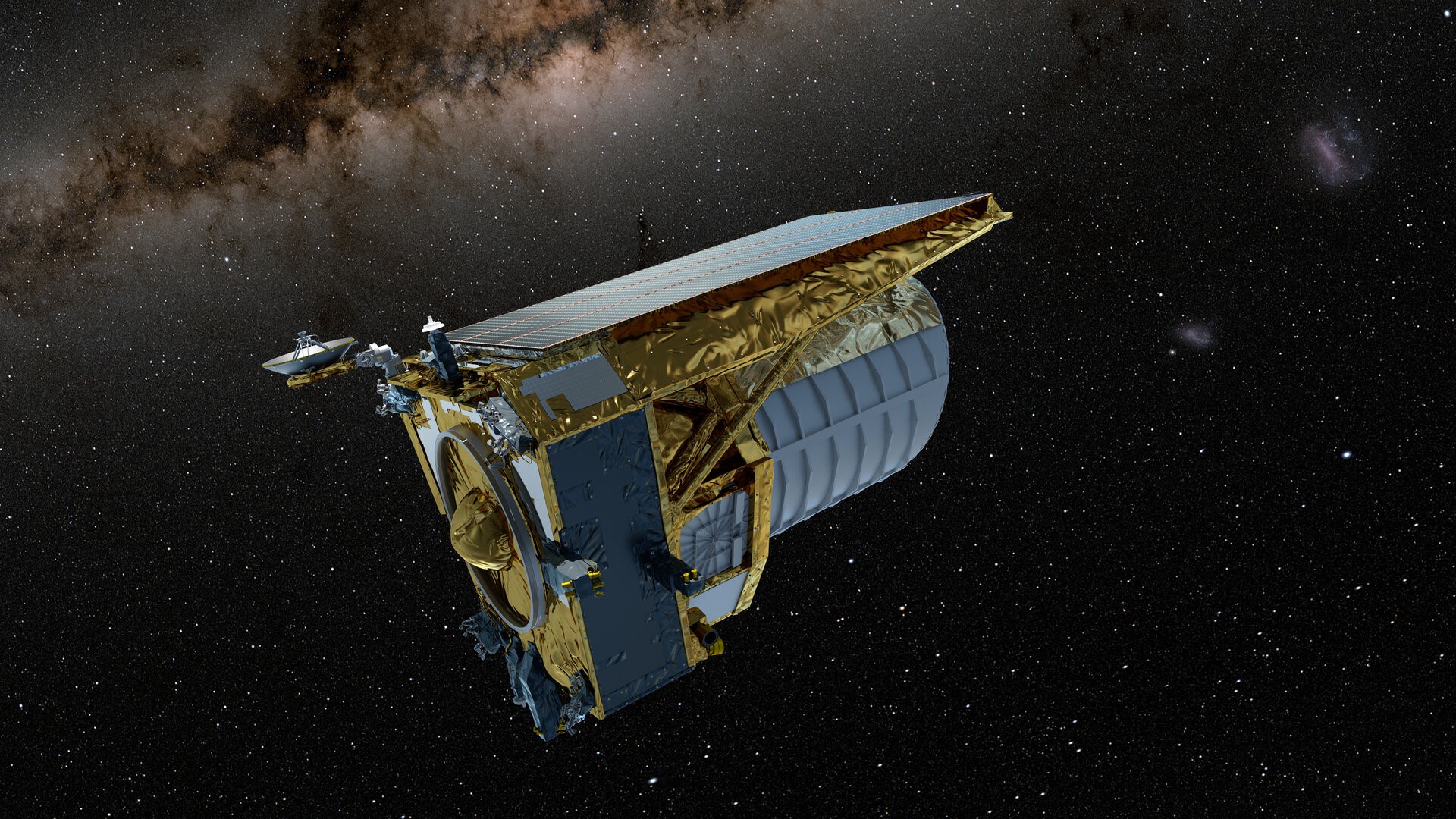

Euclid 'dark universe' telescope gets de-iced from a million miles away

"De-icing should restore and preserve Euclid's ability to collect light from these ancient galaxies, but it's the first time we're doing this procedure."

Just like drivers scrape ice from car windshields during the winter, scientists with the European Space Agency's (ESA) Euclid observatory are trying to "de-ice" the telescope — from a million miles away.

Ice layers, about as wide as a single DNA strand, have accumulated on Euclid's mirrors. Although small, the ice appears to have caused "a small but progressive decrease" in the amount of starlight the telescope is capturing, the agency said in a statement on March 19 (Tuesday). The telescope continues its science observations for now while scientists begin heating low-risk optical parts of the spacecraft to begin a de-icing process. These low-risk areas correspond to sections on the telescope where released water is unlikely to impair other instruments, the agency said.

Related: Euclid 'dark universe' telescope reveals its 1st sparkling images of the cosmos (photos)

"De-icing should restore and preserve Euclid's ability to collect light from these ancient galaxies, but it's the first time we're doing this procedure," said Reiko Nakajima, a Euclid scientist at the University of Bonn in Germany. "We have very good guesses about which surface the ice is sticking to, but we won't be sure until we do it."

The problem is not entirely uncommon for space telescopes. Scientists know it is close to impossible to prevent miniscule amounts of water in the air from making its way into spacecraft during assembly, so "it was always expected that water could gradually build up and contaminate Euclid's vision," ESA said in Tuesday's statement.

Shortly after Euclid's launch in July of last year, scientists had warmed the telescope using onboard heaters to evaporate most of the water molecules that would have entered the spacecraft prior to liftoff. But it appears "a considerable fraction" survived, perhaps by being absorbed into the telescope's multiple layers of insulation, which have gotten loose since reaching the vacuum of space. In space's frigid environment, these molecules tend to stick to the first surface they land on, one of which appears to be the telescope's mirrors.

The issue first came to light when the mission team noticed a gradual decrease in starlight measured with one of Euclid's two science instruments, called the visible instrument (VIS). To help catalog 1.5 billion galaxies and their stellar populations, VIS collects visible light from stars similar to how a smartphone camera operates, only with 100 times as many pixels. Its resolution is thus equivalent to a 4K screen.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Some stars in the universe vary in their luminosity, but the majority are stable for many millions of years," Mischa Schirmer, a Euclid scientist who is leading the de-icing campaign, said in the statement. "So, when our instruments detected a faint, gradual decline in photons coming in, we knew it wasn't them — it was us."

The easiest solution would be to heat the entire spacecraft, but doing so would also warm up the telescope's mechanical structure, whose components would expand but not necessarily return to their original states even after a week, the mission scientists say. That would limit Euclid's vision and, in turn, impact the quality of data it gathers. The telescope is influenced by even the tiniest of temperature changes. So, Schirmer and her colleagues are planning to first heat up low-risk, optical parts of Euclid, starting with two mirrors that can be warmed independently of one another and then monitor how the change influences the amount of light VIS gathers.

This icy dilemma marks the second problem with the spacecraft in one year. Last September, a sensor meant to find stars for navigation purposes incorrectly tagged cosmic rays as stars, meaning the telescope couldn’t resolve the star patterns it relied on to point itself at specific areas in the sky. The issue was fixed a month later.

As for the latest issue, scientists expect tiny amounts of water to continue being released over Euclid's six-year life in orbit. So if they are successful with the de-icing campaign this time, the same procedure could keep Euclid's systems ice-free for the rest of its mission.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social