James Webb Space Telescope detects 1st evidence of carbon on Jupiter's icy moon Europa

The discovery made using NASA's powerful space telescope brings scientists a step closer to determining if the salty water oceans of Europa could support life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The James Webb Space Telescope has identified carbon dioxide originating from the salty liquid oceans of Jupiter's icy moon Europa.

Scientists have been aware for some time that oceans of water lie beneath the icy shell of Europa but did not know if these oceans had the right chemistry to support life. Thus, the discovery of carbon — a vital element in living things — from this subsurface ocean on one of Jupiter's moons has important implications for the potential habitability of this moon and is a testament to the groundbreaking science being made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

"On Earth, life likes chemical diversity — the more diversity, the better. We're carbon-based life. Understanding the chemistry of Europa's ocean will help us determine whether it's hostile to life as we know it or whether it might be a good place for life," research lead author and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center scientist Geronimo Villanueva said in a statement. "This suggests that we may be able to learn some basic things about the ocean's composition even before we drill through the ice to get the full picture."

Related: Surprise! Jupiter's ocean moon Europa may not have a fully formed core

Even more exciting, the team was able to use observations made in infrared with the JWST's Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument to determine that the carbon molecules were not delivered to Europa via meteorite impacts or other external sources.

"We now think that we have observational evidence that the carbon we see on Europa's surface came from the ocean. That's not a trivial thing. Carbon is a biologically essential element," lead author of a second paper detailing this discovery and Cornell University researcher Samantha Trumbo said.

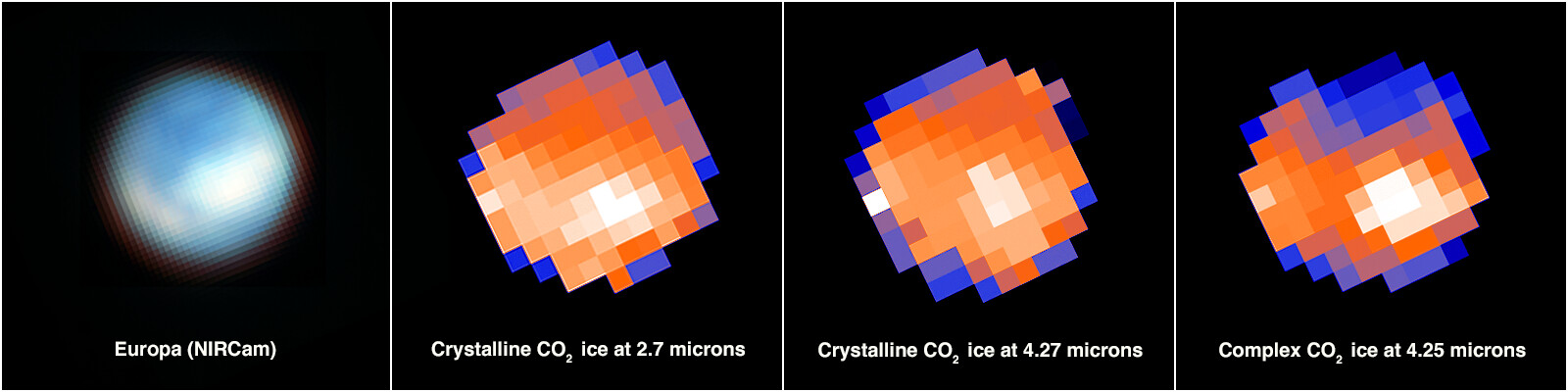

The JWST observed that the carbon dioxide around Europa, the smallest of the four large Galilean moons of Jupiter, is most abundant in a geologically young region called Tara Regio. Surface ice has been disrupted at this so-called "chaos terrain" area, indicating that material has been exchanged between Europa's icy surface and its subsurface ocean.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope show evidence for ocean-derived salt in Tara Regio," Trumbo continued. "Now we're seeing that carbon dioxide is heavily concentrated there as well. We think this implies that the carbon probably has its ultimate origin in the internal ocean."

The detection of carbon dioxide on Europa will be slightly bittersweet for Villanueva and his team, who were also using the JWST to hunt for plumes of matter erupting from the surface of the Jovian moon, something the powerful space telescope failed to see.

The plumes were tentatively detected in 2013, 2016, and 2017, and the fact the JWST failed to confirm their existence doesn't mean they aren't present around Europa.

"There is always a possibility that these plumes are variable and that you can only see them at certain times," Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, JWST interdisciplinary scientist Heidi Hammel said. "All we can say with 100% confidence is that we did not detect a plume at Europa when we made these observations with the JWST."

Nevertheless, the observation of carbon dioxide on Europa is a testament to the power and utility of the James Webb Space Telescope.

"These observations only took a few minutes of the observatory's time," Hammel, who leads the JWST's Cycle 1 Guaranteed Time Observations of the Solar System, added. "Even in this short period of time, we were able to do really big science. This work gives a first hint of all the amazing solar system science we'll be able to do with the JWST."

The findings have important ramifications for other missions in the future, as well. In October 2024, NASA will launch the Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will journey to the Jovian moon system to conduct a detailed survey of Europa to determine if its subsurface oceans could support life.

The JWST findings from these two teams could also help inform the investigation of Jupiter and its moons by the European Space Agency (ESA) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission. JUICE was launched in April 2023 on a 7.5-year journey to Europa and its fellow large Jovian satellites, Callisto and Ganymede, which both also bear vast oceans, as well as making important observations of Jupiter itself.

"This is a great first result of what the JWST will bring to the study of Jupiter's moons," research co-author and ESA Research Fellow Guillaume Cruz-Mermy said. "I'm looking forward to seeing what else we can learn about their surface properties from these and future observations."

The two teams' research was published in two papers in the Sept. 21 edition of the journal Science.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.