A European satellite made spaceflight history on Friday (July 28).

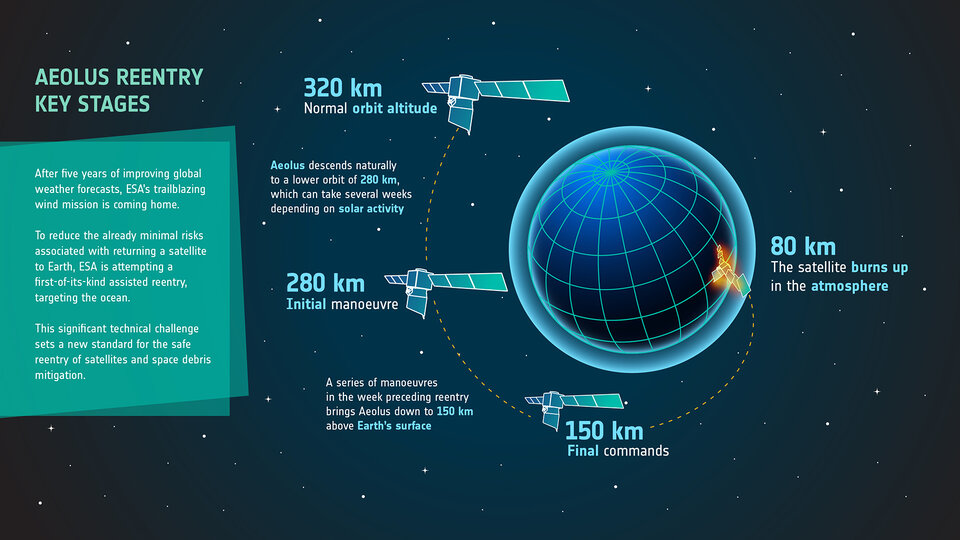

The European Space Agency's (ESA) Aeolus spacecraft reentered Earth's atmosphere at around 3 p.m. EDT (1900 GMT) over Antarctica, according to the mission team. The fall capped a four-day orbit-lowering campaign that could blaze a new trail for satellite operators.

"This is quite unique, what we're doing. You don't find really examples of this in the history of spaceflight," Holger Krag, head of ESA's Space Debris Office, said during a press briefing on July 19. "This is the first time to our knowledge [that] we have done an assisted reentry like this."

Related: When and where will Europe's Aeolus wind satellite fall to Earth this week?

🌠🎯🇦🇶 CONFIRMED in the early hours, #Aeolus reentered Earth’s atmosphere on 28 July at around 21:00 CEST above Antarctica.✅ by US Space Command.Read more about the historic, pioneering end to a trailblazing mission👉https://t.co/WxVaqTlS8f#ByeByeAeolus#SustainableSpace pic.twitter.com/HHEn3fhZNCJuly 29, 2023

Aeolus was a pioneer in life as well. The 3,000-pound (1,360 kilograms) satellite launched in August 2018 to monitor Earth's winds, something that had never been done in detail from orbit.

The spacecraft's data helped researchers improve their climate models and weather forecasts, ESA officials have said. And there is more of this data than the mission team expected: Aeolus operated for nearly 4.5 years, about 18 months longer than its planned scientific lifetime.

But the spacecraft eventually began running low on fuel. Rather than let Earth's atmosphere drag Aeolus down in a chaotic fashion, as is the norm for orbiting satellites, mission team members decided to take a more active role in the spacecraft's demise. They orchestrated the de-orbit campaign, which aimed to ensure that Aeolus burned up over an unpopulated stretch of Earth's surface, posing no threat to people and buildings on the ground.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That threat, though small, is real whenever a satellite falls uncontrolled to Earth: In general, about 20% of a spacecraft's mass survives the fiery trip through the atmosphere and hits terra firma (or, more commonly, ocean waters). And there's a lot of stuff up there just waiting to come down.

"Today, we have 10,000 spacecraft in space, of which 2,000 are not functional. In terms of mass, we are speaking about 11,000 tons," Krag said at the July 19 press conference.

About 100 tons of human-made space junk fall to Earth each year, and large objects reenter our atmosphere about once a week on average, he added.

Guided reentries, which are commonly performed by rocket stages after orbital launches, could help make a dent in this space-junk problem. And the Aeolus team hopes to lead the way in this respect.

Aeolus' reentry campaign "sets a new precedent for safe spacecraft operations and sustainable spaceflight, for both future missions and those already in orbit," ESA's Rosa Jesse wrote in a blog post last month.

Aeolus studied Earth's winds from an altitude of about 200 miles (320 kilometers). The spacecraft began falling from this orbit on June 19, and the mission team started accelerating the process five weeks later.

On Monday (July 24), Aeolus performed two engine burns that lasted a total of 37.5 minutes and lowered its altitude by about 19 miles (30 km), to 155 miles (250 km). The campaign picked up again Thursday (July 27), with four planned orbit-lowering maneuvers.

One final maneuver occurred Friday, which was expected to set the stage for reentry about five hours later. And that appears to have gone mostly according to plan.

We see more efforts like this from other satellite operators going forward.

Aelous' deorbit campaign "paves the way for the safe return of active satellites that were never designed for controlled reentry," ESA's Peter Bickerton wrote in a July 19 blog post.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

-

Ryan F. Mercer The article never mentions *how* the craft is being decelerated for reentry. I assume it's using it's own thrusters and remaining fuel. Thus I am confused as to why this has never been attempted before, or what about this first instance will provide anything relevant to those who follow. They have a craft with fuel and are doing a retro burn to cause reentry. How is this new? How will it provide new knowledge?Reply

Also, obviously, this means nothing for deactivated craft running on empty. I'm still trying to understand what the news is here. -

Unclear Engineer From the article, I think the thrust of the on-board rocket is not enough to do a fast deceleration so that they can be relatively sure where the reentry will occur, given the variability of drag in time and location where the atmosphere thins out.Reply