Europe's new Ariane 6 rocket has finally taken flight, carrying the hopes of a continent on its broad back.

The Ariane 6 launched for the first time ever today (July 9), lifting off from Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, at 3:01 p.m. EDT (1901 GMT).

There was a lot riding on this debut: It came a year after the retirement of Ariane 6's predecessor, the workhorse Ariane 5, left Europe unable to launch big satellites on homegrown rockets.

"Ariane 6 will power Europe into space. Ariane 6 will make history," Josef Aschbacher, the director general of the European Space Agency (ESA), said via X today in the leadup to launch.

A brand-new rocket

Today's launch was a long time coming. Development of the Ariane 6 began in late 2014, and its debut was originally envisioned to take place in 2020. But the timeline slipped due to technical issues and outside problems, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The delays meant that the Ariane 6 did not overlap with the Ariane 5, which flew 117 orbital missions from 1996 to 2023. The Ariane 5's retirement left Vega, a small-satellite launcher, as the only operational orbital rocket in Europe's stable.

That wasn't an acceptable situation for European space officials, who don't want to be dependent on SpaceX's workhorse Falcon 9 and other foreign rockets to loft their big payloads. So they'd been eagerly awaiting today's launch.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Ariane 6 "will ensure our guaranteed, autonomous access to space — and all of the science, Earth observation, technology development and commercial possibilities that it entails," ESA officials wrote in a preview of today's liftoff.

Related: The history of rockets

The two-stage Ariane 6 is built by the French company ArianeGroup and operated by its subsidiary Arianespace on behalf of ESA. The rocket's first stage is powered by a single Vulcain 2.1 engine — an evolved variant of the Ariane 5's Vulcain 2 — and its upper stage features one Vinci engine, which is new technology. (The Ariane 5's upper stage sported one Aestus engine, or one HM-7B.)

The Ariane 6 comes in two variants: the A62, which has two strap-on solid rocket boosters (SRBs), and the A64, which has four SRBs. The A62 and A64 can deliver about 11.4 tons (10.3 metric tons) and 23.8 tons (21.6 metric tons) to low Earth orbit (LEO), respectively, according to ESA.

That latter figure is comparable to the Ariane 5's payload capacity. But the Ariane 6 will do the job for about half the price of its predecessor, thanks to manufacturing improvements and other advances, European officials have said.

Those prices are murky, however; Arianespace has been cagey about its per-flight costs, so all we have are estimates. Late last year, Ars Technica pegged the baseline price of an Ariane 5 launch at about 150 million euros ($162 million US at current exchange rates), which would put the target price of an Ariane 6 mission at 75 million euros ($81 million US).

As Ars noted, that would make the new rocket "reasonably competitive" with the market's dominant launcher, the Falcon 9, which can be booked for $67 million per flight. But there's more to the story: ESA's member states have committed to subsidize the Ariane 6, to the tune of 290 million to 340 million euros ($314 million to $368 million US) per year through 2031 or so. So the actual per-launch cost will likely be considerably higher than what Ariane 6 customers are paying.

The Falcon 9, as most folks know, is partially reusable: Its first stage comes back to Earth for recovery, refurbishment and reflight. But the Ariane 6, like the Ariane 5 before it, is expendable. This design decision makes sense, given that the new rocket will likely fly a maximum of 10 times or so per year for the foreseeable future, ESA officials have said.

"Our launch needs are so low that it wouldn't make sense economically," Toni Tolker-Nielsen, ESA's director of space transportation, told SpaceNews recently, referring to reusability. "So, we don't really need it at this point."

The Ariane 6 already has 30 flights on its manifest, Tolker-Nielsen added, 18 of which will help build out Amazon's new Kuiper satellite-internet constellation. The new rocket will likely fly one more mission this year, then ramp up to six flights in 2025, eight in 2026 and 10 in 2027, he said.

But that's getting ahead of ourselves quite a bit. First, the rocket had to complete its debut flight successfully.

Related: Farewell, Ariane 5! Europe's workhorse rocket launches 2 satellites on final mission (video)

A 9-satellite debut

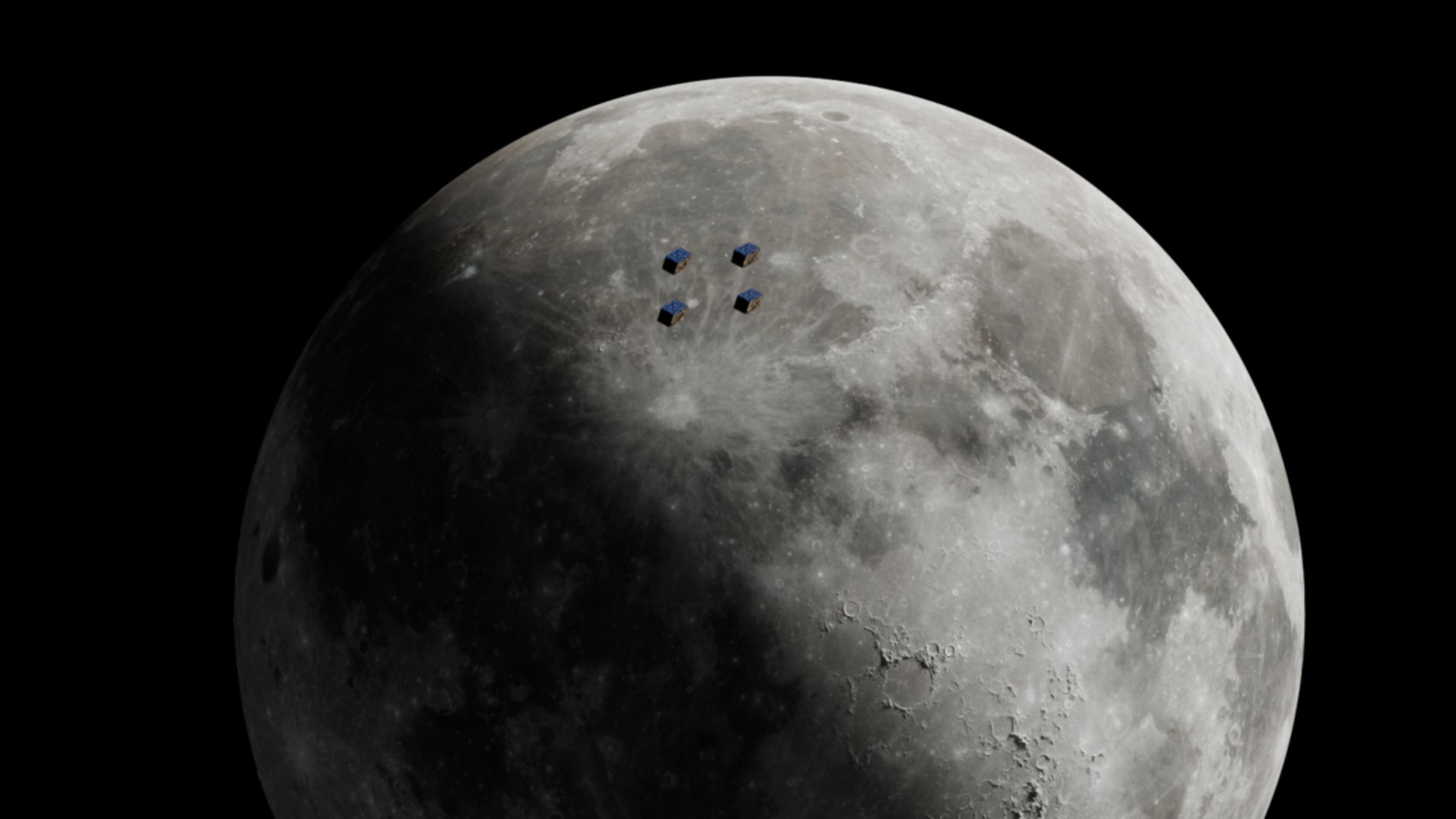

The Ariane 6 carried nine cubesats to orbit today. All of them were successfully deployed 370 miles (600 kilometers) above Earth about 65 minutes after liftoff as planned, European space officials said during a webcast of today's flight.

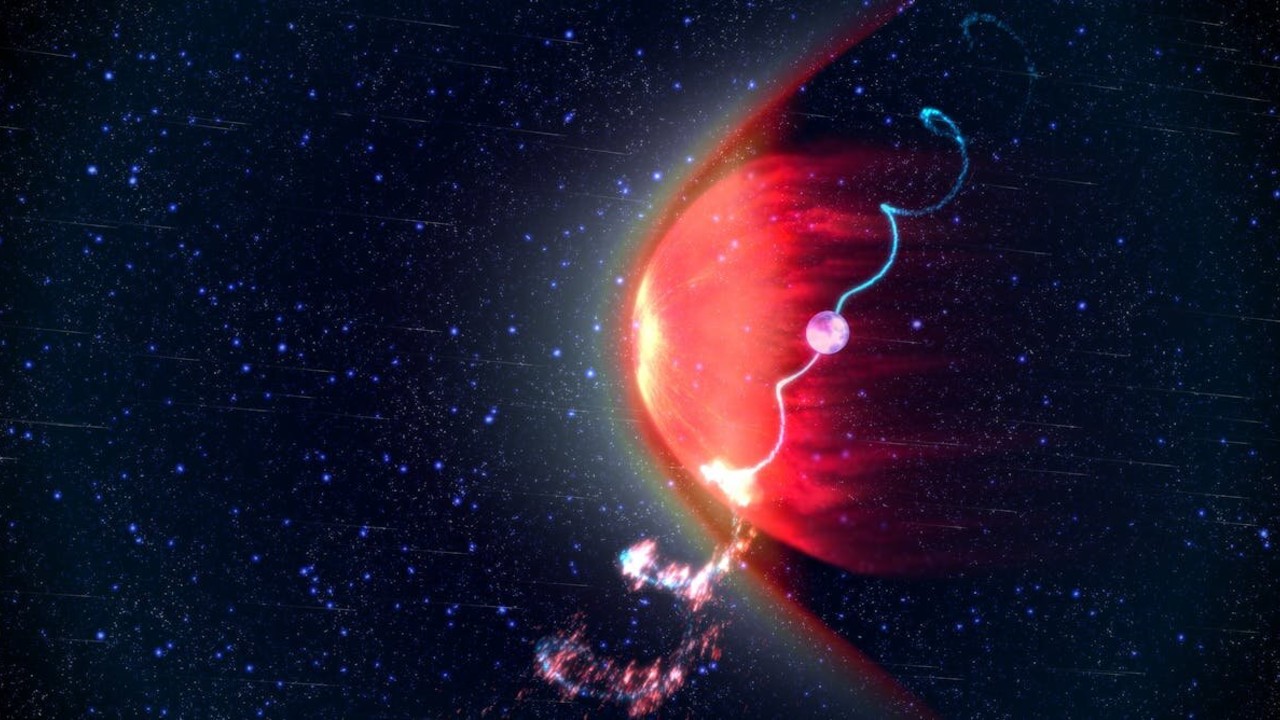

Two of those passengers make up NASA's Cubesat Radio Interferometry Experiment, or CURIE, which will attempt to determine the source of mysterious solar radio waves.

"This is a very ambitious and very exciting mission," CURIE principal investigator David Sundkvist, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a NASA statement. "This is the first time that someone is ever flying a radio interferometer in space in a controlled way, and so it's a pathfinder for radio astronomy in general."

The other cubesats will do a variety of work, from studying Earth's climate and weather to measuring highly energetic gamma rays. You can learn more about them via ESA here.

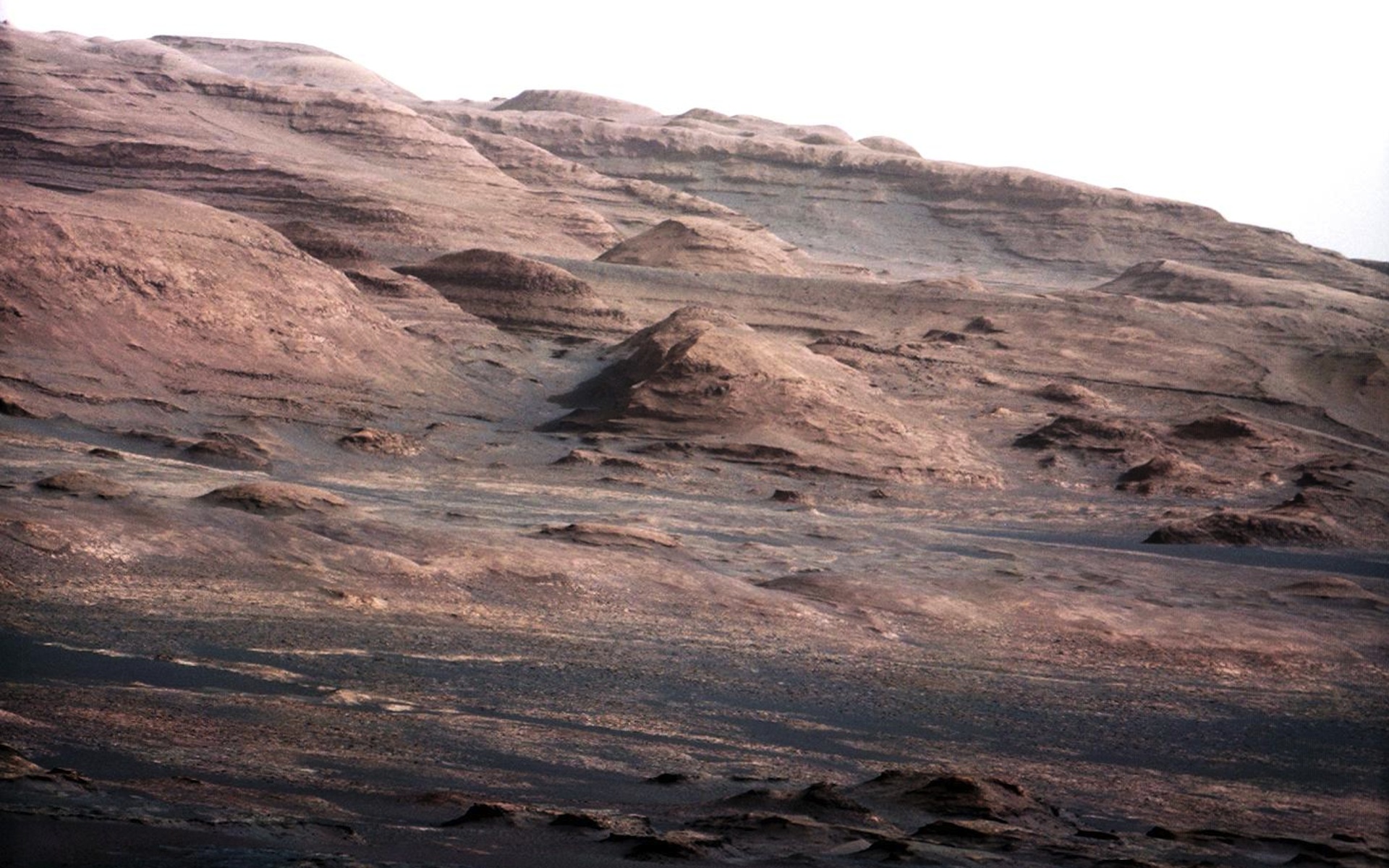

There was more scientific gear on today's flight as well, including several experiments that stayed attached to the Ariane 6's upper stage. The rocket was also supposed to deploy two experimental reentry capsules about two hours and 40 minutes into the flight. These two craft aimed to show that they can survive the fiery trip home through Earth's atmosphere.

That didn't happen, however; the Ariane 6's upper stage did not complete a burn designed to set up that final deployment. This was due to a failure with the auxiliary power unit (APU), a device that pressurizes upper-stage fuel tanks during flight and provides additional thrust as needed, according to ESA.

"At one point of time, we reignited the APU. It did reignite, and then it stopped," ArianeGroup CEO Martin Sion said in a postlaunch press conference today. "We don't know why it stopped. This is something that we will have to understand when we've got all the data."

But this anomaly, which occurred during the mission's "tech demo" phase, shouldn't overshadow the overall success of the flight, he and other mission team members said during the briefing.

"We are perfectly on track now to make a second launch this year, in 2024, for the French MoD, and to make the next missions," Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël said during the press conference. "So, it has no consequence on the next launches."

Editor's note: This story was updated at 7:45 p.m. ET on July 9 with news of successful cubesat deployment, the problem with the Ariane 6's upper stage and quotes from the post-launch press conference.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.