NASA's $5 billion Europa Clipper mission may not be able to handle Jupiter's radiation

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A highly anticipated NASA astrobiology mission is troubleshooting a serious issue just months before its planned liftoff.

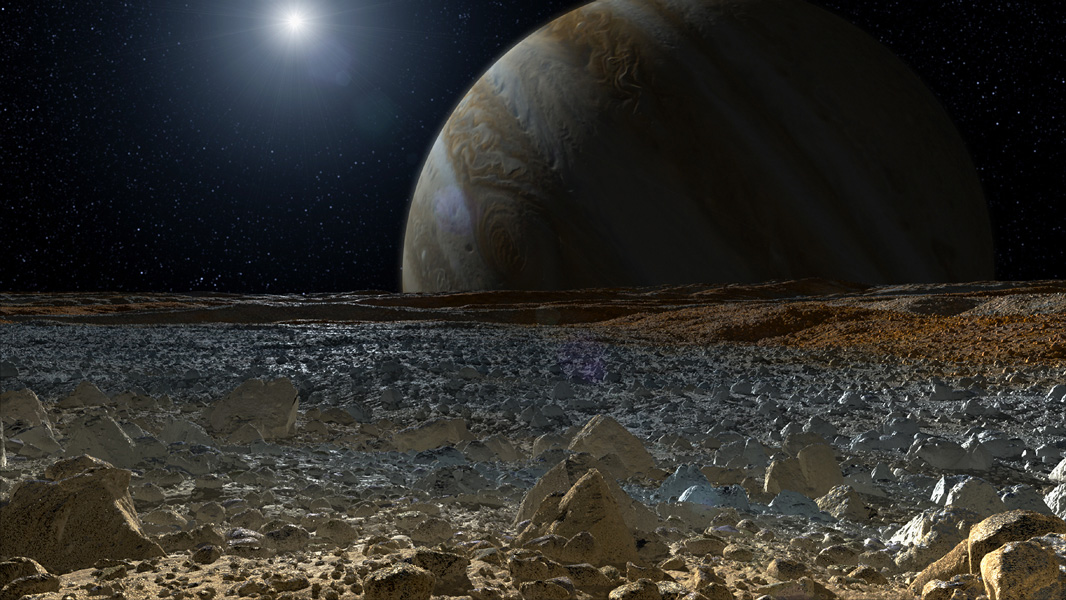

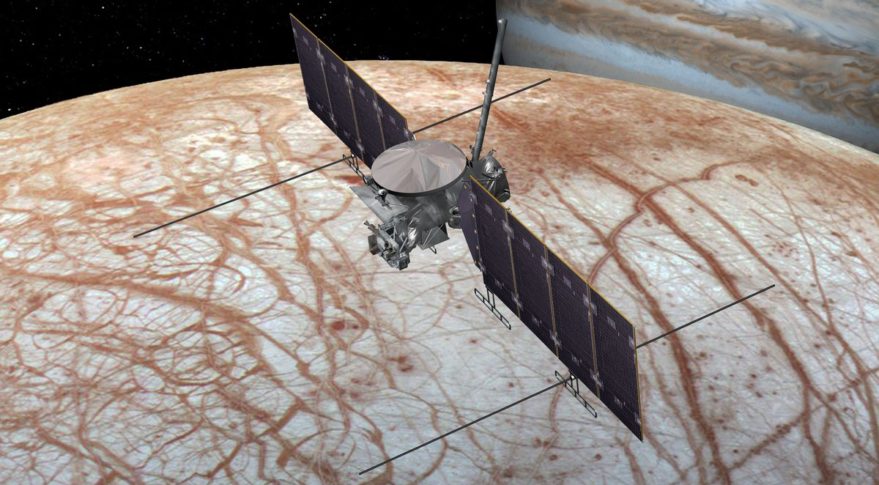

The Europa Clipper spacecraft is scheduled to launch this October atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. The robotic explorer will embark upon a $5 billion mission to assess the potential of Europa, an ice-covered ocean moon of Jupiter, to support life as we know it.

But that launch date, and the probe's ability to carry out its ambitious mission, may now be in peril: Mission team members have discovered a problem with Clipper's transistors, devices that control the flow of electricity on the probe.

"The issue with the transistors came to light in May when the mission team was advised that similar parts were failing at lower radiation doses than expected," NASA officials wrote in an update on Thursday (July 11).

That's of serious concern, because Clipper is headed into a radiation gauntlet.

"The Jupiter system is particularly harmful to spacecraft, as its enormous magnetic field — 20,000 times stronger than Earth's magnetic field — traps charged particles and accelerates them to very high energies, creating intense radiation that bombards Europa and other inner moons," NASA officials wrote in the update.

Europa Clipper is scheduled to arrive in the Jupiter system in 2030. The probe will orbit the gas giant, not Europa, but it will spend a fair bit of time in the moon's neighborhood: Clipper will make about 50 flybys of Europa over the course of its 3.5-year science mission.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Why NASA's Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter's icy moon is such a big deal

This past May, the mission team was told that parts similar to Europa Clipper's transistors "were failing at lower radiation doses than expected," NASA officials wrote in the Thursday update. Transistor testing is now underway at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which leads the mission, as well as the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, both of which are in Maryland.

The results aren't exactly promising.

"Testing data obtained so far indicates some transistors are likely to fail in the high-radiation environment near Jupiter and its moon Europa because the parts are not as radiation-resistant as expected," NASA officials wrote.

"The team is working to determine how many transistors may be susceptible and how they will perform in flight," they added. "NASA is evaluating options for maximizing the transistors' longevity in the Jupiter system. A preliminary analysis is expected to be complete in late July."

The devices in question are called metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors, or MOSFETs, and they were manufactured by a company called Infineon Technologies, according to the journal Science. The discovery of their vulnerability at this late stage makes it very difficult to deal with.

"The transistors cannot simply be replaced," Science's Paul Voosen wrote. "Clipper's aluminum-zinc electronics vault, meant to provide a measure of radiation resistance, was sealed in October 2023. Barring an indication that the faulty MOSFETs will cause catastrophic failure, the agency will likely seek to continue with the launch — although backup windows are available the next 2 years."

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.