Europe's first-ever Jupiter mission is officially underway.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) JUICE spacecraft launched atop an Ariane 5 rocket from Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana on Friday (April 14) at 8:14 a.m. EDT (1214 GMT), after a one-day delay caused by the threat of lightning at the launch site. Spacecraft separation occurred some 28 minutes after liftoff.

The liftoff kicked off an ambitious mission to study Jupiter and three of its biggest, most intriguing moons — Ganymede, Callisto and Europa, all of which are thought to harbor big liquid-water oceans beneath their icy shells.

"The main goal is to understand whether there are habitable environments among those icy moons and around a giant planet like Jupiter," planetary scientist and JUICE team member Olivier Witasse said during a press conference on April 6.

But the JUICE team and space fans around the world will have to be patient: The spacecraft won't make it to the Jovian system until 2031.

Related: Here's what the JUICE mission will teach us about Jupiter and its moons

A long trek through deep space

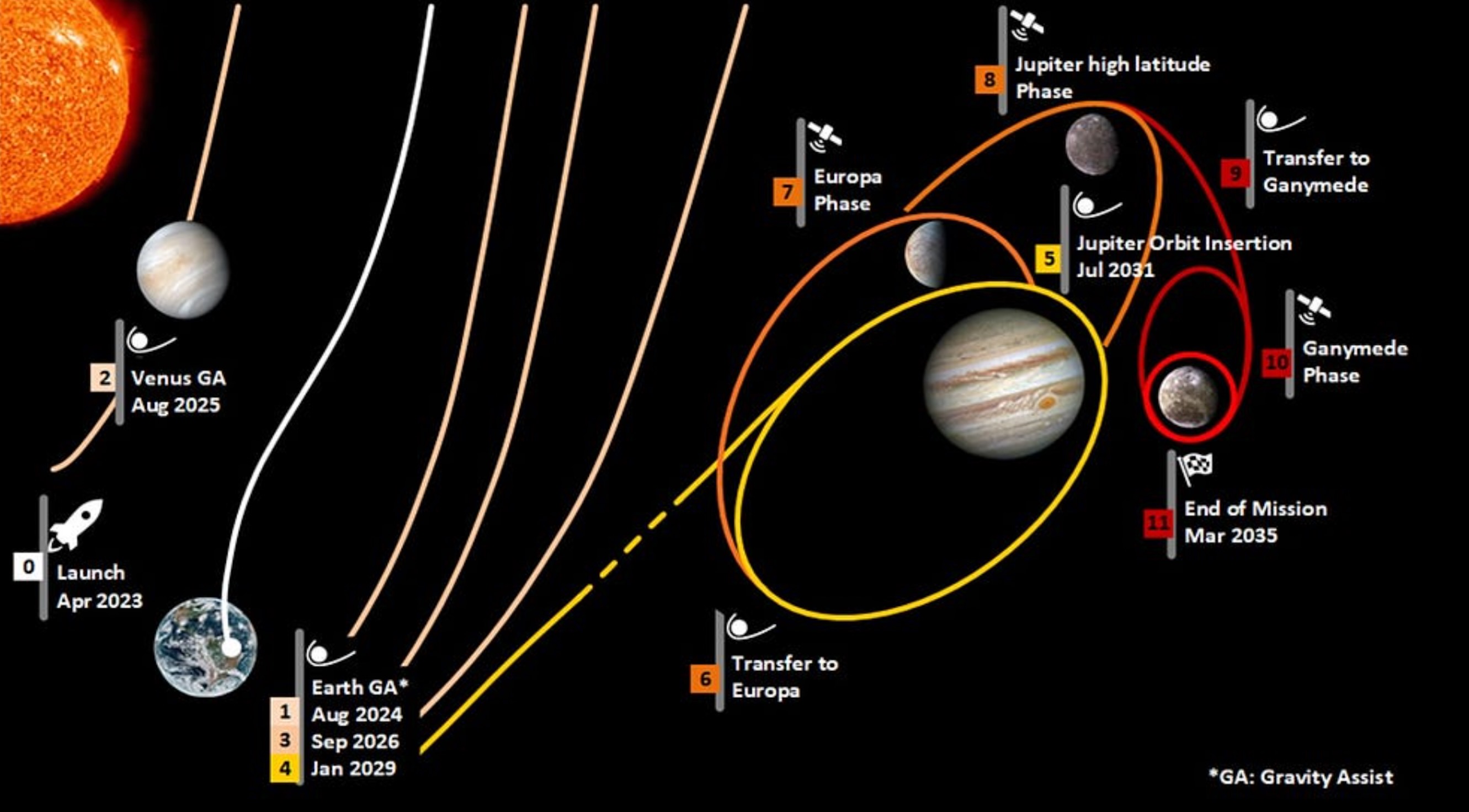

JUICE (short for "Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer") will take a circuitous, energy-efficient route to the king of planets, boosting its speed and honing its trajectory with the aid of four separate "gravity assist" planetary flybys.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The first of these slingshot encounters will take place in August 2024 and involve both Earth and its moon, with flybys of the two bodies separated by just 1.5 days. JUICE will be the first spacecraft ever to perform such a "lunar-Earth gravity assist," and pulling it off will be a challenge.

"This will be the most accurate gravity assist maneuver ever done," JUICE team member and ESA scientist Alessandro Atzei said during the April 6 briefing. "But this is, I think, under control."

JUICE will get its second gravity assist from Venus in August 2025, then swing by Earth for additional encounters in September 2026 and January 2029, if all goes according to plan.

After this final Earth encounter, the solar-powered probe will head toward Jupiter more directly, finally reaching the gas giant in July 2031. JUICE will then perform yet another flyby, this time of the huge Jovian moon Ganymede, to insert itself into orbit around Jupiter.

Studying Jupiter and three icy ocean moons

JUICE's science mission will begin even before it reaches Jupiter: About six months out from orbital insertion, the probe will start making observations of the Jovian system using its suite of 10 science instruments, which comprise "the most powerful remote sensing, geophysical and in situ payload complement ever flown to the outer solar system," according to ESA.

Those instruments include an optical camera system, spectrometers, a radar sounder, a laser altimeter, a magnetometer, and particle analyzers, among other gear.

The data collection will intensify once JUICE reaches Jupiter. The probe will study the gas giant in depth and also eye Ganymede, Callisto and Europa. Observations of the three moons will be made up close, over the course of 35 flybys between 2031 and 2034.

Twenty-one of these flybys will involve Callisto, which is the most heavily cratered world in the solar system, according to the nonprofit Planetary Society. JUICE will zip past Europa twice, hunting for possible pockets of liquid water just under its icy shell and looking for plumes of water vapor wafting from its surface. Scientists have gotten hints of such plumes in the past, but they've been difficult to pin down.

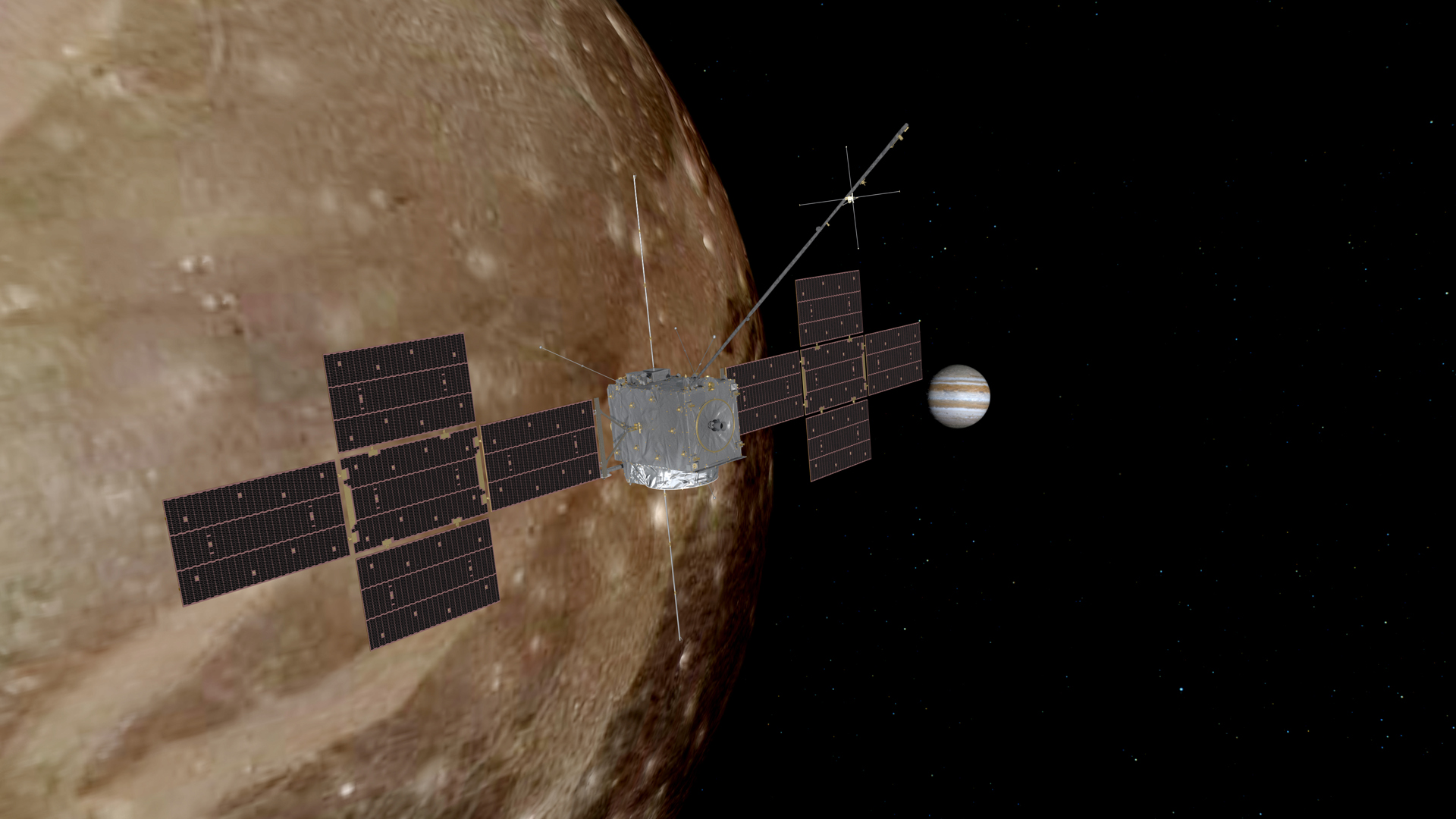

JUICE will fly by Ganymede a dozen times. Then, in December 2034, the probe will enter orbit around the 3,270-mile-wide (5,262 kilometers) moon, which is larger than the planet Mercury and is the only satellite known to possess a magnetosphere. This move will mark the first time a spacecraft has ever orbited a planetary moon other than that of Earth.

JUICE will continue to study Ganymede until its fuel runs out. The probe's orbit around the big moon will then begin to decay, and it will eventually crash-land onto Ganymede's icy surface, bringing the epic JUICE mission to a close.

The data gathered by the 1.6-billion-euro ($1.7 billion) mission should keep scientists in a variety of fields busy for years to come.

"JUICE will characterize Jupiter's ocean-bearing icy moons — Ganymede, Europa and Callisto — as planetary objects and possible habitats, explore Jupiter's complex environment in depth and study the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giants across the universe," ESA officials said.

"We have really a lot to do to satisfy the goals of the scientific community, but if I had one objective to highlight, it is the need to know more about the liquid water underneath the surface of the icy moons," Witasse added in the April 6 briefing. "It's quite fascinating to think that, underneath these icy surfaces, there is a lot of liquid water. And that will be really the most interesting aspect of the mission."

Ganymede, Callisto and Europa are three of Jupiter's four big Galilean moons, which are so named because they were discovered by famed Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in the early 1600s.

JUICE won't make an in-depth study of Io, the fourth and innermost Galilean moon. Io is not an icy ocean world; rather, it's the most volcanic body in the solar system, thanks to the gravitational pull of Jupiter and the three other Galilean moons, which stretches Io's interior and generates lots of frictional heat.

Related: The Galilean moons of Jupiter (photos)

A tough environment

Staying alive and productive in the Jupiter system won't be easy for JUICE, whose main body measures 13.4 feet by 9.4 feet by 14.3 feet (4.09 by 2.86 by 4.35 meters).

For starters, Jupiter orbits the sun about five times farther away than Earth does. Sunlight way out there is diffuse, so JUICE's solar panels need to be huge and efficient: After deployment, the cross-shaped arrays will cover a total area of 915 square feet (85 square m) and convert a whopping 30% of solar energy into electricity. Still, at Jupiter, the arrays won't even produce enough juice to power a hair dryer, mission team members have said.

In addition, Jupiter has a powerful magnetic field, which makes things difficult for spacecraft and mission planners. This field can affect sensitive scientific instruments directly. More worryingly, however, it also traps charged particles, creating a super-intense radiation environment at and around the giant planet.

High radiation levels are bad for electronics, so the JUICE team sealed the probe's most sensitive equipment in a lead-lined vault.

The radiation environment is less extreme around Ganymede than it is near Europa. That's part of the reason that the JUICE team chose to focus more of its efforts on the giant moon, even though Europa is a more intriguing astrobiological target. (And crash-landing into Europa at the end of the mission would have been more problematic, given the risk of contaminating a potentially life-hosting world with microbes from Earth.)

Another Jupiter mission coming

Just two missions have orbited Jupiter to date, both of them NASA efforts. The Galileo probe circled the giant planet from December 1995 to September 2003, and the Juno orbiter arrived in July 2016 and remains active today.

But JUICE won't be the next spacecraft to reach the gas giant, if all goes according to plan. That distinction will belong to NASA's Europa Clipper mission, which is scheduled to launch atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket in October 2024 and arrive at Jupiter in April 2030.

Clipper will remain in orbit around the gas giant, studying Europa during dozens of close flybys. These observations will reveal the thickness of the moon's ice shell and shed light on the subsurface ocean's life-hosting potential, NASA officials have said.

Europa Clipper will also serve as a scout, hunting for safe touchdown spots for another spacecraft — a lander that would look for signs of life on and just under Europa's icy surface. The Europa lander remains a concept at the moment; it is not officially on NASA's docket yet.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.