Hot 'Salsa:' European satellite burns up in landmark controlled reentry (photo)

Salsa was one of four Cluster satellites that had monitored Earth's magnetic field since 2000.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) Salsa satellite safely deorbited on Sunday (Sept. 8) over a hand-picked region of the South Pacific Ocean, in a carefully guided reentry that agency officials have applauded as the world's first.

Salsa was one of a quartet of identical satellites called Cluster, which launched in 2000 to monitor Earth's magnetic field and its interaction with the solar wind in an effort to advance space weather predictions. After nearly a quarter-century circling Earth over its poles — a vantage point that allowed Salsa to study hard-to-access parts of our planet's magnetic field — the prolific satellite was the first among its group to meet a fiery end following a successful atmospheric reentry at 2:47 p.m. ET (1847 GMT) on Sunday.

ESA predicted that most of the 1,200-pound (550 kilogram) satellite would burn up 50 miles (80 kilometers) above Earth's surface. The targeted reentry point over the sparsely populated South Pacific Ocean west of Chile guaranteed that any surviving parts would plunge in the open ocean, the agency previously said.

Such planned reentries of satellites at the end of their lives require operators to maneuver assets toward a predetermined region, an effort that scientists say could help minimize junk both in Earth orbit and in potentially populated regions on the surface.

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the space debris problem

"Salsa's reentry was always going to be very low-risk, but we wanted to push the boundaries and reduce the threat even further, demonstrating our commitment to ESA's Zero Debris approach," Rolf Densing, director of operations at ESA, said in a statement.

In preparation for Salsa's planned death dive, mission operators lowered the satellite's orbit in January via a series of four maneuvers that placed it over the South Pacific Ocean. The timing of those maneuvers was crucial to a smooth reentry, because Salsa swooped into Earth's shadow in February, where it stayed switched off and unable to rely on its power-generating solar panels for the next few months, ESA said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the days leading up to Sunday, operators watched closely as Salsa neared Earth, and adjusted its trajectory once to keep it on track for its reentry point, ESA said in the statement. From the amount of atmospheric drag the satellite was experiencing, teams at the agency's mission control in Germany correctly predicted its reentry at precisely 2:47 p.m. ET (1847 GMT), narrowing the previous uncertainty from about 1.5 hours to just under four seconds.

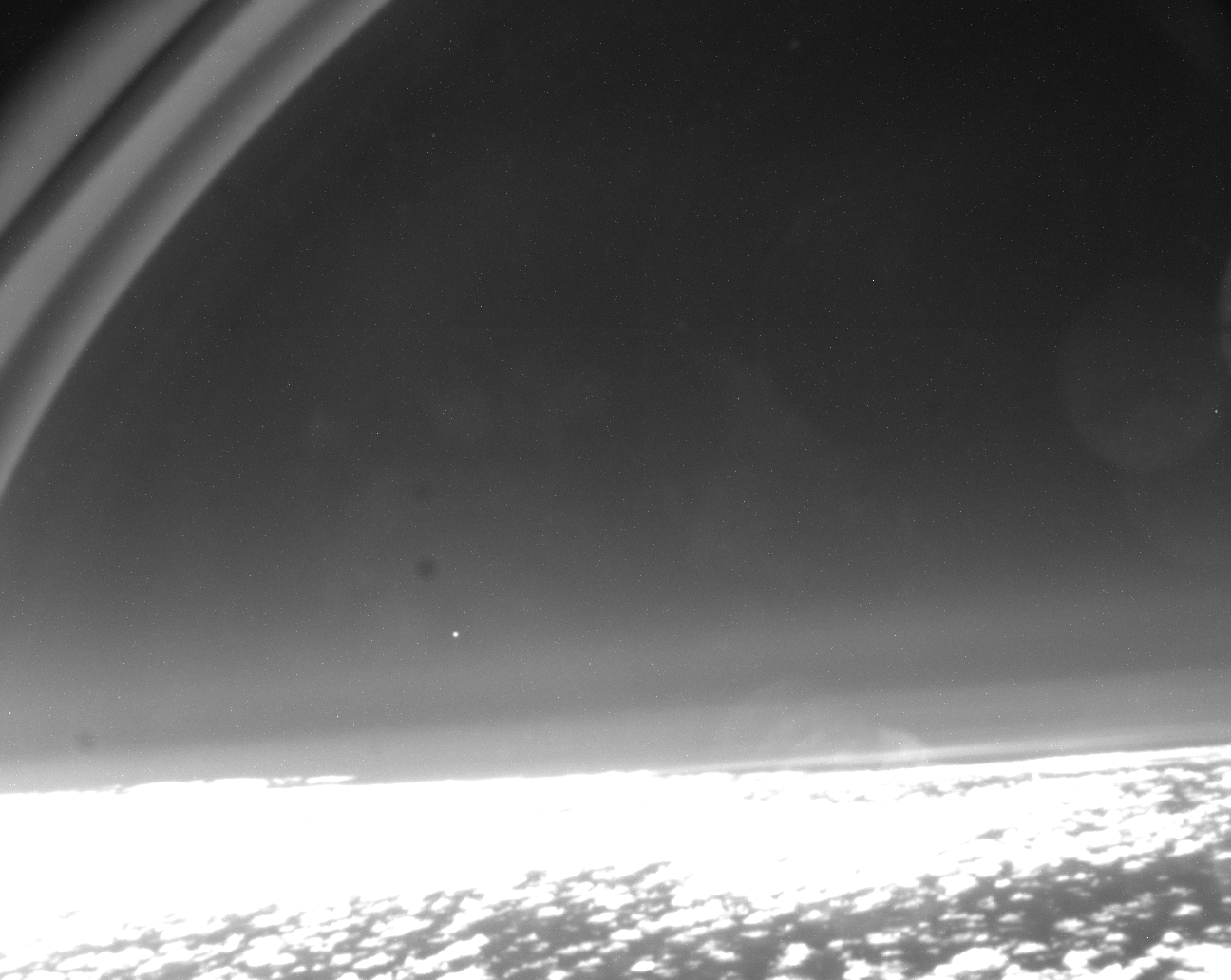

An aircraft that ESA flew out of Easter Island recorded Salsa's descent live, capturing the satellite as a speck of light in bright daylight.

The plane was equipped with 16 instruments to monitor the reentry and gather data about "what's happening on this reentry, how the satellite burns, what is burning at which moment and which altitude," all of which could inform satellite breakup models, Benjamin Bastida-Virgili, a space debris systems engineer at ESA, said in a Sept. 6 briefing, SpaceNews reported.

Those models will further benefit when Salsa's three counterparts — Rumba, Tango and Samba — perform targeted reentries between October 2025 and August 2026. All three satellites are now in what ESA calls a "caretaker mode;" their movement in orbit remains in the agency's control, but they are not carrying out any new science.

"By studying how and when Salsa and the other three Cluster satellites burn up in the atmosphere, we are learning a great deal about reentry science, hopefully allowing us to apply the same approach to other satellites when they come to the end of their lives," Densing said in the statement.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.