Space is becoming an 'unsustainable environment in the long term,' ESA says

"Overall, the report is full of bad news that is good news."

Space, just beyond the reach of Earth's atmosphere, is kind of like a teenager's bedroom: Even when you try to clean it, it somehow keeps getting messier.

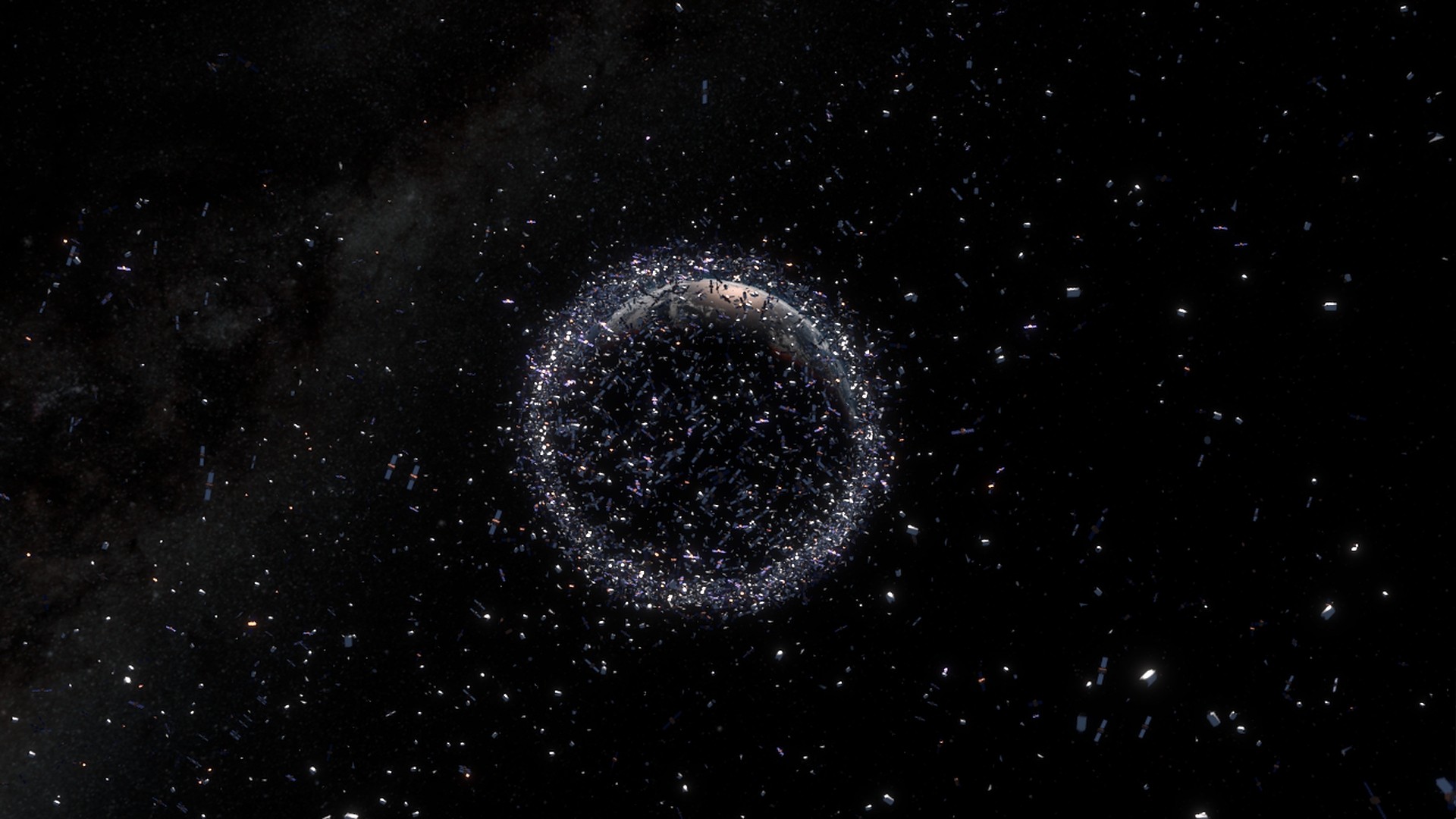

At least, that's one of the findings from the 2024 Space Environment Report published by the European Space Agency (ESA) on July 23. The report offers an accounting of satellites and debris accumulating in Earth's orbit. ESA's latest report, which has been published annually since 2017, is like a census for space activities and shows how bad the problem is becoming. According to its data, there are more than 35,000 objects being tracked by surveillance networks, with approximately 26,000 being pieces of debris larger than 4 inches in size.

The report suggests that despite an improved effort to mitigate this massive amount of space debris, the junk has continued to pile up. So much so, in fact, that we are creating "an unsustainable environment in the long-term," the report says.

Just this week, SpaceX revealed the 6,200 satellites in its Starlink megaconstellation have had to make almost 50,000 collision-avoidance manuevers over the past year, dodging junk and debris in low-Earth orbit. The company also had an on-Earth near-miss in May, after debris from one of its Crew Dragon spacecraft landed throughout the mountains of North Carolina, including on private residences.

ESA's report also details how humanity is launching more satellites than ever into space, driven by the uptick in commercial satellite endeavors, like SpaceX's Starlink. Of all the world's active satellites, ESA says that more than 6,000 find a home in low-Earth orbit at an altitude of between 310 and 370 miles (between 500 and 600 kilometers).

This region is like the cluttered freeway of Earth's orbit and ESA notes it's only going to get worse: Most satellites launched in 2023 were headed for those altitudes too. If debris were to collide with or explode on these busy space freeways, it could be catastrophic, kickstarting a chain reaction that dooms satellites and puts critical infrastructure like space-telescopes at low orbit space stations in harm's way. Effectively, it would shut down these freeways.

It sounds grim, but there are some positive signs. The report also states there have been increased efforts to mitigate space debris by deorbiting payloads and spent rocket bodies.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Space debris could be dealt with more cheaply than previously thought, new NASA report suggests

There was a huge increase in payload re-entries in 2023. More than 600 objects came tumbling back to Earth in an uncontrolled manner. One of the reasons is the increased solar activity, which is likely to see these uncontrolled re-entries occur at a much higher rate.

"The same thing that caused all those beautiful auroras in recent months will make the upper atmosphere swell and the resulting drag to bring LEO objects down in altitude much faster than normal," Mars Buttfield-Addison, a PhD researcher at the University of Tasmania and Australia's CSIRO working on ways to track satellites and space junk, told Space.com.

Even with improvements in mitigation efforts, there has still been a lack of compliance, with many larger payloads at the end of their mission not successfully removing themselves from orbit. That's junk that won't be coming down any time soon.

ESA predicts, based on extrapolating current trends, that the number of catastrophic collisions will begin to rise significantly – though this prediction is for the next few centuries, out to 2225, with smaller rises coming over the next few decades.

What the report makes clear is that implementation of mitigation measures remain "at a too low level to ensure a sustainable environment in the long run" and that some of the wins seen here are linked with the retirement of large constellations. In short, we should expect to see more junk in the near-term, unless we double down on strategies to curb the threat.

"Overall, the report is full of bad news that is good news," says Buttfield-Addison. "In many ways we are doing the best we can – lots of very clever and motivated people are working on mitigation by various means but they've long been hampered by physics, commercial interests, and international law."

Jackson Ryan is a science journalist hailing from Adelaide, Australia, with a focus on longform and narrative non-fiction work. He currently serves as the President of the Science Journalists Association of Australia. Between 2018 and 2023, he was the science editor at CNET. In 2022, he won the Eureka Prize for Science Journalism, which Aussies dub the "Science Oscars." Before all that, he got his doctorate in molecular biology and once hosted a kids TV show on the Disney Channel, called "GameFest." (Good luck finding it.) He lives with a collection of more than 70 Christmas sweaters and zero pets, the latter of which he hopes to rectify one day.