A newfound alien world may force scientists to rethink some of their ideas about planet formation.

An exoplanet 11 times more massive than Jupiter resides in b Centauri, a young binary star system about 325 light-years from Earth, a new study reports.

The planet, known as b Centauri b, is among the heaviest ever found. And combined, the two stars in b Centauri are six to 10 times heftier than our sun, making the system by far the most massive in which a planet has been discovered to date. b Centauri is also the hottest known planet-hosting star system, researchers said.

"Finding a planet around b Centauri was very exciting, since it completely changes the picture about massive stars as planet hosts," study lead author Markus Janson, an astronomer at Stockholm University in Sweden, said in a statement.

Related: The strangest alien planets (gallery)

A massive and hot star system

The two b Centauri stars are about 15 million years old — young pups compared to our sun, which has been burning for more than 4.5 billion years.

The duo's combined mass would seemingly make them unlikely planet hosts. After all, the heftiest known planet-harboring binary star system contains 2.7 solar masses, and the heaviest single stars confirmed to have worlds orbiting them are about three times more massive than our sun, study team members said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The b Centauri system's heat and power bolsters that bad-parent assumption. The main star, b Centauri A, is a B-type star with an estimated temperature around 32,000 degrees Fahrenheit (18,000 degrees Celsius), researchers said. That's about three times hotter than our G-type sun, and hotter than any other known planet-hosting star.

b Centauri B is therefore blasting out lots of high-energy X-ray and ultraviolet radiation, which tends to disperse planet-forming dust and gas.

"B-type stars are generally considered as quite destructive and dangerous environments," Janson said. "It was believed that it should be exceedingly difficult to form large planets around them."

Star facts: The basics of star names and evolution

Bucking the odds

The newfound planet bucked those odds.

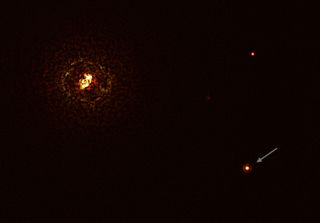

Janson and his colleagues discovered b Centauri b using the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research (SPHERE) instrument, which is installed on the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope in Chile.

SPHERE took a direct image of b Centauri b, a feat the instrument has pulled off with several other exoplanets. Analysis of the SPHERE observations allowed the researchers to characterize the planet, which has other extraordinary characteristics beyond its enormous size and the mass and heat of its parent stars. (The study team's research also revealed that ESO's 3.6-meter telescope in Chile managed to image the newfound planet more than 20 years ago, though nobody realized that at the time.)

For example, b Centauri b currently lies about 550 astronomical units (AU) from the star duo — about 14 times farther away than Pluto's average distance from the sun. (One AU is the average Earth-sun distance: about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers).

That's one of the widest planetary orbits known, said the authors of the study, which was published online Wednesday (Dec. 8) in the journal Nature. This immense distance may explain the planet's survival, keeping it at a relatively safe remove from the radiation blasting from the core of the b Centauri system.

b Centauri b's origin story is unclear at the moment. It may have formed relatively close to the binary star via "core accretion" — the most common planet-forming process, in which dust grains in a protoplanetary disk glom together to form rocky building blocks, whose mutual gravitational attraction eventually brings them together into planets. The young world could then have been booted to its present location by gravitational interactions, study team members said.

It's also possible that b Centauri b was born close to its current position, where core accretion is less viable, given the lower density of material out there. A far-flung formation, if it did indeed occur, may therefore have involved a different method known as "gravitational instability."

"This top-down model requires that the mass of the protoplanetary disk be so large that it causes part of the disk to collapse in on itself under the pull of its own gravity. When this happens, a small secondary body is created and starts to orbit the star," Kaitlin Kratter, of the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, wrote in an accompanying "News and Views" piece in the same issue of Nature.

"The gravitational-instability mechanism also tends to create objects that are very large — so large, in fact, that they fail to become planets," added Kratter, who is not a member of the study team. "Compared with the stars it orbits, this planet is small, making gravitational instability less likely than core accretion. Perhaps it is just a planet similar to Jupiter, flung out to the far reaches of its stellar system through an interaction with the stars it orbits. A broad census of planets associated with large stars will help to clarify the exact mechanism of its formation."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.