The nearest solar system to our own may actually host two potentially life-supporting planets, a new study reports.

In 2016, scientists discovered a roughly Earth-size world circling Proxima Centauri, part of the three-star Alpha Centauri system, which lies about 4.37 light-years from Earth. The planet, known as Proxima b, orbits in the "habitable zone," the range of distances from a star at which liquid water could exist on a world's surface. (A second planet, Proxima c, was later discovered circling the star as well, but it orbits farther away, beyond the habitable zone's outer limits.)

There's considerable debate about the true habitability of Proxima b, however, given that its parent star is a red dwarf. These stars, the most common in the Milky Way, are small and dim, so their habitable zones lie very close in — so close, in fact, that planets residing there tend to be tidally locked, always showing the same face to their host stars, just as the moon always shows Earth its near side. In addition, red dwarfs are prolific flarers, especially when they're young, so it's unclear if their habitable-zone worlds can hold onto their atmospheres for long.

Proxima b: Closest Earth-like planet discovery in pictures

Space.com Collection: $26.99 at Magazines Direct

Get ready to explore the wonders of our incredible universe! The "Space.com Collection" is packed with amazing astronomy, incredible discoveries and the latest missions from space agencies around the world. From distant galaxies to the planets, moons and asteroids of our own solar system, you’ll discover a wealth of facts about the cosmos, and learn about the new technologies, telescopes and rockets in development that will reveal even more of its secrets.

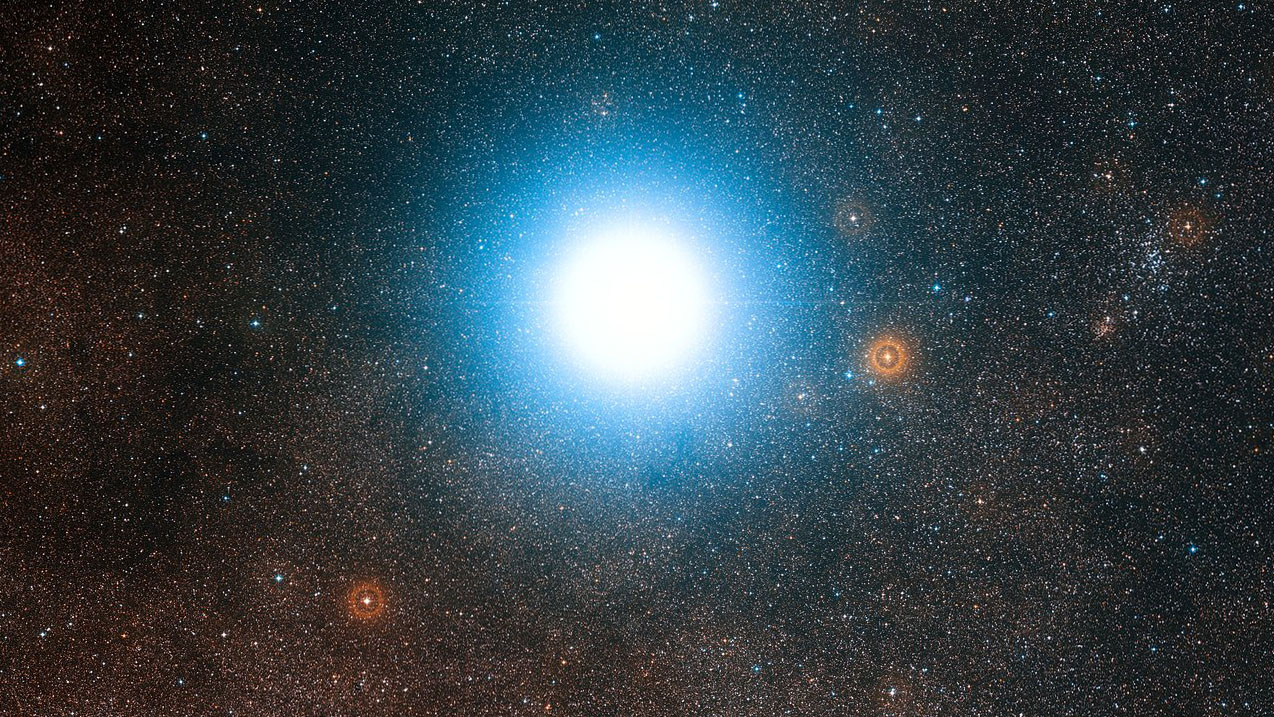

The other two stars in the Alpha Centauri trio, however, are sunlike — a pair called Alpha Centauri A and B, which together make up a binary orbiting the same center of mass. And Alpha Centauri A may have its own habitable-zone planet, according to the new research, which was published online today (Feb. 10) in the journal Nature Communications.

The study presents results from Near Earths in the Alpha Cen Region (NEAR), a $3 million project led by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and Breakthrough Watch, a program that hunts for potentially Earth-like worlds around nearby stars.

NEAR has been searching for planets in the habitable zones of Alpha Cen A and B using ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. The NEAR team upgraded the VLT with several new technologies, including a thermal coronagraph, an instrument designed to block a star's light and allow the heat signatures of orbiting planets to be spotted.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After analyzing 100 hours of data gathered by NEAR in May and June of 2019, the scientists detected a thermal fingerprint in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri A. The signal potentially corresponds to a roughly Neptune-size world orbiting between 1 and 2 astronomical units (AU) from the star, study team members said. (One AU, the average Earth-sun distance, is about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

But that planet has not yet been confirmed, so it remains a candidate for now.

"We were amazed to find a signal in our data. While the detection meets every criteria for what a planet would look like, alternative explanations — such as dust orbiting within in the habitable zone or simply an instrumental artifact of unknown origin — have to be ruled out," study lead author Kevin Wagner, a Sagan Fellow in NASA's Hubble Fellowship Program at the University of Arizona, said in a statement.

"Verification might take some time and will require the involvement and ingenuity of the larger scientific community," Wagner added.

Study co-author Pete Klupar said he hopes the new results will inspire astronomers to study the Alpha Centauri system in greater detail, both via new observing programs and closer scrutiny of archived data, which may hold as-yet unrecognized evidence of the exoplanet candidate.

"It's like getting a hint in [the board game] Clue," Klupar, a researcher with Breakthrough Watch's parent organization, Breakthrough Initiatives, told Space.com. "Now that we've got the hint, maybe they can find something."

And, if the Alpha Centauri A world does indeed exist, it may not be alone.

"In my mind, the most exciting thing about this is, once we find one planet, we tend to find others," Klupar said.

Even if the Alpha Cen A planet turns out to be a mirage, however, NEAR's work will not have been in vain, team members said.

"The new capability that we demonstrated with NEAR to directly image nearby habitable-zone planets is inspiring to further developments of exoplanet science and astrobiology," Wagner said in the same statement.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.