'Eyeball Earth' Alien Planets May Be Lifeless 'Snowballs'

Alien worlds resembling giant eyeballs might be able to host life, but they may not be as common as previously suggested, a new study finds.

Instead, the oceans that would make such planets resemble humongous eyeballs might often get clouded or covered entirely by sea ice, messing up their eyeball-like appearance and potentially reducing their chances of being habitable to life as we know it, researchers said.

These alien worlds are thought to exist around red dwarfs, the most common type of star in the universe. These stars are small and cold, about one-fifth as massive as the sun and up to 50 times dimmer. They account for up to 70% of all the stars in the universe, a huge number that potentially makes them valuable places to look for extraterrestrial life. Indeed, NASA's Kepler space telescope found that at least half of these stars host rocky planets that are half to four times the mass of Earth.

Related: The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)

Research into whether an exoplanet might host life as we know it usually focuses on whether or not it has liquid water, since there is life virtually wherever there is liquid water on Earth. Scientists typically concentrate on the habitable zones of stars, also known as Goldilocks zones — the area around a star temperate enough for a world to possess liquid water on its surface.

One study in 2014 suggested that nearly every red dwarf may have a planet in its habitable zone. This work also suggested that such worlds could each possess about 25 times more water than Earth has as a whole.

The habitable zones around red dwarfs are close to these stars because of how dim they are, often closer than the distance Mercury orbits the sun. This closeness makes them appealing to hunters of alien planets, since worlds near their stars cross in front of them more often from our perspective, making them easier to detect than planets that orbit farther away from their stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

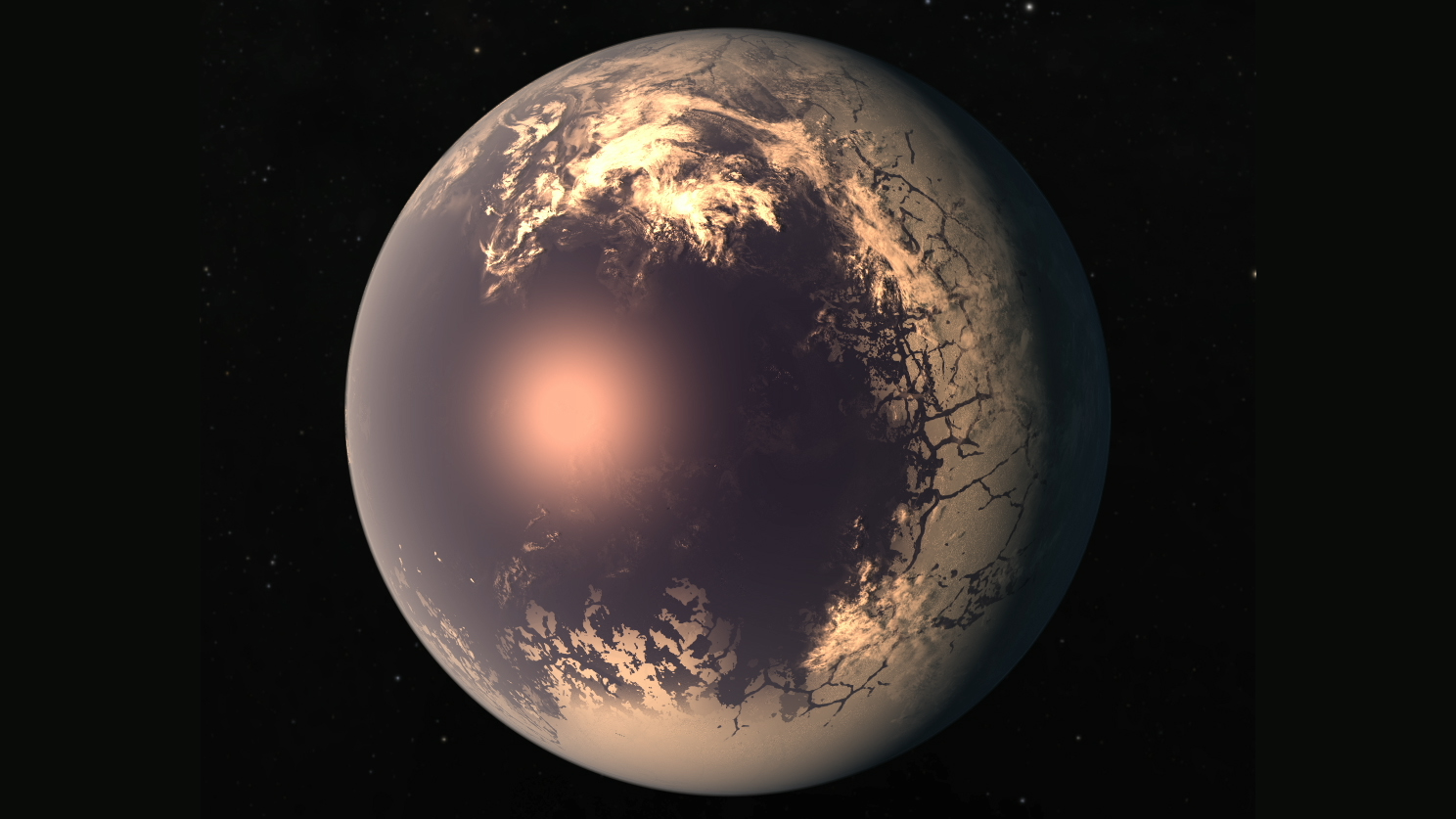

When a planet orbits a star very closely, the star's gravitational pull can force the world to become "tidally locked" with it, meaning the planet will always show the same face to its star just as the moon does to Earth. This scenario of planets each with one permanent dayside and one permanent nightside could lead to a striking kind of world — one resembling an eyeball. Its nightside would be covered in a frozen, icy shell, while its dayside would host a giant ocean of liquid water constantly basking in the warmth of its star.

However, previous research into how tidally locked exoplanets around red dwarfs might look did not account for how sea ice might influence the flow of heat and cold within the oceans of such worlds. Sea ice would drift around these oceans because of the strong winds that would result from air heated on each world's dayside rushing to its cooler nightside. As this sea ice melted, it would absorb heat from the water and the overlying atmosphere.

Now, scientists in China find that drifting sea ice might often cool such exoplanets enough to prevent them from becoming eyeball worlds. Instead, many such exoplanets might become "snowballs" clad completely in ice.

Previous research suggested that Earth may have itself experienced snowball states a number of times in its history — "one is about 2.2 billion years ago, and the other one is about 630 million years ago," Jun Yang, a climate scientist at Peking University in Beijing and the lead author of this new study, told Space.com. "During these snowball states, all the oceans' surfaces were covered by sea ice and snow, and maybe nearly all the continents were covered by thick ice sheets."

Yang and his research team developed 3D computer simulations modeling how ice that forms near the edges of an eyeball planet's ocean can drift and melt. This sea ice essentially transported cold from each world's nightside to its dayside.

The scientists also modeled the climate of these exoplanets, including the effects of greenhouses gases such as carbon dioxide, which warm planets by trapping heat from their stars. They found that when these worlds did not possess much more greenhouses gases than Earth, their dayside oceans can shrink and even disappear, converting them into snowballs.

The researchers found this snowball effect could happen even when exoplanets in a red dwarf's habitable zone were not tidally locked into permanent daysides and nightsides, but slowly changed which face they presented their stars, as Mercury does with the sun.

"Some planets that were thought to be habitable may be not really habitable," Yang said. "They may [be] in an extremely cold snowball state, in which no sunlight could reach the liquid water. Sunlight is necessary for all types of photosynthetic organisms."

Still, the scientists found not all exoplanets in a red dwarf's habitable zone would become snowballs. "For example, if a planet has a very high level of greenhouse gas such as carbon dioxide or methane, it will not fall into a snowball state because of the strong greenhouse effect," Yang said.

Furthermore, just because a planet is a snowball does not mean it is completely uninhabitable, as Earth's prior snowball states revealed. For instance, photosynthetic organisms could in theory dwell in regions with thin ice where starlight could penetrate, or in volcanically heated areas free of ice, Yang said.

In addition, when it comes to planets in the inner edges of a red dwarf's habitable zone, the amount of light they receive "is high enough to melt the ice and snow at the surface and maintain liquid water on the dayside and even on the nightside," Yang said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 23 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

- 'Snowball' Planets Might Be Better Abodes for Life Than We Thought

- Brrr! Earth-Like Alien Planets Could Experience 'Snowball States'

- Water Vapor Detected in Atmosphere of an Alien World Nearly Twice the Size of Earth

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us