The 'faintest asteroid ever detected' won't hit Earth, months of observations show

"These would turn out to be some of the trickiest asteroid observations we have ever made."

An asteroid discovered in August 2021 seemed on a collision course with Earth, but an extensive observation campaign that involved one of the world's most powerful telescopes eventually ruled out the space rock as a risk.

The asteroid, dubbed 2021 QM1, gave astronomers quite a headache. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), it was at one point "the riskiest asteroid known to humankind," as it appeared bound to slam into our planet in April 2052 even after multiple observations and recalculations of its orbit.

It took the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile, one of the most powerful optical telescopes in the world, to eventually rule out the collision. The telescope had to track the 160-feet-wide (50 meters) space rock as it moved so far away from Earth that it eventually became "the faintest asteroid ever observed," according to ESA.

Related: NASA's DART mission will move an asteroid and change our relationship with the solar system

Multiple telescopes observed 2021 QM1 shortly after it was discovered by Mount Lemmon observatory in Tucson, Arizona. Initially, with every new observation, it seemed more and more certain that the asteroid might come "dangerously close" to Earth in three decades. An asteroid 160 feet wide would cause damage equivalent to the nuclear bomb dropped by the U.S. on Hiroshima at the end of World War II, so scientists were concerned about the calculations.

"These early observations gave us more information about the asteroid's path, which we then projected into the future," Richard Moissl, ESA's head of planetary defense, said in a statement. "We could see its future paths around the sun, and in 2052 it could come dangerously close to Earth. The more the asteroid was observed, the greater that risk became."

With the predicted collision risk uncomfortably high, the asteroid disappeared for several months in the glare of the sun as its orbit brought it closer to our star. Astronomers knew that by the time the space rock would reach darker skies again, it would be too far away and therefore too faint to be observed by most ground-based telescopes. They therefore solicited help from the Very Large Telescope, which, with its 26-foot-wide (8 m) mirror, had a reasonable chance of detecting the rock. Still, it was a daunting task.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

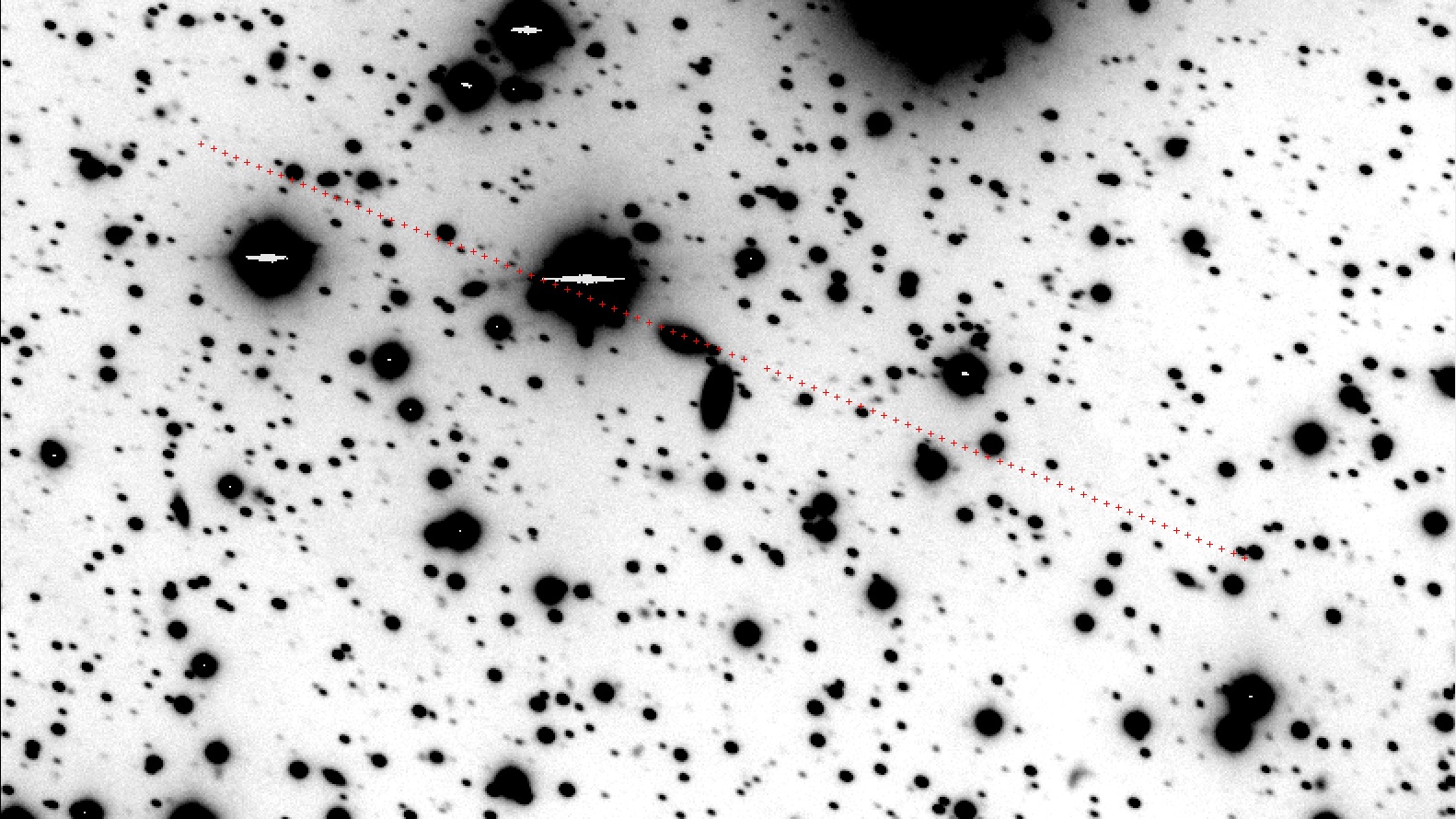

"We had a brief window in which to spot our risky asteroid," Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer at ESO, said in the statement. "To make matters worse, it was passing through a region of the sky with the Milky Way just behind. Our small, faint, receding asteroid would have to be found against a backdrop of thousands of stars. These would turn out to be some of the trickiest asteroid observations we have ever made."

The telescope managed to detect 2021 QM1 when the space rock had a magnitude of 27. For comparison, the magnitude of the sun, the brightest object in our sky, is minus 27. (The magnitude scale reverses the actual brightness of objects; the brightest stars in the sky have a magnitude around 0.)

The observation campaign provided enough data for the planetary defenders to refine the orbit of 2021 QM1 and rule out the 2052 collision.

More than 1 million asteroids have been discovered in the solar system since observations began, almost 30,000 of which pass near Earth. Astronomers have managed to track most of the very large rocks that could threaten the entire planet, but many of the smaller ones that could still cause significant damage, like 2021 QM1, remain unknown.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.