This Scientist Is Creating Fictional Asteroids to Save Humanity from Armageddon

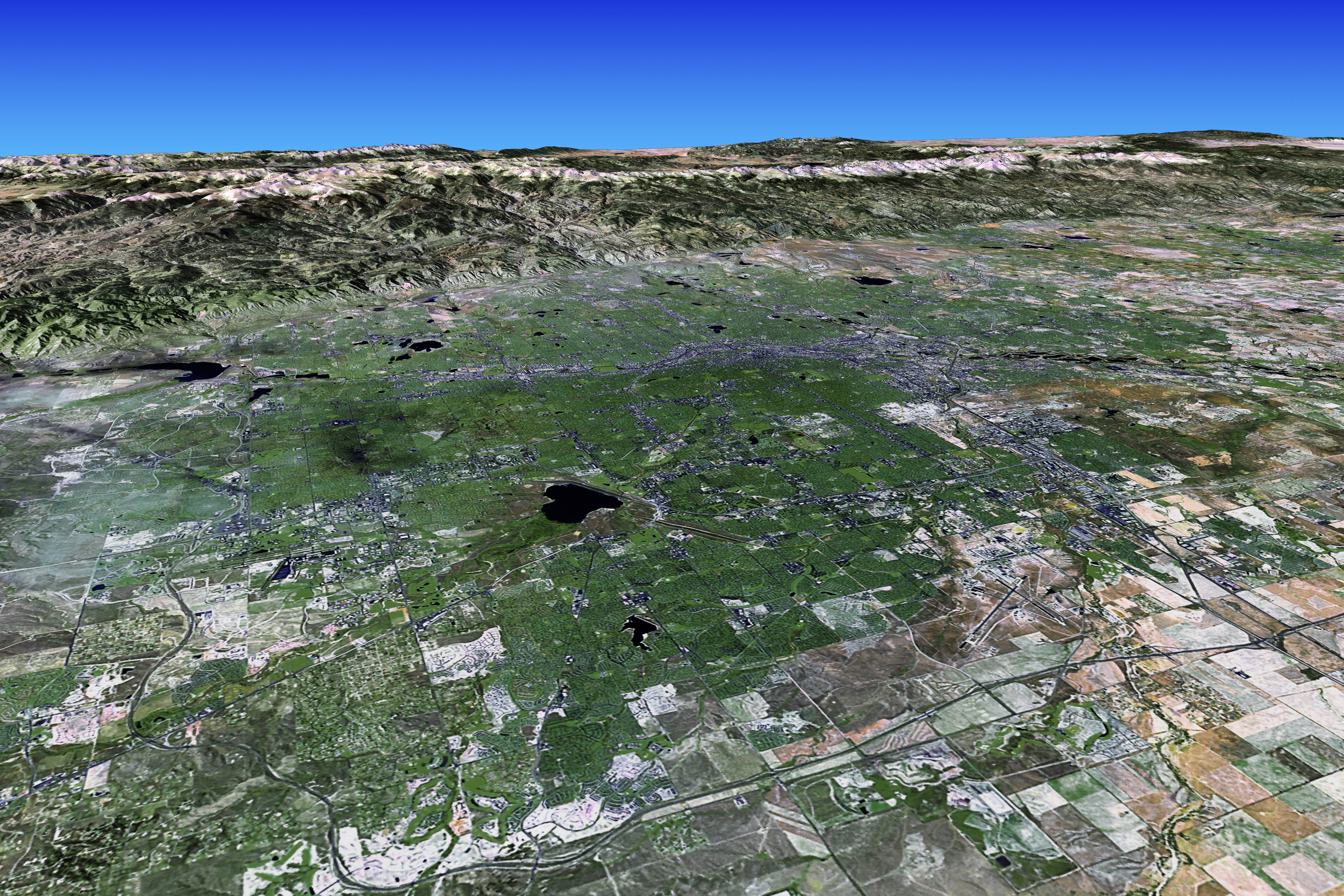

COLLEGE PARK, Md. — It's a nightmare scenario to imagine: a large asteroid headed directly for a major American city, Denver, less than eight years after astronomers spotted the space rock.

Fortunately, this asteroid, called 2019 PDC, is fictional. It's the brainchild of Paul Chodas, who specializes in modeling the trajectories of near-Earth objects at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, and his colleagues in an exercise scenario unfolding at the International Academy of Astronautics' Planetary Defense Conference being held here this week.

"The idea is to make a realistic simulation of an asteroid headed for the Earth and then study all of the things we would know and what we wouldn't know and how the story would develop," Chodas told Space.com. His task, which he began more than six months before the conference started, is to create all of the parameters of a nonexistent but realistic asteroid that will allow scientists, mission designers, emergency managers and other decision makers to think through what they would do if such a scenario were to unfold in real life.

Related: A Killer Asteroid Is Coming — (So Let's Be Ready), Bill Nye Says

Chodas is well suited for the task, given his real job at NASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies, which hosts a database of just over 20,000 asteroids with orbits that carry them near Earth, feeding observations into detailed models to predict their future paths and whether they pose a risk to humans. None of the known asteroids in the largest class — that is, those bigger than 460 feet (140 meters) across — pose such a danger for the foreseeable future.

But our luck may change. And that prospect worries planetary-defense experts, who focus on the risk that nearby asteroids pose to Earth. Hence the conference and the scenario exercise that is unfolding here now.

For each scenario Chodas develops, he starts with a given impact site — this time, Denver. Then, he develops an orbit that makes it plausible for astronomers to have missed the object after watching the skies for decades. "It's kind of orbit engineering on my part," Chodas said. "We work the whole story backwards from the location." But he does his best to keep the narrative interesting at each step of the process in order to build a robust story.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: How Do You Stop a Hypothetical Asteroid From Hitting Earth?

That means making sure the hypothetical orbit lets scientists spot the object soon enough that humans have time to respond, but not so early that it's a straightforward response. "The eight years is intentionally set as something that would press the schedule for mitigation, for deflection," Chodas said.

That priority also dictates where he sets the impact corridor — the swath along Earth that intersects with the hypothetical asteroid's orbit, where the two bodies could theoretically collide. When the hypothetical asteroid was originally "detected," it wasn't just Denver that could have fallen victim; Hawaii, the San Francisco Bay Area, New York City and a large swath of Africa were all at risk.

To construct the scenario, Chodas also had to decide what sorts of information he would dole out about the asteroid and when. Mass is incredibly difficult to measure accurately, so as the scenario plays out, would-be responders have to work from vague estimates instead. An initial flyby mission cobbled together soon after the first detection discovers that the hypothetical object is what scientists call a contact binary — two hunks of space rock that have fused together.

That's a key plot point for Chodas in this conference's scenario because, as usual, he opted to make things more complicated for those tackling the asteroid problem. In the hypothetical scenario, when spacecraft arrive to collide with the asteroid and slow it down, they accidentally break the space rock instead. As conference attendees learned yesterday (May 2), the larger piece turns out to be harmless, but the smaller chunk is headed toward Earth — and this time, scientists can't guess where it will fall along a swath stretching from Lincoln, Nebraska, to New York City, to the Atlantic Ocean.

"It's not just an orbit and it's done; we have to engage all the communities of planetary defense," Chodas said. "We generally like to study how deflection would work and all the challenges there."

Related: Huge Asteroid Apophis Flies By Earth on Friday the 13th in 2029

The conference attendees will get one more batch of challenges today before they have to walk through what they would do and why — and how it would play out for people on the ground. "Each day we seem to be making it more and more difficult … so we can stress the community and have them consider the worst-case scenario," Chodas said. "When you have population at risk, that really makes it a stressful decision perhaps, and makes it sobering."

Chodas has been designing hypothetical asteroids since the 1990s, and as the teams running the exercises have grown, the scenarios have become much more detailed and complicated. In turn, the planetary-defense community has recognized new complications — and this way, they've started thinking about these potential obstacles before real people become at risk.

So, sure, Chodas kind of flung an asteroid at Denver. But it isn't personal. "I have no mean intentions here," Chodas said. But an easy scenario won't do the job, and he doesn't shy away from throwing in an extra twist where he can. "I like to add color, because a story is not believable if there aren't bits of color around the edges."

- Humanity Will Slam a Spacecraft into an Asteroid in a Few Years to Help Save Us All

- Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space

- Wow! Asteroid Ryugu's Rubbly Surface Pops in Best-Ever Photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.