First close-up pictures of Mercury from BepiColombo hint at answers to the planet's secrets

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences, The Open University

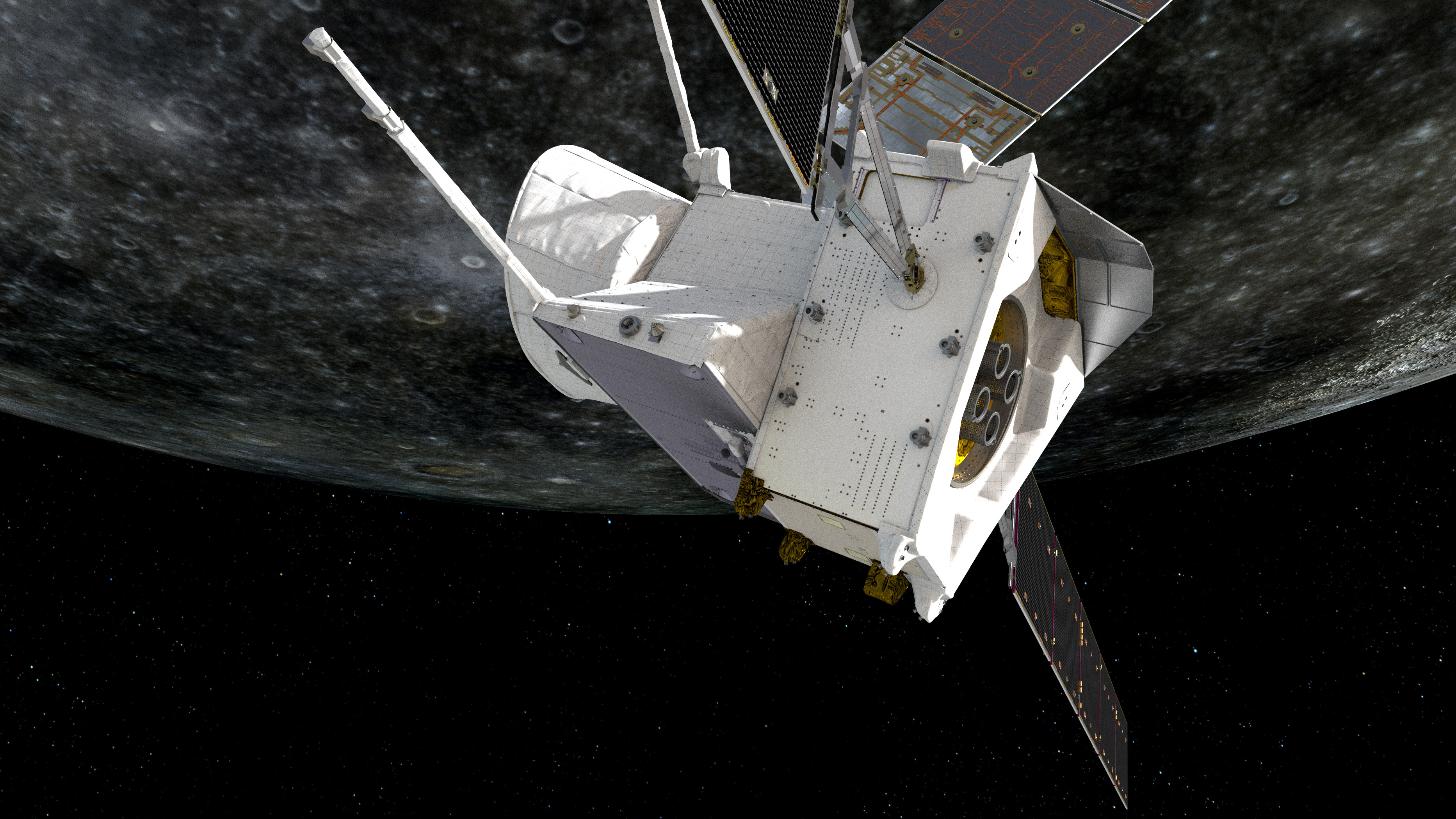

The BepiColombo spacecraft – a joint project by the European and Japanese space agencies – swung by its destination planet Mercury in the early hours of Saturday, Oct. 2. Passing within just 124 miles (200 kilometers) of the surface of Mercury, it sent back some spectacular pictures.

For those of us who have worked for a decade or more on this mission, there could hardly be a way better to celebrate what would have been the 101st birthday of the mission's namesake, Italian mathematician and engineer Giuseppe Colombo. His groundbreaking work in this area earned him the title of the grandfather of the planetary fly-by technique, now more often termed a "swing-by."

BepiColombo’s cruise from Earth began in October 2018, and its journey is far from over. It will travel twice around the sun in the time it takes Mercury to orbit the star three times (around 264 days). This will allow it to rendezvous with the planet for another swing-by on June 23 2022.

After a total of six Mercury swing-bys, the cumulative effect of the planet's gravity will reduce the spacecraft's velocity to the point where it can fall into orbit with Mercury around the end of 2025.

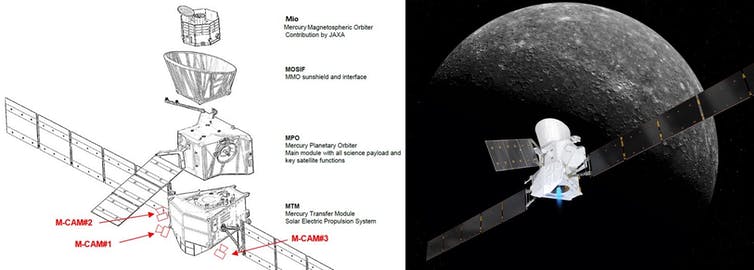

BepiColombo is actually composed of two connected spacecraft and a propulsion unit. During its cruise through interplanetary space, the European orbiter (called the Mercury Planetary Orbiter or MPO) is attached on one side to the interplanetary propulsion unit (or Mercury Transfer Module). On the other, it carries a Japanese orbiter named Mio (or Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter), plus a sunshield to prevent Mio from overheating.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This stacked configuration obstructs the openings through which sophisticated visible, infrared and X-ray cameras inside MPO – capable of imaging and analysing Mercury’s surface in great detail – will operate once MPO finally becomes free-flying. In fact, most of BepiColombo’s science instruments will be wholly or partly inoperative until each orbiter is set free, around December 2025.

Adding the cameras

Until a relatively late stage in mission planning, it was accepted that BepiColombo would be "flying blind" during its whole cruise from Earth, including during swing-bys – meaning no images would be available until orbit around Mercury had been achieved.

But the level of public interest aroused in 2015 by images of comet 67P from the Rosetta mission led BepiColombo engineers Kelly Geelen and James Windsor to propose that low-cost lightweight cameras should be added to the spacecraft.

By the end of 2016, it was agreed that three small monitoring cameras – each only 2.6 inches (6.5 centimeters) in length – would be mounted onto the craft. These would snap planetary pictures during swing-bys.

It was decided to place these cameras on the Mercury Transfer Module, where they would also be able to monitor the deployment of the solar panels that provide the spacecraft with power, the magnetometer boom used for measuring magnetic fields, and the communication antennas.

What Bepi saw

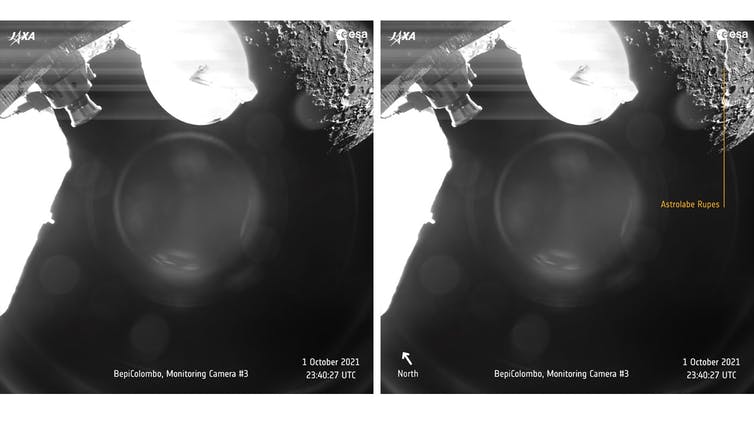

During BepiColombo's first Mercury swing-by, the fields of view of monitoring cameras two and three tracked across the planet. Camera three showed us part of the southern hemisphere, beginning with a view of sunrise over Astrolabe Rupes – a striking feature named after a French Antarctic exploration ship.

Astrolabe Rupes is a 155-mile (250 km) long "lobate scarp" – a long, curved structure marking where one part of the planet’s crust has been pushed over nearby terrain, due to the whole planet contracting as it slowly cooled.

There are some much smaller equivalent features on the moon, but Mercury is the only nearby celestial body where lobate scarps are known to occur on such a large scale.

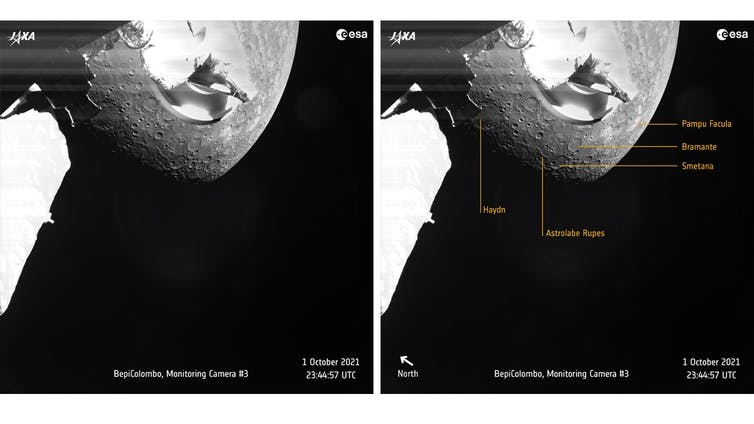

Four minutes later, the perspective had changed enough to reveal a wider area: including the lava-flooded, 156-mile-wide (251 km) Haydn crater and Pampu Facula, one of many bright spots likely formed by explosive volcanic eruptions. Both of these features attest to Mercury's long volcanic history, at its most active more than three billion years ago but probably persisting until around one billion years ago.

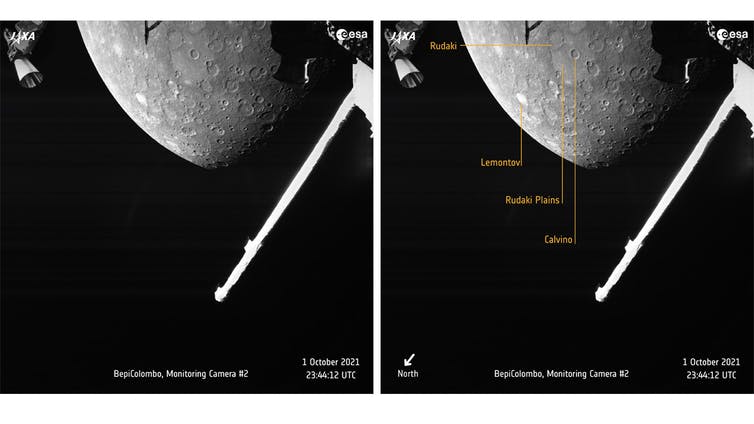

Meanwhile, camera two focused on Mercury's northern hemisphere, including the region surrounding Calvino Crater: an important location for deciphering what lies in the layers of Mercury’s crust.

It also showed Lermontov crater: a region which appears bright because it is host to both volcanic deposits and "hollows", where a currently unknown volatile ingredient of the crust is being lost to space via a mysterious process.

NASA's MESSENGER mission orbited Mercury between 2011 and 2015, revealing a perplexing planet. We are still struggling to understand its composition, origin and history.

Why Mercury has features such as explosive volcanoes and strange, unique hollows on its surface is just one of the problems we hope further study will solve. Once in orbit, BepiColombo's advanced payload of scientific instruments will help us understand more about how Mercury formed and what it’s made of.

Read more: The more we learn about Mercury, the weirder it seems

In the meantime, these extraordinary swing-by pictures at least remind us that we have a healthy spacecraft heading to an exciting destination.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

David Rothery is a professor of planetary geosciences at the Open University in Milton Keyes, England, where he studies volcanic activity with remote sensing, as well as volcanology and geoscience on other planets. He earned a Ph.D. on the applications of remote sensing from Open University in 1982 and has been a professor of planetary geosciences since 2013. Prior to that he had served as a senior lecturer since 1994. David is the U.K. lead co-investigator on the Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer aboard the European Space Agency's BepiColombo mission to Mercury and chairs ESA's Mercury Surface and Composition Working Group. He is the author of several books on space geosciences, including his landmark Planet Mercury: From Pale Pink Dot to Dynamic World (Springer-Praxis, 2014). You can see David's latest updates by following him on Twitter.