Around 3000 B.C., during the time of the ancient Persians in what today we would call Iran, there were four "royal stars" in the nighttime sky. Presumably, in accordance with Persian culture, the sky was divided into four districts with each district being guarded by one of these four special stars.

All four were first-magnitude stars — among the 21 brightest stars in the sky — which was apparently a prerequisite for being designated as "royal," or one of the symbolic, stellar guardians of the heavens.

Another apparent prerequisite, was that these stars needed to be close to the ecliptic, that imaginary line in the sky along which the sun, moon and five naked-eye planets appear to follow. That line also passes through the 12 constellations that compose the signs of the zodiac.

Related: Happy Equinox! It's the 1st Day of Autumn in Earth's Northern Hemisphere

Three of these stars met the proper requirements: the bright, orange star Aldebaran in the constellation Taurus (the bull), the bluish star Regulus in Leo (the lion), and the ruddy star Antares in Scorpius (the scorpion).

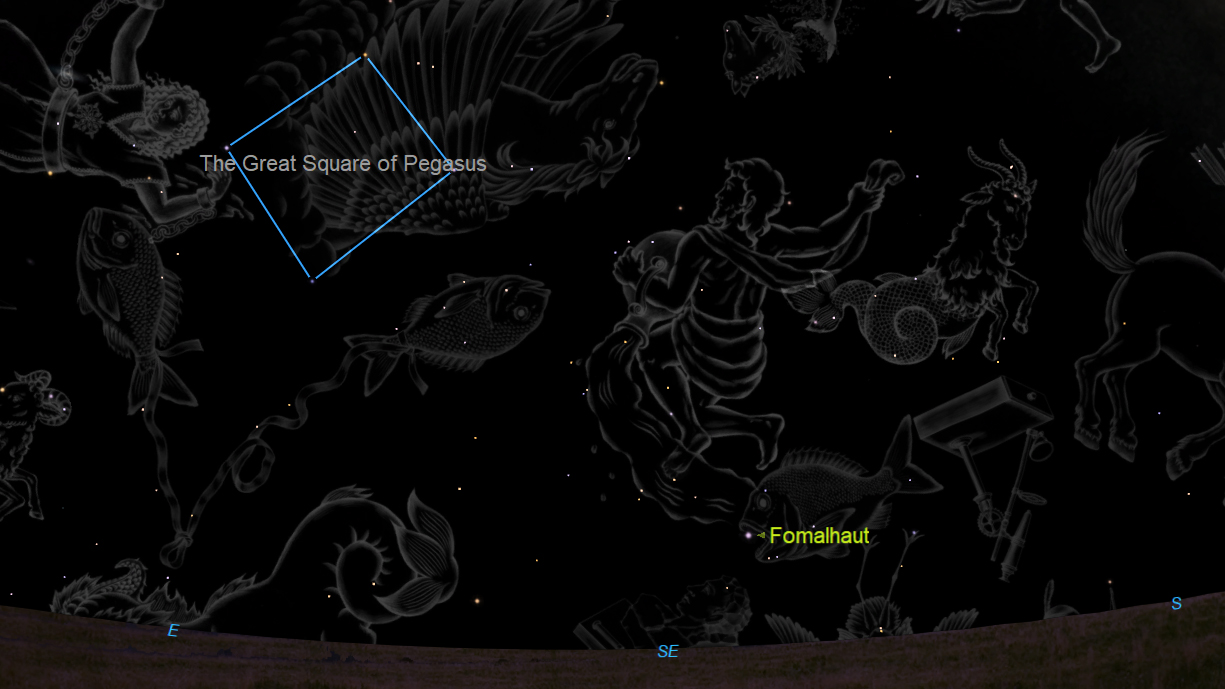

But for the fourth district, the one that encompasses our current evening sky for autumn, there was a problem in that there was no bright star present along the ecliptic. The most noteworthy zodiacal star patterns of autumn included Capricornus (the sea goat), Aquarius (the water carrier) and Pisces (the fishes). Indeed, this region of the sky is popularly known as the "celestial sea" and is a wide, dark area devoid of bright stars and composed of star patterns that all have an association with water. Capricornus, Aquarius and Pisces are three constellations that contain stars no brighter than third-magnitude ... and many more are actually in the much fainter fourth- and fifth-magnitude category.

So, in order to designate a fourth (bright) "royal star" candidate, the ancient Persians begrudgingly had to find a star that was not in the zodiac. They finally came up with Fomalhaut, the 18th-brightest star in the sky, in the modern constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the southern fish).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A stellar eremitic

Sometimes referred to simply as "The Solitary One," Fomalhaut stands out in what is otherwise a rather empty region of the autumn sky. In her 1907 book, "The Friendly Stars," Martha E. Martin wrote:

"On early acquaintance, the loneliness of this star, added to the somber signs of approaching autumn, sometimes giving one a touch of melancholy."

With these words, Fomalhaut certainly can be considered to be the star that announces the arrival of fall.

For those living at mi-northern latitudes, such as New York, Chicago and Denver, it is the southernmost of the visible first-magnitude stars, never climbing more than about 20 degrees above the southern horizon at its highest. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures 10 degrees, so Fomalhaut, at best, gets only about "two fists" above the horizon.

To make a positive identification, this week around 9:30 p.m. local time, look high in the southeast sky for one of the landmarks of autumn: the Great Square of Pegasus. Trace an imaginary line along the western (right hand) side of the Square and extend that line about 3.5 times that distance, and there you will find Fomalhaut. There are no bright stars along the way; you'll be passing through the dim regions of Pisces and Aquarius. In fact, the water pouring from the water jar that is held by Aquarius consists of some ill-defined lines of stars stretching south. And it is near the end of one of these lines that we come to Fomalhaut.

Piscis Austrinus was often pictured in many old star atlases as a long, slim fish with an open mouth and is usually depicted drinking the water that flows from the water jar of Aquarius.

This would make some sense, since Fomalhaut is really a corruption of the Arabic "Fum al Hut," meaning "mouth of the fish." Some believe that Fomalhaut symbolizes the New Testament story of St. Peter and a coin (a tetradrachm) found in the mouth of a fish.

Fomalhaut is situated 25 light-years away from Earth — close by stellar standards — and is nearly twice as large and as massive as our sun. It is also nearly 17 times more luminous and shines with a white color, although more than a few constellation guidebooks refer to it as appearing with a reddish hue. This is probably because it appears rather low in the sky, that the haze that often lurks near the horizon attenuates its light and tends to give it a somewhat ochre hue.

Fun facts about Fomalhaut

Three other things make Fomalhaut a most interesting star.

First, Fomalhaut is relatively quite young, only about 440 million years old. In contrast, our sun is estimated to be about 5 billion years old. Because Fomalhaut is hotter and brighter than our sun, it also has a shorter life span of somewhere around 1 billion years. Stars like the sun have life spans of about 10 billion years.

Second, is that Fomalhaut is surrounded by several regions of dense gas and dust, which astronomers refer to as a protoplanetary disk. Near the outer edge of this disk, in November 2008, the Hubble Space Telescope captured an image of an object believed to be an extrasolar planet orbiting Fomalhaut. The planet in question is estimated to be about three times as large as Jupiter, yet only as massive as Neptune. Some believe that this might not be a planet at all, but merely a gravitationally bound accumulation of rubble.

Third, there is a faint (magnitude +6.5) dwarf star, known as TW Piscis Austrini, located about 2 degrees to the south, that appears to be sharing Fomalhaut's motion through space. This star shines with less than 20% of the luminosity of our sun, but is so distant — nearly 1 light-year from Fomalhaut — that it's difficult to call them a binary star system. Some speculate that these two stars are the sole remnants of a low-density star cluster that dissipated long ago.

Believe it or not, an extrasolar planet might also be circling TW Piscis Austrini. NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), a space telescope that's searching for planets around the brightest stars in Earth's night sky, recently found a possible candidate circling this star. It's almost the same size as our Earth, and orbits the star about every 10 days at a distance of 7.5 million miles from it. However, more observations are needed to confirm whether the exoplanet really exists.

Finally, aside from Fomalhaut, the stars that make up the rest of the southern fish are — no surprise — dim and hard to see. Perhaps this makes Piscis Austrinus a shy fish.

That, or he's very koi.

- The Stars of Autumn's Night Sky: What to Look For

- Why the Night Sky Changes With the Seasons

- How Bright Are the Stars Really?

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.