Full Hunter's Moon puts on a spooky display today with partial lunar eclipse

October's full moon and partial lunar eclipse will give the weekend before Halloween the perfect spooky aesthetic for trick-or-treaters.

Editor's note: The partial lunar eclipse of 2023 is over but you can see amazing video of its peak here. Read our wrap story for more stunning lunar eclipse photos.

The moon will put on a spectacularly spooky show for trick-or-treaters this weekend as the full Hunter's Moon experiences a partial lunar eclipse.

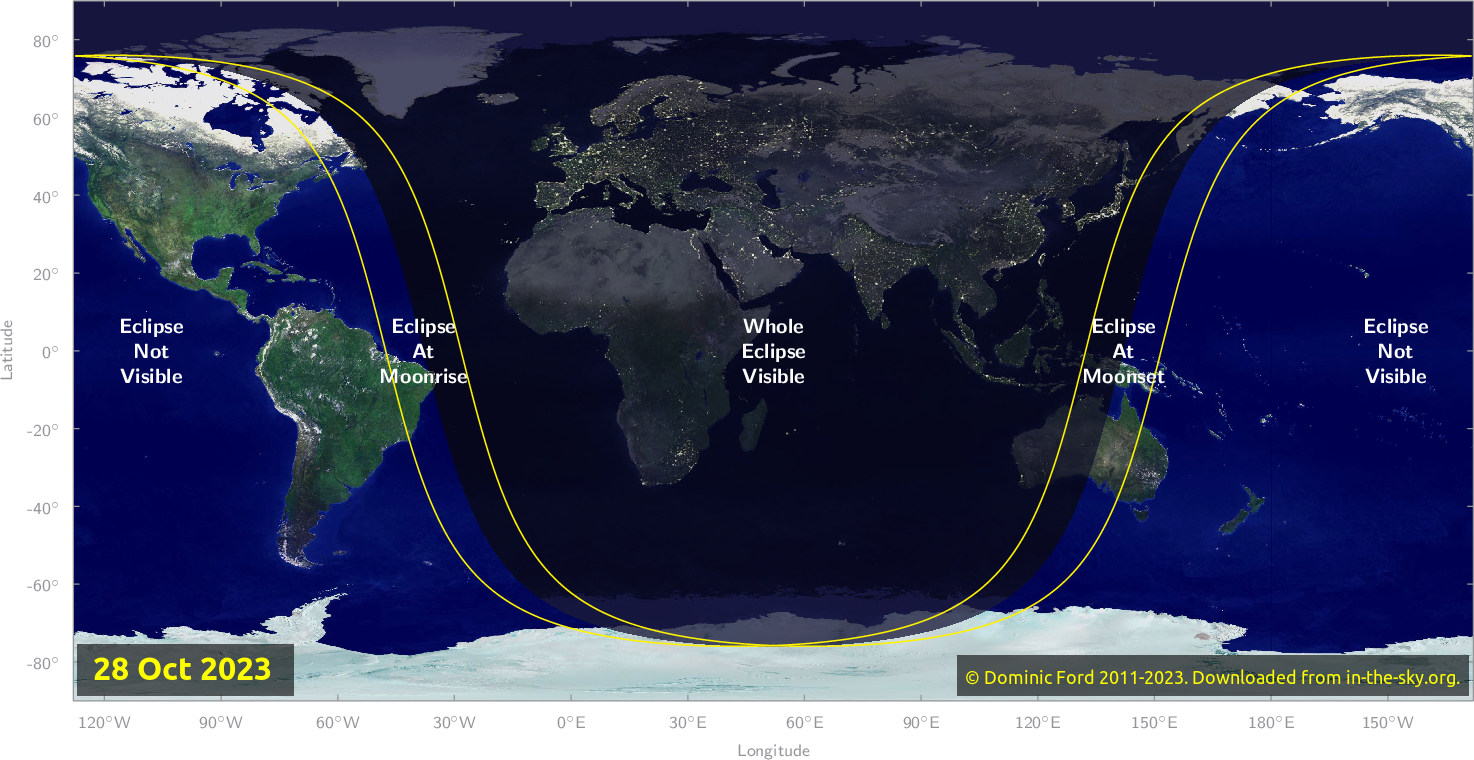

The partial lunar eclipse will be visible to observers in Africa, Europe, Asia, and parts of Western Australia. It will begin at 2:01 p.m. EDT (1801 GMT) on Oct. 28 and you can watch the action unfold live here on Space.com beginning at 3 p.m. EDT (1900 GMT). Our guide to what time the Oct. 28 lunar eclipse occurs has more details on when to look up.

According to In the Sky, observers in New York City will see the Hunter's Full Moon rise around 5:19 p.m. local time, with the sun setting at 5:53 p.m. Little ghosts and goblins will then enjoy the full moon's light until it sets at 08:14 EDT the following day. This Hunter's Moon will be particularly special, as it will be subject to a partial lunar eclipse, with the moon appearing as if a bite has been taken out of it.

Related: Watch the Full Hunter's Moon lunar eclipse with these free livestreams

See the moon up close! We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Look out for bright Jupiter shining close enough to the moon to share the same view in a pair of binoculars.

Following the Hunter's Moon, the illuminated face of the moon will begin to recede, progress astronomers call waning, heading to the completely dark new moon on Monday, Nov. 13. This will also signal the start of a new 29.5-day lunar cycle.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The name for October's full moon, the Hunter's Moon, can be traced back to the early 1700s, according to Farmer's Almanac. It refers to hunting deer, turkey, pheasants, and other game animals in mid to late Autumn that have spent summer gorging on abundant food.

Though the Hunter's Moon is the most common name for the October full moon in the Northern Hemisphere, there are alternative names connected to hunting such as the Pagan and English Medieval names, the "Sanguine Moon," or the "Blood Moon."

The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call it Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon — the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America use Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

Related: Full moon names for 2023 (and how they came to be)

The frosty lunar monikers will continue into November with next month's full moon, which falls on Nov. 27, commonly called the Beaver Moon but given the alternative names "Moon of Much White Frost On Grass" from the Algonquin and the "Frost Moon" in the language of the Assiniboine Nation.

If you are hoping to catch a look at the Hunter's Moon, our guides to the best telescopes and binoculars are a great place to start.

If you're looking to snap photos of the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph meteor showers, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of the Hunter's Moon and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.