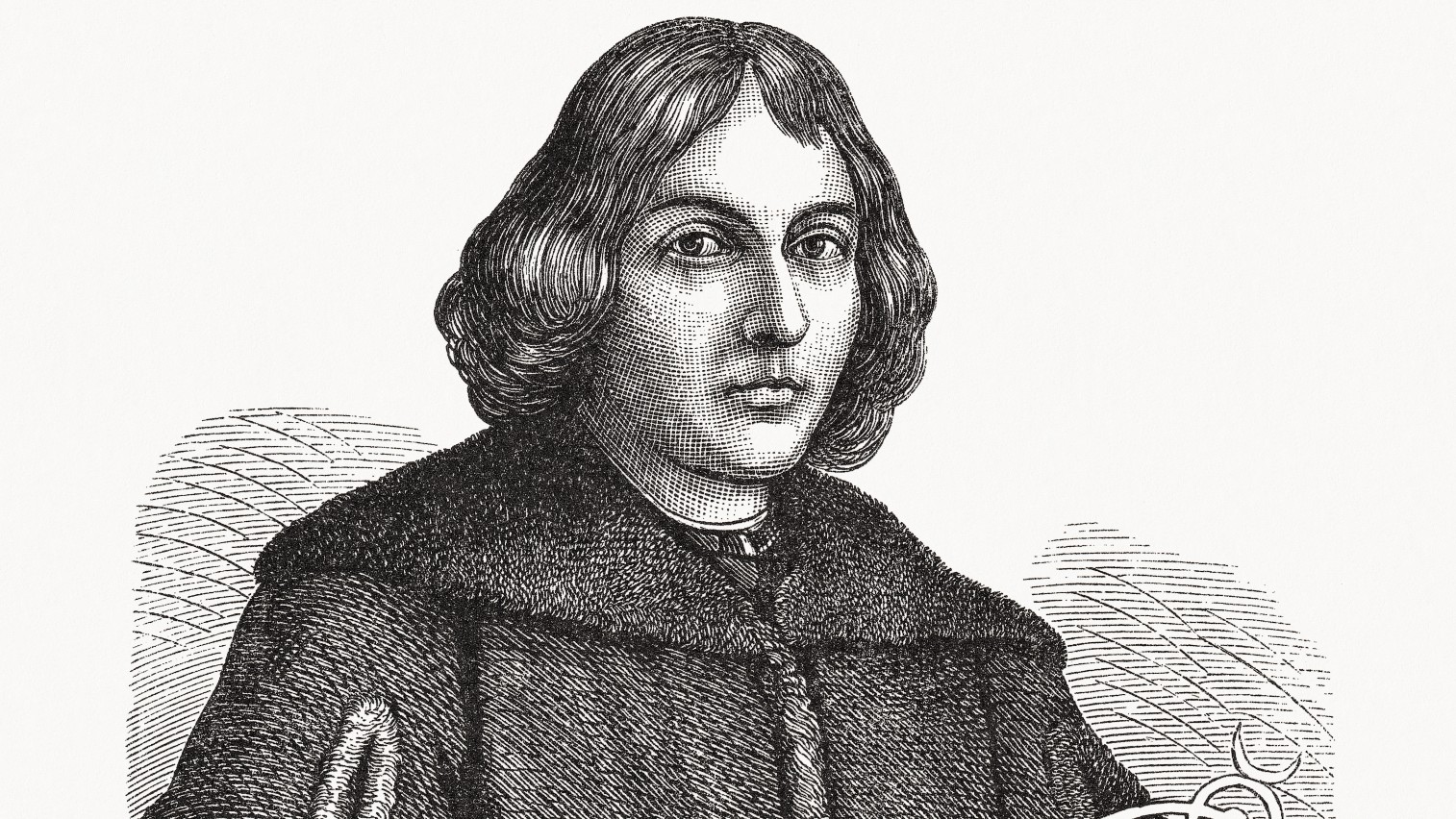

Nicolaus Copernicus biography: Facts & discoveries

Meet Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus.

Nicolaus Copernicus proposed his theory that the planets revolved around the sun in the 1500s, when most people believed that Earth was the center of the universe. Although his model wasn't completely correct, it formed a strong foundation for future scientists, such as Galileo, to build on and improve humanity's understanding of the motion of heavenly bodies.

Indeed, other astronomers built on Copernicus' work and proved that our planet is just one world orbiting one star in a vast cosmos loaded with both, and that we're far from the center of anything.

Countdown: The most famous astronomers of all time

Education

Born on Feb. 19, 1473, in Toruń, Poland, Mikolaj Kopernik (Copernicus is the Latinized form of his name) traveled to Italy to attend college, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Copernicus' father had died when the child was young, and his uncle became a leading figure in his life.

Copernicus' uncle wanted him to study the laws and regulations of the Catholic Church then return home to become a canon, a type of official in the Catholic Church.

However, while visiting several academic institutions, Copernicus spent most of his time studying mathematics and astronomy. While attending the University of Bologna, Copernicus lived and worked with astronomy professor Domenico Maria de Novara, doing research and helping him make observations of the heavens.

Due to his uncle's influence, Copernicus did become a canon in Warmia, in northern Poland, although he never took orders as a priest. He conducted his astronomical research in between his duties as canon, the Encyclopedia Britannica noted.

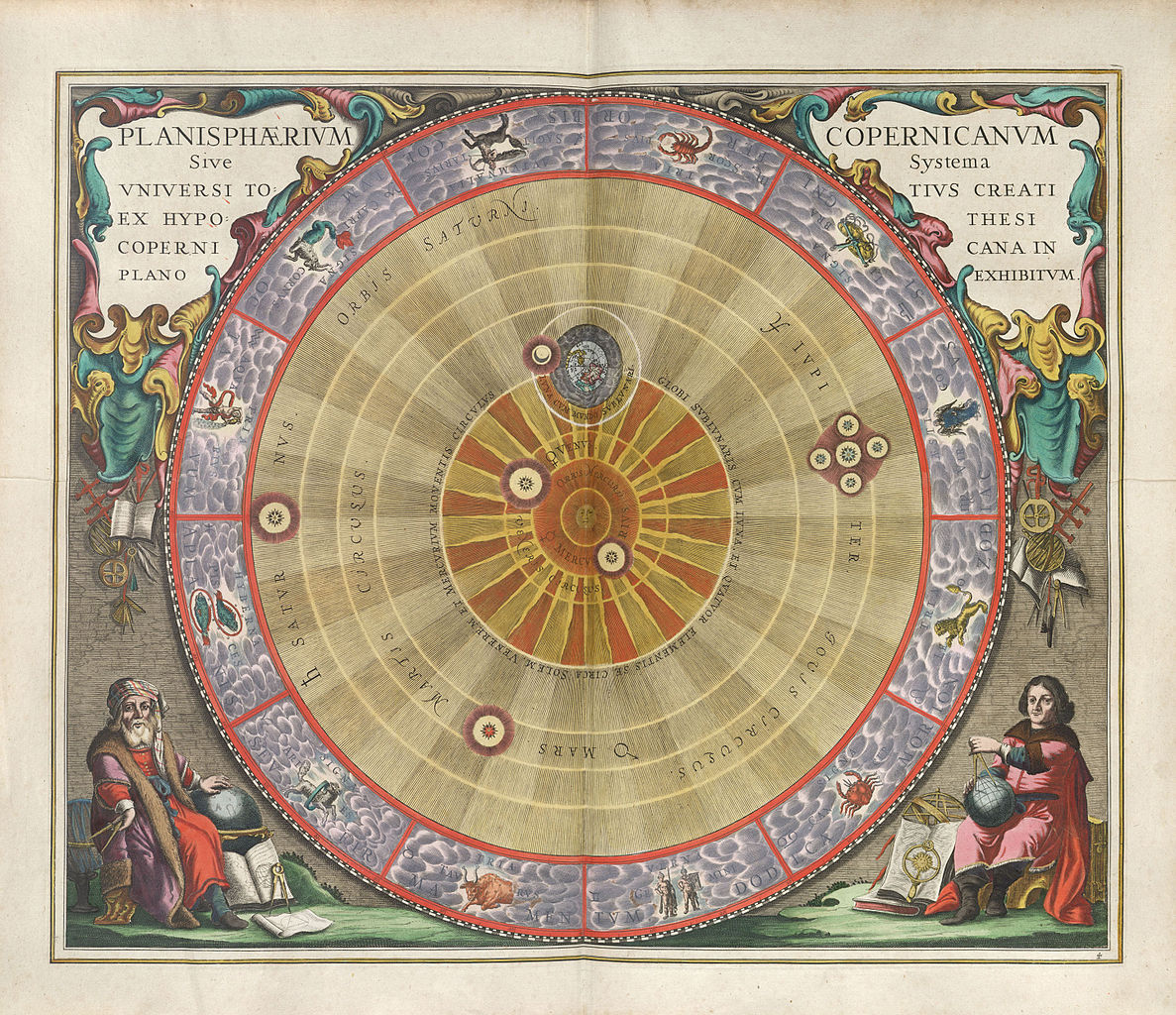

The Copernican model of the solar system

In Copernicus' lifetime, most believed that Earth held its place at the center of the universe. The sun, the stars, and all of the planets revolved around it.

One of the glaring mathematical problems with this model was that the planets, on occasion, would travel backward across the sky over several nights of observation. Astronomers called this retrograde motion. To account for it, the current model, based on the Greek astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy's view, incorporated a number of circles within circles — epicycles — inside of a planet's path. Some planets required as many as seven circles, creating a cumbersome model many felt was too complicated to have naturally occurred.

In 1514, Copernicus distributed a handwritten book to his friends that set out his view of the universe. In it, he proposed that the center of the universe was not Earth, but that the sun lay near it. He also suggested that Earth's rotation accounted for the rise and setting of the sun, the movement of the stars, and that the cycle of seasons was caused by Earth's revolutions around it.

Finally, he (correctly) proposed that Earth's motion through space caused the retrograde motion of the planets across the night sky (planets sometimes move in the same directions as stars, slowly across the sky from night to night, but sometimes they move in the opposite, or retrograde, direction).

Copernicus finished the first manuscript of his book, "De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium" ("On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres") in 1532. In it, Copernicus established that the planets orbited the sun rather than the Earth. He laid out his model of the solar system and the path of the planets.

He didn't publish the book, however, until 1543, just two months before he died. He diplomatically dedicated the book to Pope Paul III. The church did not immediately condemn the book as heretical, perhaps because the printer added a note that said even though the book's theory was unusual, if it helped astronomers with their calculations, it didn't matter if it wasn't really true. It probably also helped that the subject was so difficult that only highly educated people could understand it. The Church did eventually ban the book in 1616, according to Physics Today.

The Catholic Church wasn't the only Christian faith to reject Copernicus' idea.

"When 'De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium' was published in 1543, religious leader Martin Luther voiced his opposition to the heliocentric solar system model," says Biography.com. "His underling, Lutheran minister Andreas Osiander, quickly followed suit, saying of Copernicus, 'This fool wants to turn the whole art of astronomy upside down.'"

Copernicus died on May 24, 1543, of a stroke. He was 70.

Where was Copernicus buried?

In 2008, researchers announced that a skull found in Frombork Cathedral did belong to the astronomer, according to The Guardian. By matching DNA from the skull to hairs found in books once owned by Copernicus, the scientists confirmed the identity of the astronomer. Polish police then used the skull to reconstruct how its owner might have looked.

Nature quotes the AFP as stating that the reconstruction "bore a striking resemblance to portraits of the young Copernicus."

In 2010, his remains were blessed with holy water by some of Poland's highest-ranking clerics before being reburied, his grave marked with a black granite tombstone decorated with a model of the solar system. The tomb marks both his scientific contribution and his service as church canon.

"Today's funeral has symbolic value in that it is a gesture of reconciliation between science and faith," Jacek Jezierski, a local bishop who encouraged the search for Copernicus, said according to the Associated Press. "Science and faith can be reconciled."

The unmarked grave was not linked to suspicions of heresy, as his ideas were only just being discussed and had yet to be forcefully condemned, according to Jack Repcheck, author of "Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution Began."

"Why was he just buried along with everyone else, like every other canon in Frombork?" Repcheck said. "Because at the time of his death he was just any other canon in Frombork. He was not the iconic hero that he has become."

Refining the work of Copernicus

Although Copernicus' model changed the layout of the universe, it still had its faults. For one thing, Copernicus held to the classical idea that the planets traveled in perfect circles. It wasn't until the 1600s that Johannes Kepler proposed the orbits were instead ellipses. As such, Copernicus' model featured the same epicycles that marred Ptolemy's work, although there were fewer.

Copernicus' ideas took nearly a hundred years to seriously take hold. When Galileo Galilei claimed in 1632 that Earth orbited the sun, building upon the Polish astronomer's work, he found himself under house arrest for committing heresy against the Catholic Church.

Despite this, the observations of the universe proved the two men correct in their understanding of the motion of celestial bodies. Today, we call the model of the solar system, in which the planets orbit the sun, a heliocentric or Copernican model.

"Sometimes Copernicus is honored as having substituted the old geocentric system with the new, heliocentric one, as having regarded the sun, instead of the Earth, as the unmoving center of the universe," Konrad Rudnicki, an astronomer and author of "The Cosmological Principles," wrote. "This view, while quite correct, does not render the actual significance of Copernicus's work."

According to Rudnicki, Copernicus went beyond simply creating a model of the solar system.

"All his work involved a new cosmological principle originated by him. It is today called the Genuine Copernican Cosmological Principle and says, 'The Universe as observed from any planet looks much the same,'" Rudnicki wrote.

So while Copernicus' model physically placed the sun at the center of the solar system, it also figuratively removed the focus from Earth, making it just another planet.

Additional resources

You can read the English translation of Copernicus' manuscript "De Revolutionibus Orbium Cœlestium" here. Check out the complete works of Nicholas Copernicus Complete in "On the Revolutions: Nicholas Copernicus Complete Works (Foundations of Natural History)". Also, discover the many artefacts at the British Museum regarding Nicolaus Copernicus, here.

Bibliography

Jack Repcheck, "Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution Began," Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Sheila Rabin, "Nicolaus Copernicus," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2019.

Fred Hoyle, "The work of Nicolaus Copernicus," Proceedings of the Royal Society A, Volume 336, January 1974, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1974.0009.

Teresa Zielinska, "Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543)," Distinguished Figures in Mechanism and Machine Science, History of Mechanism and Machine Science Volume 1, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6366-4_5

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd