Scientists study plasma 'bubbles' in Earth's magnetic field with Gamera model named for Japanese monster

Ripples in the underbelly of the magnetosphere move like a plucked guitar string that quickly returns to equilibrium, one researcher said.

Auroras and satellite function might be influenced by ''bubbles'' of plasma near the tail of Earth's magnetosphere, researchers find.

The sun continuously emits what is known as "the solar wind," a stellar breeze that can travel 1 million mph (400 kilometers per second) through space. On Dec.15, 2019, researchers published a new study that investigated the vibrations and "bubbles" that the solar wind creates within Earth's magnetically charged shell, and how it shows up on Earth's night side.

Upon reaching Earth, the solar wind strikes the planet's magnetosphere. On the outer part of the magnetosphere, the solar wind's charged particles generally glide off like water on a duck's back; but in the inner magnetosphere, it causes turbulence, according to these researchers in a recent statement.

Related: Rising 'Phoenix' aurora and starburst galaxies light up the skies

This turbulence creates complex effects, including many different types of waves. For this study, physicists at Rice University developed a new method to study the disturbances, or oscillations, that occur in the plasma at the base of the magnetosphere..

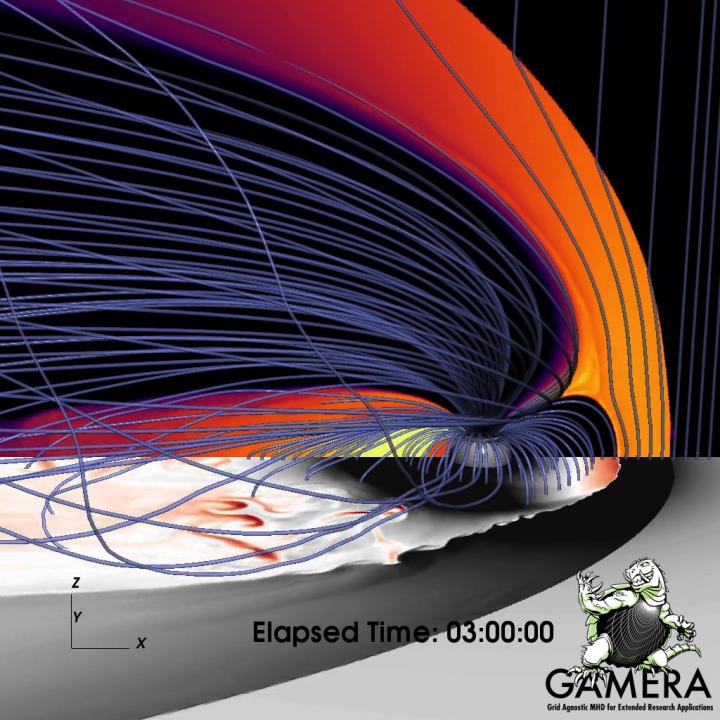

The Rice University physicists collaborated with researchers at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University to develop a code to help them run simulations about these oscillations, or "ripples." An algorithm known as the Rice Convection Model, which Rice officials say is "decades in the making," played a part in this magnetospheric code. The algorithm is called Gamera after the fictional Japanese monster of the same name.

Earth's magnetosphere is shaped a bit like the cross section of a wing. The side of the magnetosphere facing away from the sun — Earth's nightside — is where you have the pointed tail of the wing and where "burst bubbles" of plasma get caught and sink back toward Earth, creating ripples within the plasma.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The ripples move like a plucked guitar string that quickly returns to equilibrium, Frank Toffoletto, space plasma physicist at Rice University and lead author of the new study, said in the statement.

These low-frequency waves, called eigenmodes, haven't been studied much but "appear to be associated with dynamic disruptions to the magnetosphere" that cause phenomena like beautiful auroras, or less-appealing events, like disruptions to satellites and power grids here on Earth.

This new research was published on Dec. 15 in the journal JGR Space Physics.

- Bright Green Aurora Bird Takes Flight with a Running Rabbit Over Iceland (Photo)

- Here's Why Auroras on Earth Are Different in the North and South

- See Saturn's Stunning Auroras Glow Over Time in These Hubble Photos

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.