Gemini South Telescope in Chile to run solely on clean energy by 2027

Reducing air travel, installing solar panels and utilizing electric vehicles are just some of the ways NOIRLab aims on greatly reducing its carbon footprint.

NOIRLab, a federally-funded U.S. facility that operates a handful of large ground-based observatories in Arizona, Chile and Hawaii, made a major announcement on Monday (Nov. 27) regarding its clean energy goals. According to officials with the organization, it is on track to halve all planet-warming carbon emissions associated with its operations by the end of 2027. This would be the consequence of NOIRLab making changes to its infrastructure and reducing staff air travel.

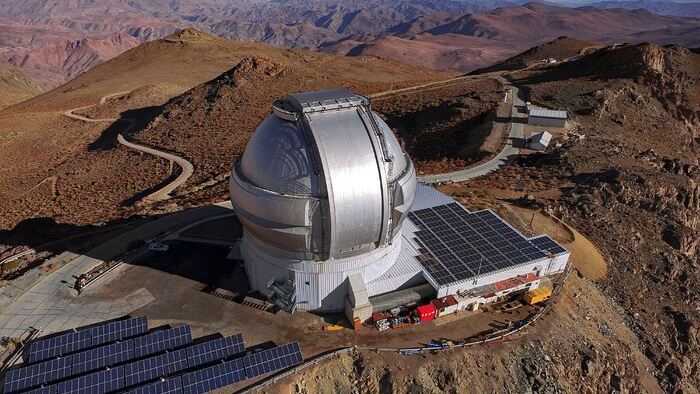

More specifically, new funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will be used to install solar panels and batteries at the Gemini South Telescope in Chile, which makes up one half of the International Gemini Observatory managed by NOIRLab. The upcoming changes will see the telescope run solely on renewable energy by 2027, according to a statement by the organization. Solar panels that already surround the telescope currently provide about 28 percent of its power.

Large astronomy observatories pump over a million tons of carbon dioxide into our atmosphere every year, a study found in 2022. Big, powerful telescopes, including those launched into space like the James Webb Space Telescope, demand large, capable machines called supercomputers to process enormous amounts of their data, build large-scale cosmological simulations — and more. But supercomputers, in turn, depend on large amounts of energy for power and also generate significant heat, both of which contribute to global warming.

Related: Hackers shut down 2 of the world's most advanced telescopes

The 2022 study also found that significant carbon emissions are generated from not just operating large telescopes, but also during their construction and manufacturing phases.

At NOIRLab, in addition to getting the Gemini South telescope to zero carbon emissions in the next few years, upcoming infrastructure changes at the organization are expected to cover 60 percent of the electricity necessary to run the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory when it is ready for its 2025 debut.

All in all, NOIRLab's annual carbon footprint will be reduced by about 2900 tons of carbon dioxide, which is "comparable to the annual electricity consumption of about 500 typical U.S. houses," the organization said in the same statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The goal, however, is to shrink NORLab's carbon footprint before the end of 2027 by about 6,200 tons of carbon dioxide emissions, the equivalent to the yearly electricity consumption of about 1,250 U.S. houses, the organization said.

To reach that ultimate goal, NOIRLab is replacing old heating, upgrading ventilation and air conditioning systems in its Arizona headquarters. The group also imagines shifting from gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles to electric ones across all of its facilities, starting with employing eight vehicles in the coming few years.

Plus, other than greenhouse gas emissions produced from supercomputing, recent attention has focused on how air travel impacts the human-driven climate crisis, and flying for conferences and other academic activities is a prevalent activity for astronomers. Any funding freed up at NOIRLab from reducing staff air travel by half will be "used to install energy-efficient equipment and solar panels across the facilities," the statement reads.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.