The Geminid meteor shower, which will likely be the very best meteor display of the year, is just around the corner, predicted peak late on Sunday night (Dec. 13).

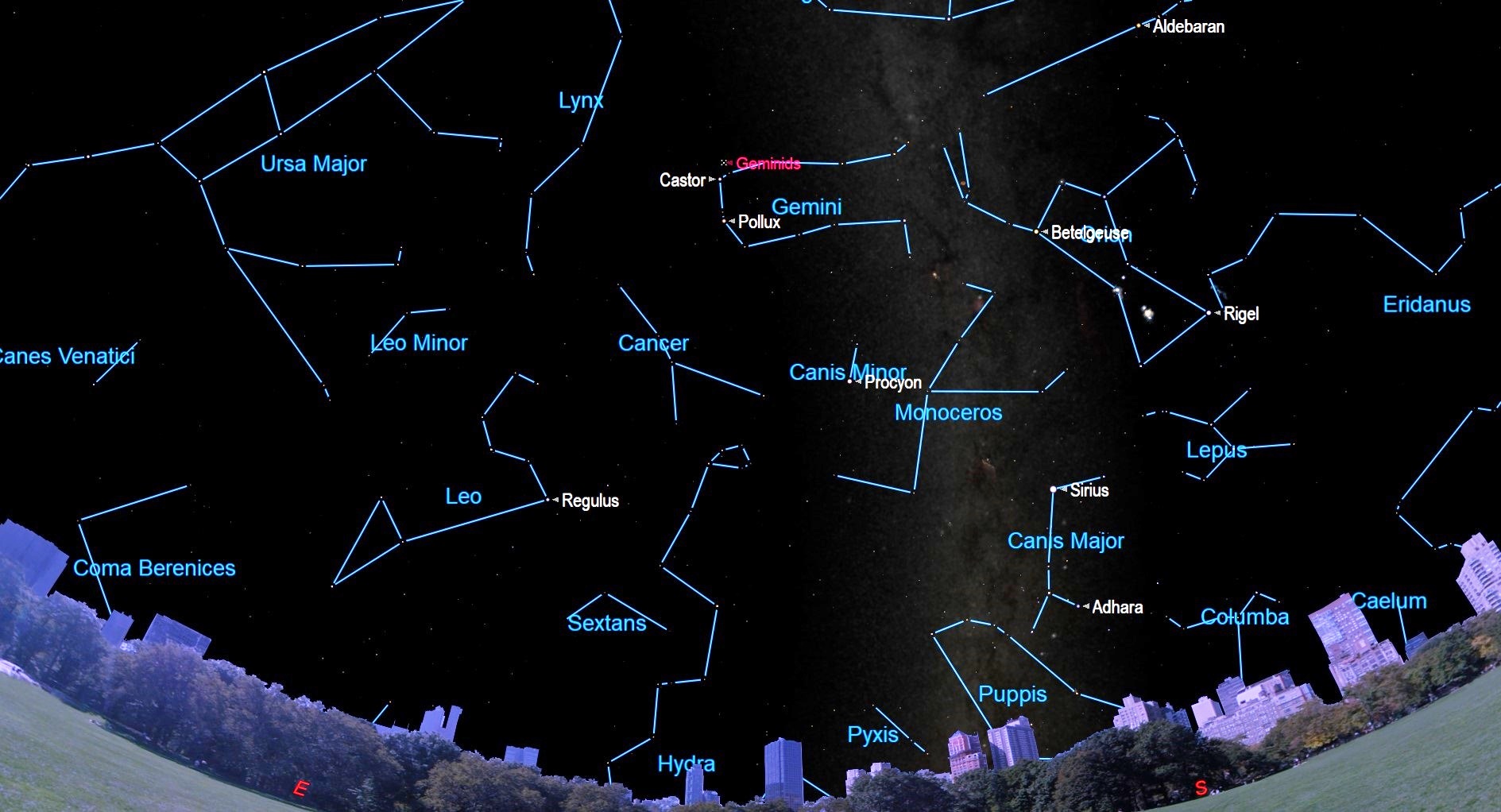

The Geminids get their name from the constellation of Gemini, the Twins. On the night of this shower's maximum, the meteors will appear to emanate from a spot in the sky near the bright star Castor, one of two stars marking one of the heads of the twin brothers (the other being Pollux).

The Geminid meteors are the most satisfying of all the annual showers, now even surpassing the famous Perseids of August. The Geminids are also "the new kids on the block" so far as the principal meteor showers are concerned. Practically all of the other meteor displays have histories dating back many hundreds or even thousands of years. The first anecdotal account of the Leonids dates back to 902 A.D. The Perseids have been recorded since 36 A.D., and April's Lyrids are the oldest of all, having first been recorded in Chinese chronicles as far back as 687 B.C.!

Related: Geminid meteor shower 2020: When, where & how to see it

But the first accounts of the Geminids are relatively recent; a scant few were seen in December 1862. The "shooting stars" have appeared every year since, gradually becoming more numerous and brighter.

Like scurrying field mice

Studies of past displays show that this shower has a reputation for being rich both in slow, bright, graceful meteors and fireballs as well as in faint meteors, with relatively fewer objects of medium brightness.

Geminids typically encounter Earth at 22 miles per second (that's about 79,200 mph, or 127,500 kph); roughly half the speed of a Leonid or Perseid meteor. Whereas a Leonid or Perseid can streak across your line of sight in a heartbeat, a typical Geminid might take a few seconds. I've often called them "celestial field mice," because they appear to scurry from one part of the sky to another. Many appear yellowish in hue, but a few can take on other colors: red, orange, blue, even green. Some even appear to form jagged or divided paths.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Earth moves quickly through this meteor stream producing a somewhat broad, lopsided activity profile. Rates increase steadily for two or three days before maximum, reaching roughly above a quarter of its peak strength two nights before maximum, and half of strong the night before maximum.

But after maximum comes a sharp drop-off; one-quarter peak strength the very next night. Late Geminids, however, tend to be especially bright. Renegade forerunners might be seen for a week or more before maximum, but the shower will be all but gone by the Dec. 16.

An outstanding Geminid year!

The Geminids perform excellently in any year, but without a doubt 2020 will be a superb year. Last year's display was seriously compromised by bright moonlight when a gibbous moon came up over the horizon during the evening hours and washed out many of the fainter Geminid streaks.

But this year, the moon will be in its new moon phase on Dec. 14, ensuring that the sky will be dark and moonless through the Geminids' peak night, making for perfect viewing conditions for the shower.

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in 2020's "Observer's Handbook" of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the Geminids are predicted to reach peak activity at 8 p.m. EST on Dec. 13 (0100 GMT on Dec. 14). That timing means Europe and North Africa east to central Russia and China are in the best positions to catch the very crest of the shower, when the rates could exceed 120 meteors per hour.

But for some 6 to 10 hours around the maximum rate, the meteors will remain very plentiful, so other places including North America should enjoy some very fine Geminid activity as well. Indeed, under normal conditions on the night of maximum activity, with ideal dark-sky conditions, at least 60 to 120 Geminid meteors can be expected to burst across the sky every hour on the average.

A critical observer's clause

However, here is a very important disclaimer: the actual number of meteors that you'll see hinges on two things.

- The light pollution at your observing site.

- The amount of the sky that you can see.

If you live in a rural location with few or no bright lights, you'll see lots of faint stars and lots of meteors. But if you live in a brightly-lit suburb or a large metropolitan area, the number of "shooting stars" that you will see will be considerably smaller. And if you observe from a location surrounded by tall trees or buildings, that too will cut into the number of Geminids you will see.

So, for the optimum views, get as far as possible from the light pollution of big cities and large towns and try to get to a place with a wide-open view of the night sky.

Generally speaking, depending on your location, Gemini begins to come up above the east-northeast horizon right as evening twilight is ending. So, you might catch sight of a few early Geminids as soon as the sky gets dark.

There is also a small chance of catching sight of some "Earth-grazing" meteors. Earthgrazers are long, bright shooting stars that streak overhead from a point near or even just below the horizon. Such meteors are distinctive because they follow long paths nearly parallel to our atmosphere.

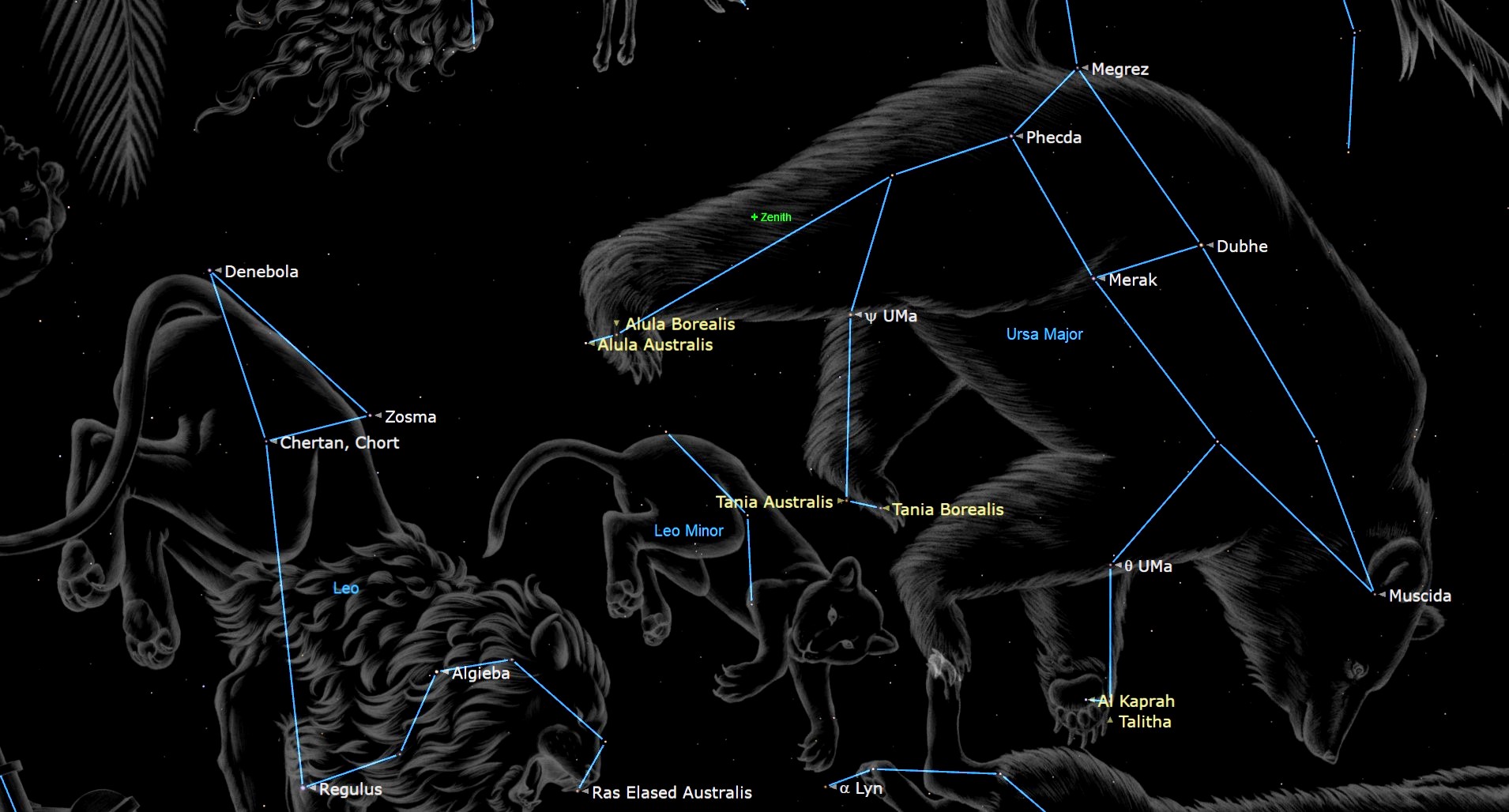

I recommend keeping your eyes moving around: rather than staring at any one place, look all over. Pretty soon you'll catch sight of your first meteor and mentally trace its path backwards. Soon a second will come by; trace that one backward also and take note of the general pattern of stars from where these two emanated from. A third one will come by and hopefully intersect in the same region of the sky as the first two did. That region will be the constellation Gemini, where the "radiation point," or radiant, of the meteors will be.

The Geminids begin to appear noticeably more numerous in the hours after 9 p.m. local time, because the shower's radiant is already fairly high in the eastern sky by then. The best views, however, come around 2 a.m., when their radiant will be passing nearly overhead. The higher a shower's radiant, the more meteors it produces all over the sky. Any meteor that you see that does not originate from that part of the sky is a sporadic and does not belong to the Geminid stream.

A chilly undertaking

Keep this in mind: at this time of year, meteor watching can be a long, cold business. You wait and you wait for meteors to appear, and they don't appear right away. If you're cold and uncomfortable, you're not going to be looking for meteors for very long!

So, if you do plan to be outside for a long period of time on these frosty, cold nights, remember that enjoying the starry winter sky requires protection against the low temperatures. This was a bitter lesson that the very first director of New York's Hayden Planetarium, Dr. Clyde Fisher, learned one night in 1931, when he and noted meteor expert Professor Charles Olivier journeyed to the Catskill Mountains to do some meteor observing. It was on a night where "the air bit shrewdly," yet Dr. Fisher only wore silk socks and an overcoat, and was soon doing a tap dance to keep his feet from freezing.

One of the best garments I have found is a hooded ski parka, which is lightweight yet excellent insulation, and ski pants that are warmer than ordinary trousers. And, as Dr. Fisher would certainly attest, it is also important to remember your feet! While two pairs of warm socks in loose-fitting shoes are often adequate, for protracted observing on bitter-cold nights wear insulated boots.

And avoid craning your head to look skyward. If you do that for an hour or more, you almost certainly will awaken the following morning with a stiff neck or achy shoulders. The best piece of equipment you can use for meteor observing is a long beach or lounge chair to stretch out and stay comfortable. If it's exceptionally cold, wrap yourself up in a blanket.

Give your eyes time to adapt to the dark before starting.

Hot cocoa or coffee can take the edge off the chill, as well as provide a slight stimulus. But stay away from alcohol! It can cause mental confusion, difficulty in remaining conscious, and dulled responses.

So good luck and clear skies to all … but remember to stay warm!

Editor's note: If you happen to observe the Geminid meteor shower of 2020 and would like to share the experience with Space.com for a story or slideshow, send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.