The planet is dying faster than we thought

A triple-threat of climate change, biodiversity loss and overpopulation is bearing down on Earth.

Humanity is barreling toward a "ghastly future" of mass extinctions, health crises and constant climate-induced disruptions to society — one that can only be prevented if world leaders start taking environmental threats seriously, scientists warn in a new paper published Jan. 13 in the journal Frontiers in Conservation Science.

In the paper, a team of 17 researchers based in the United States, Mexico and Australia describes three major crises facing life on Earth: climate disruption, biodiversity decline and human overconsumption and overpopulation. Citing more than 150 studies, the team argues that these three crises — which are poised only to escalate in the coming decades — put Earth in a more precarious position than most people realize, and could even jeopardize the human race.

The point of the new paper isn't to scold average citizens or warn that all is lost, the authors wrote — but rather, to plainly describe the threats facing our planet so that people (and hopefully political leaders) start taking them seriously and planning mitigating actions, before it's too late.

Related: US could reach 'net-zero' carbon by 2050. Here’s how.

"Ours is not a call to surrender," the authors wrote in their paper. "We aim to provide leaders with a realistic 'cold shower' of the state of the planet that is essential for planning to avoid a ghastly future."

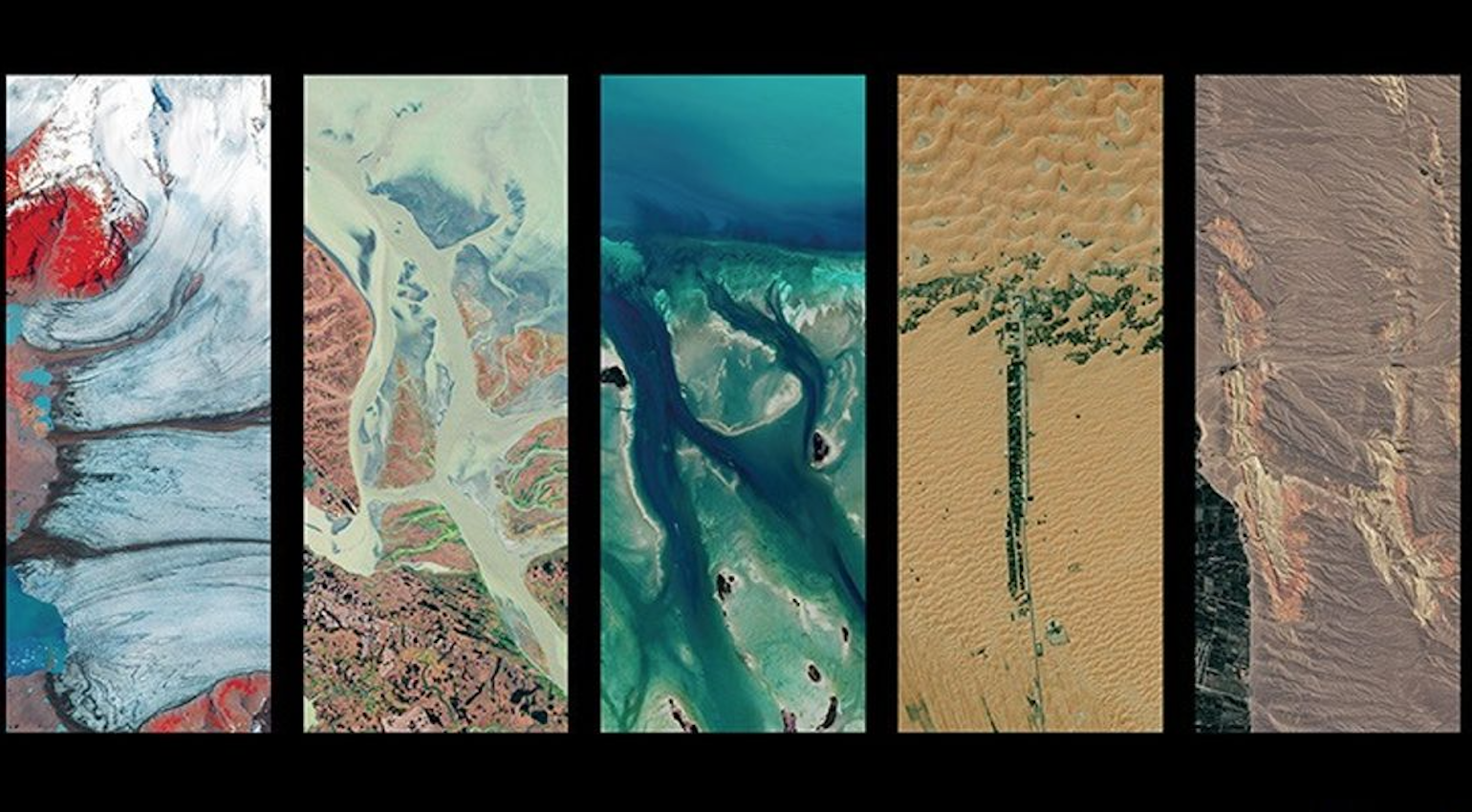

What will that future look like? For starters, the team writes, nature will be a lot lonelier. Since the start of agriculture 11,000 years ago, Earth has lost an estimated 50% of its terrestrial plants and roughly 20% of its animal biodiversity, the authors said, citing two studies, one from 2018 and the other from 2019. If current trends continue, as many as 1 million of Earth's 7 million to 10 million plant and animal species could face extinction in the near future, according to the new paper.

Such an enormous loss of biodiversity would also disrupt every major ecosystem on the planet, the team wrote, with fewer insects to pollinate plants, fewer plants to filter the air, water and soil, and fewer forests to protect human settlements from floods and other natural disasters, the team wrote.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Meanwhile, those same phenomena that cause natural disasters are all predicted to become stronger and more frequent due to global climate change. These disasters, coupled with climate-induced droughts and sea-level rise, could mean 1 billion people would become climate refugees by the year 2050, forcing mass migrations that further endanger human lives and disrupt society.

Overpopulation will not make anything easier.

"By 2050, the world population will likely grow to ~9.9 billion, with growth projected by many to continue until well into the next century," the study authors wrote.

This booming growth will exacerbate societal problems like food insecurity, housing insecurity, joblessness, overcrowding and inequality. Larger populations also increase the chances of pandemics, the team wrote; as humans encroach ever farther into wild spaces, the risk of uncovering deadly new zoonotic diseases — like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 — becomes ever greater, according to a study published in September 2020 in the journal World Development.

While we can see and feel the effects of global warming on a daily basis — like record-setting heat across the world and increasingly active hurricane seasons, for instance — the worst effects of these other crises could take decades to become apparent, the team wrote. That delay between cause and effect may be responsible for what the authors call an "utterly inadequate" effort to address these encroaching environmental threats.

"If most of the world's population truly understood and appreciated the magnitude of the crises we summarize here, and the inevitability of worsening conditions, one could logically expect positive changes in politics and policies to match the gravity of the existential threats," the team wrote. "But the opposite is unfolding."

Indeed, just last week a study published in the journal Nature Climate Change revealed that humans have already blown past the global warming targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement, and we are currently on track to inhabit a world that is 4.1 degrees Fahrenheit (2.3 degrees Celsius) warmer than average global temperatures in the pre-industrial era — slightly more than halfway to the United Nation's "worst-case scenario." Nations have similarly failed to meet basic biodiversity targets set by the U.N. in 2010, the authors note.

The dark future described in this paper is not guaranteed, the authors wrote, so long as world leaders and policymakers start immediately taking the problems before us seriously. Once leaders accept "the gravity of the situation," then the large-scale changes needed to conserve our planet can begin. Those changes must be sweeping, including "the abolition of perpetual economic growth … [and] a rapid exit from fossil-fuel use," the authors wrote.

But the first step is education.

"It is therefore incumbent on experts in any discipline that deals with the future of the biosphere and human well-being to … avoid sugar-coating the overwhelming challenges ahead and 'tell it like it is,'" the team concluded. "Anything else is misleading at best … potentially lethal for the human enterprise at worst."

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.